Needling at Society’s Wounds: Horror in Pop Culture, From the 1950s to True Detective

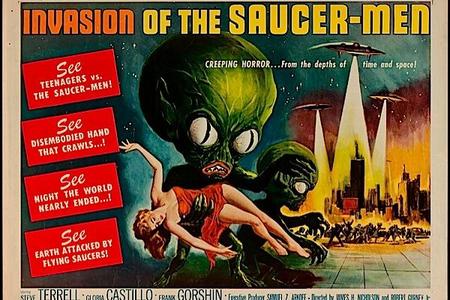

It appears near impossible to pinpoint what drives popular culture as it develops. If you look back through science fiction and horror of the nineteen fifties, you can hone in on Cold War undertones in retrospect, on the painful obviousness of America’s paranoia during its long conflict with the USSR. Fiction, and especially genre fiction, is a sponge for social anxieties. Horror in particular, since it thrives on fear, excels at needling at society’s wounds.

It appears near impossible to pinpoint what drives popular culture as it develops. If you look back through science fiction and horror of the nineteen fifties, you can hone in on Cold War undertones in retrospect, on the painful obviousness of America’s paranoia during its long conflict with the USSR. Fiction, and especially genre fiction, is a sponge for social anxieties. Horror in particular, since it thrives on fear, excels at needling at society’s wounds.

One need only turn to the seventies, as America moved beyond the optimism of the previous decade into a chilly, post-Summer of Love winter, to see the dynamic at play. The horror fiction during that time is so spectacular precisely because of how it responded to the decaying optimism of the previous generation. With the dream of Civil Rights leading to widespread racial inequality, with the closure of Vietnam, the introduction of long feather haircuts, the dissolution of the Beatles, and the rise of disco, society was wide open for big budget, socially scathing works of terror.

The eighties turned towards renewal and perceived stability, creating prolonged franchises and creature features that intermixed humor and gore with boatloads of camp. The nineties brought forth a self-referential realism that, in this author’s opinion, accompanied the economic boom of the Clinton years, where pre-9-11 excess bubbled in size and gave way to less politically indulgent modes of entertainment. In the current moment, however, in the wake of terrorism, global economic crisis, and two wars, one thing seems abundantly clear: we’ve returned to championing bleakness in pop culture that feels in many ways similar to what was seen in the seventies. But bleakness weaned on a new generation of plenty that can make the convention feel plastic, and even hypocritical, in nature.