The Last Dragon (1985): My Big Trouble in Little China or Black Panther Double Feature Pick

This week I have two reasons to write about The Last Dragon, aka Berry Gordy’s The Last Dragon. First, the biggest black superhero movie ever produced arrives in theaters this weekend, Black Panther. If projections are accurate, it will steamroller all February opening records with a domestic box-office take of $200 million and become a cultural touchstone for 2018. It’s the right time to celebrate with one of Black Panther’s earlier progenitors in black superhero movies that isn’t Blade. (Nothing against Blade, but it’s the example the other magazines will cover.)

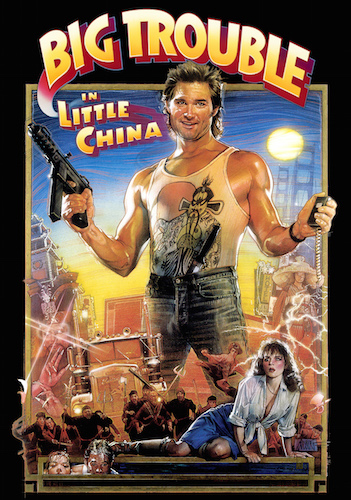

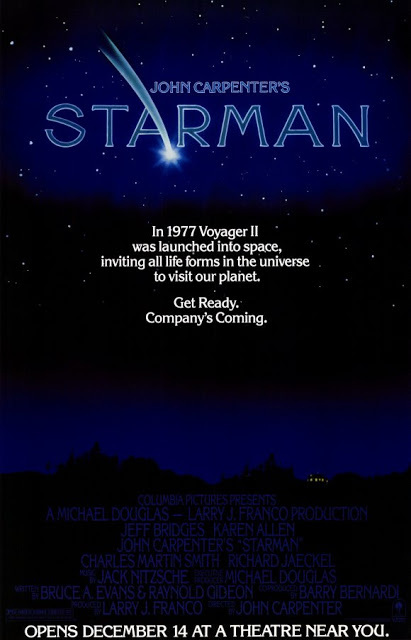

Second, I looked at Big Trouble in Little China last week for my John Carpenter series. Few films are a better fit for a double feature with Big Trouble in Little China than The Last Dragon, a martial arts comedy fantasy that came out the year before Carpenter’s take on a genre still unfamiliar to US audiences.

On a double bill with Big Trouble in Little China, I’d show The Last Dragon first. This is based on my guidelines for crafting double features — a subject I’ve given far too much thought — that either 1) the lesser quality film goes first, or 2) the lighter/less grim film goes second, whichever factor feels dominant. Since both movies are on the same level of buoyancy and feel-good fun, The Last Dragon opens for Big Trouble in Little China.