Short Fiction Review #21 1/2: Intelligent (?) Design and the Godfall’s Chemsong by Jeremiah Tolbert

If there is a watch, then there must be a watchmaker. That’s the crux of the argument for intelligent design, that existence, and specifically you and me, are the result of some conscious creator. My main problem with this is the adjective “intelligent.” If I was designing existence, there’s a lot I’d leave out, like cancer or maggots or flatulence or Glenn Beck. Or that for certain kinds of life to continue and thrive, other life forms must suffer. Besides, this all begs the question of, if there is a designer (intelligent or otherwise), who created the designer?

If there is a watch, then there must be a watchmaker. That’s the crux of the argument for intelligent design, that existence, and specifically you and me, are the result of some conscious creator. My main problem with this is the adjective “intelligent.” If I was designing existence, there’s a lot I’d leave out, like cancer or maggots or flatulence or Glenn Beck. Or that for certain kinds of life to continue and thrive, other life forms must suffer. Besides, this all begs the question of, if there is a designer (intelligent or otherwise), who created the designer?

Whether our universe was a random cosmic accident, the result of some higher consciousness declaring, “Let there be light,” Olaf Stapledon’s “Starmaker,” or a computer simulacrum created by another dimension of beings with a lot of bandwidth, who knows? And whatever we come up with as an explanation, most likely it is wrong.

Why? Well, the answer is in the Bible, though it’s not the answer religious fundamentalists tend to appreciate. In the Book of Job, God has plagued his good and loyal servant with one catastrophe after another. Job petitions for explanation. But Job’s friends keep telling him the explanation is obvious: Job must have offended God. Job insists he hasn’t. God gets tired of listening to all this, and appears before them and asks if any one of them ever created a deer, or the arch of the heavens. No one here except, God, right? Then stop being arrogant and thinking you have any idea of what God does or why he does it. It’s beyond your limited comprehension. You guys haven’t got the faintest clue.

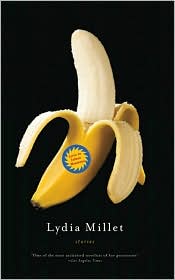

While her work sometimes hints at the fantastic, Lydia Millet isn’t strictly speaking a fantasy writer, certainly not in the sense of questing elves or weird alternate universes, and certainly not as evidenced in her new short story collection, Love in Infant Monkeys. Yet Millet’s work is frequently mentioned in genre venues; indeed, one of the stories collected here, “Thomas Edison and Vasil Golakov,” (in which the famed inventor of light bulbs and power generation attains metaphysical illumination by continually re-running a film of a circus elephant’s seemingly Christ-like electrocution)previously appeared in

While her work sometimes hints at the fantastic, Lydia Millet isn’t strictly speaking a fantasy writer, certainly not in the sense of questing elves or weird alternate universes, and certainly not as evidenced in her new short story collection, Love in Infant Monkeys. Yet Millet’s work is frequently mentioned in genre venues; indeed, one of the stories collected here, “Thomas Edison and Vasil Golakov,” (in which the famed inventor of light bulbs and power generation attains metaphysical illumination by continually re-running a film of a circus elephant’s seemingly Christ-like electrocution)previously appeared in  Very much looking forward to

Very much looking forward to

In the mail today, just in time for Halloween, is the blood-spattered graphic of the October/November

In the mail today, just in time for Halloween, is the blood-spattered graphic of the October/November cover of Black Static magazine, the horror and dark fantasy counterpart that alternates monthly appearances with Interzone science fiction published by the folks at

cover of Black Static magazine, the horror and dark fantasy counterpart that alternates monthly appearances with Interzone science fiction published by the folks at  For this edition of my irregular review of the latest (more or less) short fiction, I thought I’d try something a little different. Usually I try to focus on the stories that worked the most for me, with maybe some attention on those that didn’t and why; at the same time, I also try to convey a flavor of everything else, if only just to alert you that an author is in the publication without, for any number of reasons, wanting to get into discussing the story to any great length. Note the use of the word “try.” One of the challenges here is to provide some substantive, possibly even useful, discussion to an audience that I’m assuming hasn’t already read the material. As

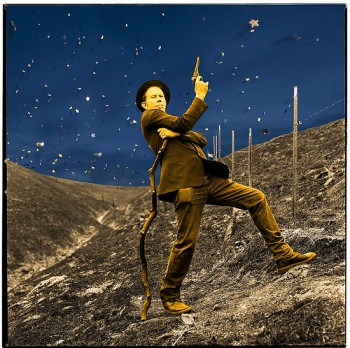

For this edition of my irregular review of the latest (more or less) short fiction, I thought I’d try something a little different. Usually I try to focus on the stories that worked the most for me, with maybe some attention on those that didn’t and why; at the same time, I also try to convey a flavor of everything else, if only just to alert you that an author is in the publication without, for any number of reasons, wanting to get into discussing the story to any great length. Note the use of the word “try.” One of the challenges here is to provide some substantive, possibly even useful, discussion to an audience that I’m assuming hasn’t already read the material. As  Fans of Tom Waits are often divided into two camps: those who favor the early boozy Kerouac, be-bop inspired crooner of life’s derelicts and losers up until he transmogrified beginning with the “Heartattack and Vine” album and “crossed over” into Kurt Weill cacaphonous orator of the absurd; fans of the later period sometimes disdain the earlier, and vice versa, despite the obvious connections. Me, I’m in the third camp as a huge admirer of both milieus. (I suppose there’s a further quarter of people who can’t stand Waits at all, but, much like the folks who still tiresomely maintain Dylan hasn’t done anything since his protest days, aren’t worth serious attention.)

Fans of Tom Waits are often divided into two camps: those who favor the early boozy Kerouac, be-bop inspired crooner of life’s derelicts and losers up until he transmogrified beginning with the “Heartattack and Vine” album and “crossed over” into Kurt Weill cacaphonous orator of the absurd; fans of the later period sometimes disdain the earlier, and vice versa, despite the obvious connections. Me, I’m in the third camp as a huge admirer of both milieus. (I suppose there’s a further quarter of people who can’t stand Waits at all, but, much like the folks who still tiresomely maintain Dylan hasn’t done anything since his protest days, aren’t worth serious attention.)