Old School: The Iliad

A while back it was time to hit the dreaded “To Be Read” pile, and I found myself in the mood for a good, old fashioned yarn full of blood and sweat and battles with edged weapons and feats of valor and derring-do, a tale of larger than life heroes and their mighty deeds — in other words, something old school. ( I had just finished reading a volume of John Updike short stories set in suburban, middle-class Pennsylvania, so I was ready, as John Cleese used to say, for something completely different.)

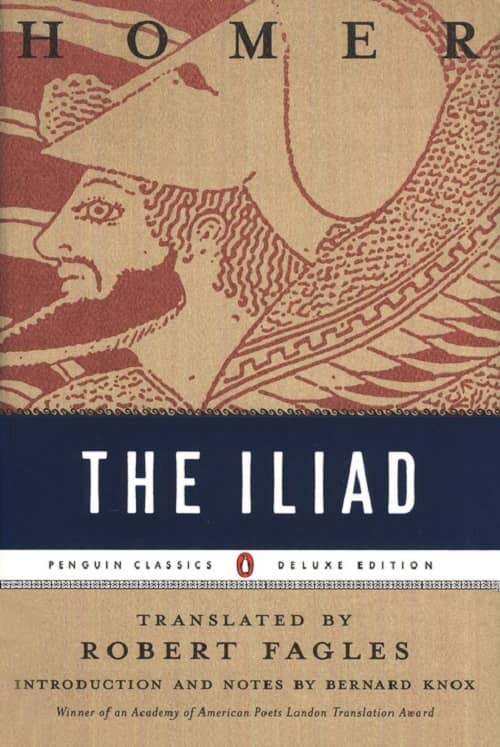

While not entirely eschewing the new, in my reading choices I do tend to lean toward older, more established books and authors (test of time and all that, you know — plus, they’re usually cheaper) and this time I decided to skew just about as far in that direction as it’s possible to skew. I reached all the way down to the bottom of the stack — three millennia down — and pulled up The Iliad. (At that moment, Western Civ teachers across the land contentedly smiled in their sleep without even knowing why.) Having “little Latin and less Greek” (as in none) I chose the highly regarded Robert Fagles translation, which has been laying around the house unread for the last, oh, twenty five years.

What follows is in no sense a learned reading of The Iliad (as will immediately be apparent!), but is simply this reader’s untutored reaction to his initial encounter with one of the world’s great books. It’s rather like a mayfly’s head-on meeting with a Mack truck; the insect’s reaction may not exactly be profound, but it has no doubt that it has been hit by something too big and serious to ignore.