The Golden Age of Science Fiction: SF Commentary, edited by Bruce Gillespie

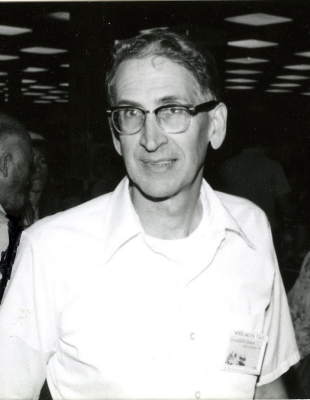

The Ditmar Awards are named for Australian fan Martin James Ditmar Jenssen. Founded in 1969 as an award to be given by the Australian National Convention, during a discussion about the name for the award, Jenssen offered to pay for the award if it were named the Ditmar. His name was accepted and he wound up paying for the award for more years than he had planned. Ditmar would eventually win the Ditmar Award for best fan artist twice, once in 2002 and again in 2010. The Australian Fanzine Award was one of the Ditmar’s original awards and the first one was won by John Bangsund for Australian SF Review. Bruce Gillespie won his first Ditmar for SF Commentary in 1972 and the ‘zine also won the award in 1973, 1977, 1980, 2002, and 2018. He also won the award in 1986 and 1999 for his ‘zine Metaphysical Review and in 2010 for Steam Engine Time. Rich Horton took a look at SF Commentary as the winner of the 1973 Ditmar Award in his companion series looking at his own Golden Age of Science Fiction.

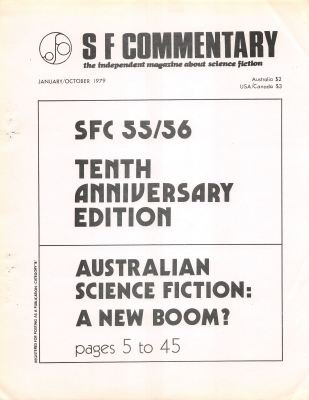

Bruce Gillespie began publishing SF Commentary in 1969 and by 1979 he was ready to publish issues 55 through 57, although the numbering a count was a little screwy. In January, he published a 68 page combination issue, numbered 55-56 and in November, he published the final issue of the year, 57, which came in at 16 pages.

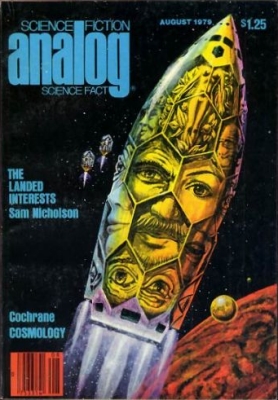

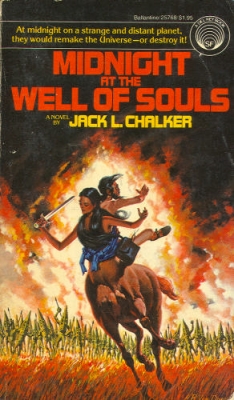

Combined issue 55/56 opens with an editorial by Gillespie extolling the ten years that he has been publishing the fanzine. The article traces the history of the fanzine, and through it Australian fandom, through the ten years of its existence, including the ill-fated attempt in 1976 to turn the ‘zine into a semi-professional magazine. Toward the end of the article, Gillespie turns his attention away from the zine and fandom and discusses the major events and publications in science fiction over the course of the decade, along with a lengthy bibliography of stories published during that time that he would recommend. The article provides a lengthy and full view of the world of science fiction, as seen from Australia, from 1969 through the beginning of 1979. Gillespie summation of the decade runs for about a third of the article.