Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Mars, Part 6: The Master Mind of Mars

I maxed out on Barsoom back in March. After reviewing the first five Martian novels over a span of two and a half months, I switched over to writing about the movie John Carter of Mars. (That is what I’m calling it, dammit, because that’s what the end title card says.) I love the movie, but the box-office and the box-office pundits did not, and although I struggled to keep a positive view, I realized after all of this that I needed a break from Edgar Rice Burroughs’s red planet.

I maxed out on Barsoom back in March. After reviewing the first five Martian novels over a span of two and a half months, I switched over to writing about the movie John Carter of Mars. (That is what I’m calling it, dammit, because that’s what the end title card says.) I love the movie, but the box-office and the box-office pundits did not, and although I struggled to keep a positive view, I realized after all of this that I needed a break from Edgar Rice Burroughs’s red planet.

But during a brief pause between my summer movie reviews, the opportunity to zap my Earthly body back to Mars offered itself. So my overview of ERB’s Martian epic resumes at Book #6, with a new Earthman hero, a return to first-person, and the Barsoomian equivalent of The Island of Dr. Moreau.

Our Saga: The adventures of Earthman John Carter, his progeny, and sundry other natives and visitors, on the planet Mars, known to its inhabitants as Barsoom. A dry and slowly dying world, Barsoom contains four different human civilizations, one non-human one, a scattering of science among swashbuckling, and a plethora of religions, mystery cities, and strange beasts. The series spans 1912 to 1964 with nine novels, one volume of linked novellas, and two unrelated novellas.

Today’s Installment: The Master Mind of Mars (1927)

Previous Installments: A Princess of Mars (1912), The Gods of Mars (1913), The Warlord of Mars (1913-14), Thuvia, Maid of Mars (1916), The Chessmen of Mars (1922)

The Backstory

Burroughs wrote The Master Mind of Mars (originally under the less thrilling titles “A Weird Adventure on Mars” and “Vad Varo of Barsoom”) in mid-1925, but his usual markets didn’t pick it up. (Wikipedia, in a [citation needed] moment, speculates this may have something to do with “its satirical treatment of religious fundamentalists.” That seems unlikely, as the book is light on the religious criticism compared to the instant-selling The Gods of Mars, where searing attacks on religion are the center of the plot.) ERB finally sold the book to Hugo Gernsback, inventor of the term “science fiction,” pioneer of magazine SF, and notorious cheapskate, who paid $1,250 for the novel — much less than what the author got from his usual markets. Gernsback made Burroughs’s newest Martian adventure the lead story for his Amazing Stories Annual, an extension of what was at the time the only science-fiction pulp. Burroughs made sense as a circulation-booster, since he helped create magazine SF fourteen years before the first pulp dedicated to it appeared on the stands. …

Who would think at the start of the summer that Brave was concealing more of its plot and themes than

Who would think at the start of the summer that Brave was concealing more of its plot and themes than  I have a week-long break between summer movie reviews, the gap between

I have a week-long break between summer movie reviews, the gap between  If you plan to see Prometheus this weekend, know that you are in for an endless buffet of visual astonishment, especially if you spring to see it in IMAX 3D. Ridley Scott belongs to the breed of filmmaker who can justify the use of the 3D gimmick. He poured everything at his disposal to make his new science-fiction film worth the extra dollars, euros, pound notes needed to watch it in an immersive environment. Prometheus is visual and aural splendor for the cinema.

If you plan to see Prometheus this weekend, know that you are in for an endless buffet of visual astonishment, especially if you spring to see it in IMAX 3D. Ridley Scott belongs to the breed of filmmaker who can justify the use of the 3D gimmick. He poured everything at his disposal to make his new science-fiction film worth the extra dollars, euros, pound notes needed to watch it in an immersive environment. Prometheus is visual and aural splendor for the cinema. Summer movies, like boxes of Crackerjacks (does anyone still eat those? I never see them for sale any more), come packed with surprises. And, like Crackerjacks toys, often they are lame surprises. Let-downs. Occasionally — and it usually happens only once per summer — the toy you dig out of the same-old same-old caramel and peanut glop is a Hot Wheels car with flame details and killer sci-fi spoilers that somebody in the Crackerjack plant accidentally dropped into the box while leaving hastily for a smoke break.

Summer movies, like boxes of Crackerjacks (does anyone still eat those? I never see them for sale any more), come packed with surprises. And, like Crackerjacks toys, often they are lame surprises. Let-downs. Occasionally — and it usually happens only once per summer — the toy you dig out of the same-old same-old caramel and peanut glop is a Hot Wheels car with flame details and killer sci-fi spoilers that somebody in the Crackerjack plant accidentally dropped into the box while leaving hastily for a smoke break. Before getting into Men in Black Part the Third, I must retract a promise made in an earlier post, where I

Before getting into Men in Black Part the Third, I must retract a promise made in an earlier post, where I  You sunk my interest.

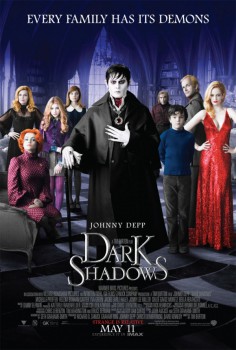

You sunk my interest. Dark Shadows is the first victim of

Dark Shadows is the first victim of

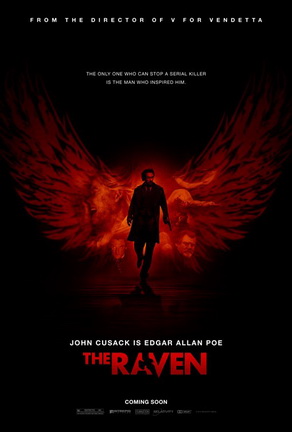

The Raven (2012)

The Raven (2012)