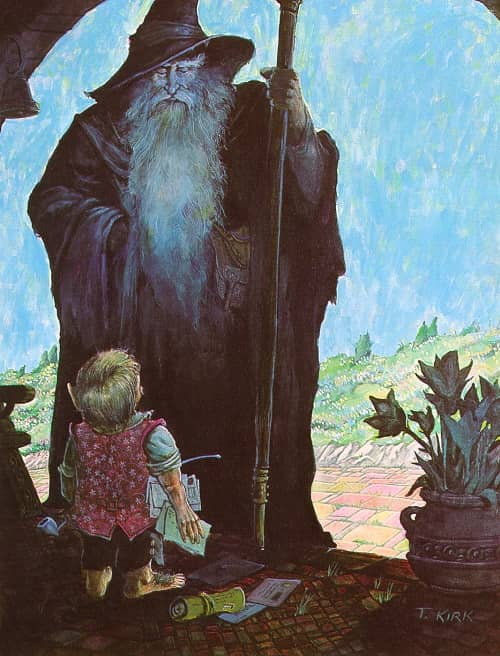

First Impressions: Tim Kirk’s 1975 Tolkien Calendar

Gandalf and Bilbo

How does the old saying go? “You never get a second chance to make a first impression.” It’s often true that the first encounter has an ineradicable effect, whether the meeting is with a person, a work of art, or a world. It’s certainly true in my case; I had my first and, in some ways, most decisive encounter with Middle-earth before I ever read a word of The Lord of the Rings. My first view of that magical place came through the paintings of Tim Kirk, in the 1975 J.R.R. Tolkien Calendar, and that gorgeous, pastel-colored vision of the Shire and its environs is the one that has stayed with me. Almost half a century later, Kirk’s interpretation still lies at the bottom of all my imaginings of Tolkien’s world.

There had been two Tolkien calendars before Kirk’s. The 1973 and 1974 editions used Tolkien’s own illustrations, some of the same ones that Ballantine (which also published the calendars) used on the covers of the “authorized” paperback editions of the novels, the ones that were carried around like books of Holy Writ in high schools and colleges during those years when fantasy felt like a secret and the news of what it was and what it could do had yet to spread very far.