Birthday Reviews: Bruce McAllister’s “World of the Wars”

Bruce McAllister was born on October 17, 1946.

McAllister’s s novelette “Dream Baby” was nominated for the Nebula and Hugo Award in 1988. He was nominated for a second Hugo Award in 2007 for his short story “Kin.” His novelette “The Bleeding Child” (a.k.a. “The Crying Child”) earned him a nomination for the Shirley Jackson Award in 2013. He edited the anthology There Won’t Be War with Harry Harrison. He has collaborated on fiction with Barry N. Malzberg, Andreas Neumann, Patrick Smith, and W.S. Adams.

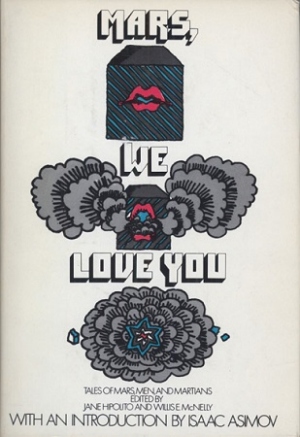

“World of the Wars” was originally published in Mars, We Love You: Tales of Mars, Men, and Martians, edited by Jane Hipolito and Willis E. McNelly in 1971. The book has also been published as The Book of Mars. The only other time the story has been reprinted was in McAllister’s 2007 collection The Girl Who Loved Animals and Other Stories.

McAllister’s “World of the Wars” isn’t really a science fiction or even a fantasy story, but rather a story about how the promise of space travel can influence a young life. Timmothy Turner lives in a world in which smog has run rampant without the intervention of the EPA in the mid-70s. The night sky is invisible, but the young boy has heard stories about what is above the ever-lingering haze, most from his friend, Jimmy, who has read books set on Mars.

Timmothy wants nothing more than to see Mars and when he spots what may be a red light on a distant building, he is convinced that the distant planet has broken through the layers of pollution to speak to him and he forms a club with his friends, all of whom have to be able to see Mars in order to be allowed to join.