Black Static #26

Black Gate contributor Mark Rigney’s story, “The Demon Laplace,” inspires the cover art by Rik Rawling for the December 2011-January 2012 Black Static. A variation of the “be careful what you wish for” trope, Rigney’s protagonist, Alan, is a 27 year-old postal worker whose lackluster love life has him worrying that he’ll never find someone to settle down with or, worse, he’ll settle for whoever might come along. Then he meets mercurial Michael Wish (ostensibly short for Wyczniewski), a postal colleague of Alan’s who is taking a break from grad studies in statistics. Michael in Hebrew means “he who is like god” and who better than a god to grant wishes; unless, that is, the god is really a devil.

Black Gate contributor Mark Rigney’s story, “The Demon Laplace,” inspires the cover art by Rik Rawling for the December 2011-January 2012 Black Static. A variation of the “be careful what you wish for” trope, Rigney’s protagonist, Alan, is a 27 year-old postal worker whose lackluster love life has him worrying that he’ll never find someone to settle down with or, worse, he’ll settle for whoever might come along. Then he meets mercurial Michael Wish (ostensibly short for Wyczniewski), a postal colleague of Alan’s who is taking a break from grad studies in statistics. Michael in Hebrew means “he who is like god” and who better than a god to grant wishes; unless, that is, the god is really a devil.

Further complicating the picture is whether mathematics can actually predict future behavior (if you aren’t familiar with Laplace’s equation, Google can explain it for you). After a series of what could be clever parlor tricks, an initially dubious Alan comes to invest god-like powers in Michael when the prediction that Alan will marry the next woman he talks to comes true.

The question is does it come true because Michael actually can predict the future or is it because Alan is so thorough convinced of Michael’s prestidigitation that he acts to make it true? Knowing, or at least believing, that someone can foretell future events leads to Alan’s obsession with finding out what he should do next. Problem is, Michael disavows that he was really doing anything more than “messing” with Alan:

“You little jackass. You want what really happened. Fine. When we met, sorting mail? That was a break from grad school–statistics,yes, probability curves — but I was halfway through my thesis, I was bored stiff, and I needed some kind of inspiration. Turns out what I needed was a live. unsuspecting subject. And there you were, a walking tabula rosa, just going with the flow…You fell for everything I said, hook, line and sinker. There. Is that what you came to hear?

Problem is, that’s not what Alan came to hear. Which results in tragedy (you are reading a dark horror magazine so why would you expect anything less?) that may, or may not, have been easily foreseen.

Problem is, that’s not what Alan came to hear. Which results in tragedy (you are reading a dark horror magazine so why would you expect anything less?) that may, or may not, have been easily foreseen.

In your future I see some interesting reading ahead.

This month’s Apex Magazine features new fiction from Cat Rambo (“So Glad We Had This Time Together”) and Sarah Dalton (“Sweetheart Showdown”), as well as a reprint of “The Prowl” by Gregory Frost, who is also the featured interview. Stephan Segal provides the cover art and John Hines discusses “Writing About Rape.”

This month’s Apex Magazine features new fiction from Cat Rambo (“So Glad We Had This Time Together”) and Sarah Dalton (“Sweetheart Showdown”), as well as a reprint of “The Prowl” by Gregory Frost, who is also the featured interview. Stephan Segal provides the cover art and John Hines discusses “Writing About Rape.” This month’s Apex Magazine features

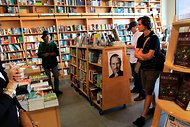

This month’s Apex Magazine features  So it would seem that the death of the physical book and the physical bookstore is greatly exaggerated.

So it would seem that the death of the physical book and the physical bookstore is greatly exaggerated.  The December issue of Clarkesworld is currently

The December issue of Clarkesworld is currently

The November

The November

The November issue of Clarkesworld is currently

The November issue of Clarkesworld is currently  The latest Apex Magazine is now

The latest Apex Magazine is now