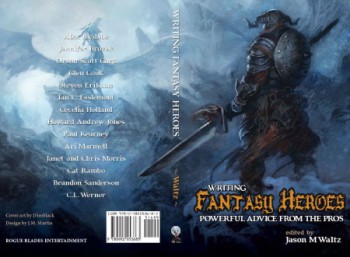

We’ve come to the last installment of my review of Writing Fantasy Heroes: Powerful Advice from the Pros. It’s a peculiar book, different in several ways I have talked about before from other books on writerly craft. It’s specialized by both genre and cluster of techniques, and each chapter shows a noted author using examples from his or her own work to demonstrate how to use a particular technique well (or, in the case of early drafts, badly, followed by advice on revision). Although the book is, by design, most useful for the newcomer to writing fantasy, it has something to offer more seasoned writers, and it’s of great value to teachers of writing who specialize in, or are at least willing to engage with, genre fiction.

Paul Kearney’s piece on large-scale battle scenes is just what I hoped it would be. You know all the familiar gripes about fantasy warfare that fails the suspension-of-disbelief test: the army never seems to eat or excrete, never needs to get paid, charges its horses directly into walls of seasoned enemy pikemen, and so on. “So You Want to Fight a War” addresses all those mundane things an author must get right if the fantasy elements of her story are to feel real to the reader, and then Kearney pushes past the gripes into solutions that any conscientious author can learn to implement. It’s that last bit that I found truly refreshing — many discussions of military verisimilitude get bogged down in griping. Kearney assumes throughout that it’s possible for his reader to get this stuff right, with enough good models, research, and practice.

Paul Kearney’s piece on large-scale battle scenes is just what I hoped it would be. You know all the familiar gripes about fantasy warfare that fails the suspension-of-disbelief test: the army never seems to eat or excrete, never needs to get paid, charges its horses directly into walls of seasoned enemy pikemen, and so on. “So You Want to Fight a War” addresses all those mundane things an author must get right if the fantasy elements of her story are to feel real to the reader, and then Kearney pushes past the gripes into solutions that any conscientious author can learn to implement. It’s that last bit that I found truly refreshing — many discussions of military verisimilitude get bogged down in griping. Kearney assumes throughout that it’s possible for his reader to get this stuff right, with enough good models, research, and practice.

As in Brandon Sanderson’s chapter on “Writing Cinematic Fight Scenes,” the reader is urged to map the combatants’ positions in space. Of course, with at least two armies’ worth of combatants, what one does with the map is a little more complicated this time around:

Keep the map beside you as you write, and as the narrative progresses and the lines move and break and reform, annotate your map. By the end of the battle it should be covered in scrawls, but you will still see the sense within it. It should also have a scale, so that if you want one character to see another across that deadly space, you can gauge whether it’s possible or not. Battlefields can be large places, miles wide. Our ten thousand men, standing in four ranks shoulder to shoulder, will form a line over a mile and a half long, and that’s close-packed heavy infantry such as Greek spearmen or Roman legionaries. If your troops are wild-eyed Celtic types who like a lot of space to swing their swords, it will be even longer.

Okay, that’s a little daunting, but Kearney also offers things like a breakdown of pre-gunpowder tactics into a set of relationships that he likens, persuasively, to rock-paper-scissors. If you can remember how that kindergarten game works, you can avoid some of the biggest beginner blunders in the genre.

…

Read More Read More

Until the end of the summer, this will probably be my last post at Black Gate. I’m moving, and that’s a good thing. Strenuous but good. My teaching schedule is almost entirely emptied out now, and the loose ends my students and I are tying up are all about foundational stuff, grammar and vocabulary. Tomorrow the house I’ve lived in for thirteen years starts emptying out, too.

Until the end of the summer, this will probably be my last post at Black Gate. I’m moving, and that’s a good thing. Strenuous but good. My teaching schedule is almost entirely emptied out now, and the loose ends my students and I are tying up are all about foundational stuff, grammar and vocabulary. Tomorrow the house I’ve lived in for thirteen years starts emptying out, too.

I got my first taste of Greek mythology from D’Aulaire’s Greek Myths. Later, when I was old enough for Bulfinch’s Mythology, I thought I had graduated to the real thing. Homer came to me by way of a dusty turn-of-the-century book with a title along the lines of The Boy’s Own Homer, with glorious color illustrations. D’Aulaire gave me the Norse myths, too, though I didn’t get The Ring of the Niebelungen until a friend gave me a mixtape that included

I got my first taste of Greek mythology from D’Aulaire’s Greek Myths. Later, when I was old enough for Bulfinch’s Mythology, I thought I had graduated to the real thing. Homer came to me by way of a dusty turn-of-the-century book with a title along the lines of The Boy’s Own Homer, with glorious color illustrations. D’Aulaire gave me the Norse myths, too, though I didn’t get The Ring of the Niebelungen until a friend gave me a mixtape that included  Paul Kearney’s piece on large-scale battle scenes is just what I hoped it would be. You know all the familiar gripes about fantasy warfare that fails the suspension-of-disbelief test: the army never seems to eat or excrete, never needs to get paid, charges its horses directly into walls of seasoned enemy pikemen, and so on. “So You Want to Fight a War” addresses all those mundane things an author must get right if the fantasy elements of her story are to feel real to the reader, and then Kearney pushes past the gripes into solutions that any conscientious author can learn to implement. It’s that last bit that I found truly refreshing — many discussions of military verisimilitude get bogged down in griping. Kearney assumes throughout that it’s possible for his reader to get this stuff right, with enough good models, research, and practice.

Paul Kearney’s piece on large-scale battle scenes is just what I hoped it would be. You know all the familiar gripes about fantasy warfare that fails the suspension-of-disbelief test: the army never seems to eat or excrete, never needs to get paid, charges its horses directly into walls of seasoned enemy pikemen, and so on. “So You Want to Fight a War” addresses all those mundane things an author must get right if the fantasy elements of her story are to feel real to the reader, and then Kearney pushes past the gripes into solutions that any conscientious author can learn to implement. It’s that last bit that I found truly refreshing — many discussions of military verisimilitude get bogged down in griping. Kearney assumes throughout that it’s possible for his reader to get this stuff right, with enough good models, research, and practice. Howard Andrew Jones’s “Two Sought Adventure” details the problems and potentials in stories that have more than one hero. A story with multiple heroes is very different from a one-hero story with a sidekick, love interest, foil, nemesis, or whatever. There are plenty of straightforward techniques for using secondary characters to reveal a single protagonist’s character. Using two (or more) heroes to do this for one another in a way that feels balanced and gratifying for the reader is a tougher trick. Dialogue is crucial, and Jones offers close readings of dialogue from his own work and others’ that illustrate ways to welcome the reader into the shorthand, in-jokes, and shifting tones in conversations between longtime friends. He also addresses a problem I’ve seen in too much professionally published fiction: the duo that bickers like an old married couple, to the point where you wish they would split up, go away, or get eaten by the monster already. Friends have conflict, and friends engaged in epic heroics may have epic conflicts, but bickering is only entertaining in small doses, and it’s rarely illuminating. Jones offers a variety of specific alternative ways to handle conflict between heroes, and to interweave it with a story’s other conflicts.

Howard Andrew Jones’s “Two Sought Adventure” details the problems and potentials in stories that have more than one hero. A story with multiple heroes is very different from a one-hero story with a sidekick, love interest, foil, nemesis, or whatever. There are plenty of straightforward techniques for using secondary characters to reveal a single protagonist’s character. Using two (or more) heroes to do this for one another in a way that feels balanced and gratifying for the reader is a tougher trick. Dialogue is crucial, and Jones offers close readings of dialogue from his own work and others’ that illustrate ways to welcome the reader into the shorthand, in-jokes, and shifting tones in conversations between longtime friends. He also addresses a problem I’ve seen in too much professionally published fiction: the duo that bickers like an old married couple, to the point where you wish they would split up, go away, or get eaten by the monster already. Friends have conflict, and friends engaged in epic heroics may have epic conflicts, but bickering is only entertaining in small doses, and it’s rarely illuminating. Jones offers a variety of specific alternative ways to handle conflict between heroes, and to interweave it with a story’s other conflicts.

It’s tempting to come up with some cheap shot punchline about how tax returns are a subgenre of fantasy literature. I’d poke at the puzzle longer, but I believe in the rule of law, so my tax returns are a good-faith attempt at nonfiction. There are times when I wish I hadn’t been drawn up as a Lawful Good character — goodness knows I tried at least to be Chaotic, but I could never keep it up for long.

It’s tempting to come up with some cheap shot punchline about how tax returns are a subgenre of fantasy literature. I’d poke at the puzzle longer, but I believe in the rule of law, so my tax returns are a good-faith attempt at nonfiction. There are times when I wish I hadn’t been drawn up as a Lawful Good character — goodness knows I tried at least to be Chaotic, but I could never keep it up for long. It’s good to be back at my Wednesday spot here at Black Gate. Two weeks ago, I got home from my favorite annual convention,

It’s good to be back at my Wednesday spot here at Black Gate. Two weeks ago, I got home from my favorite annual convention,