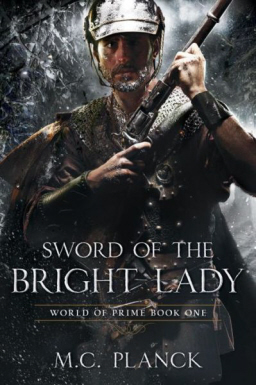

The Series Series: Sword of the Bright Lady by M.C. Planck

If you liked Eric Flint’s 1634 books, if you liked The Chronicles of Narnia, if you liked… Well let’s just start with those two, because Sword of the Bright Lady deals in surprising juxtapositions of familiar tropes.

If you liked Eric Flint’s 1634 books, if you liked The Chronicles of Narnia, if you liked… Well let’s just start with those two, because Sword of the Bright Lady deals in surprising juxtapositions of familiar tropes.

At times I wondered whether it dealt in anything deeper. I’ve concluded that it does. This is a fun book and it feels like it was fun to write. The author’s acknowledgments note that it took three months to write and ten years to revise. Am I churlish to wish the revision had gone one step further?

What works here works beautifully. Less than a day after I finished reading, I had to go back and prove to myself that the narration was in the third person, because I remembered Christopher’s adventures with first-person clarity, as if they had happened to me.

Christopher went out to walk his dogs one Arizona night and woke up in the snowy hinterlands of another world. His rescuers, an earthy old churchman and his orphaned servant girl, nurse him back to health, though they have no common language with him. When he’s well enough to pick up some of the household work, he tries practicing kata from his martial arts practice back home. Before he knows it, he’s challenged to a duel by a local nobleman, blessed by a language spell that allows him to understand exactly how much danger he’s in, and claimed by the local war god.

At first, Christopher insists that he’s an everyman, not famous back home nor expected to be famous by anyone who knew him there. But as he begins to see how he can help the people who have saved him, he accepts the identity the villagers thrust on him: “Crazy Pater Christopher, who never means what everyone else means.” He sets about industrializing his feudal neighbors — who all have lively personalities and complex lives — preparing them for the spring’s military campaign, because the war god Marcius has promised to return Christopher home to his beloved wife… um… what was her name again?

And that brings us to a sticking point I have to talk about. It’s not that M.C. Planck has done anything uncommonly wrong here, but rather that he’s fallen into a classic blunder that I see committed all over the place, but that nobody seems to talk about.

Let’s call it the Precious Ming Vase Problem.