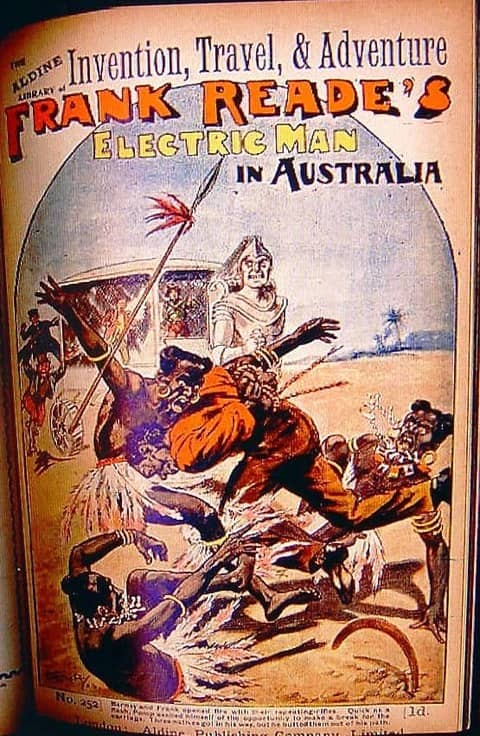

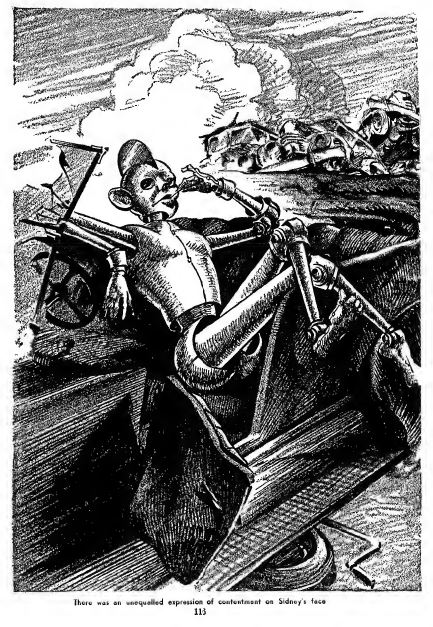

The Mighty Electric Men

“This man is a Samson in physical strength – in fact, the limit of his strength is unknown even to me., as every bone and muscle in him is of the finest steel. The machinery that works his limbs is inside of him, and he can walk, run, jump, and kick forward or backward with wonderful agility. The motive power that moves him is in a powerful electric battery enclosed in yonder box, under the floor of the carriage, and is communicated to him through wires inside the shafts. … By pressing one knob inside the carriage, there, I start the battery under the floor, and the man shows signs of light and life. That globe inside the helmet gives forth a light that equals the noonday sun, and his eyes do the same. At will I can extinguish all the lights, or only one at a time, just as I may elect. Then another knob starts him going, and another will turn him to the right and another to the left – just as a faithful horse obeys the rein and the bit – and all, too, without my being exposed to any danger from without.”

We think of robots being fairly modern marvels, but that’s definitely a description of a robot and it dates to October 10, 1886. The Electric Man in Australia (the fantastically racist cover is from a later London magazine reprint, and yes, those are supposed to be Australian aborigines) was the invention of Frank Reade, Jr., a young inventor who was the prototype for Tom Swift and all his ilk. The adventures of young Frank – there had been a Frank Sr. for four books, with Harry Enton disguised as “Noname” – were written by the amazingly prolific “Noname,” really Luis Senarens, himself a teenager when the first Frank Reade, Jr. book, Frank Reade Jr. and His Steam Wonder, appeared in 1882 in Frank Tousey’s Boys Weekly. A “boys weekly” became a generic term for 8, 16, or 32 page weekly newsprint magazines. For a nickel, later a dime, readers got an exciting illustration on the front page, with the others crammed full of tiny type adventure or mystery novels or stories, sometimes serialized, sometimes filling an entire issue. Dozens of them appeared in the late 19th century only to be superseded by the coming of the pulp magazines.