The Steel Seraglio: a Review

The Steel Seraglio

The Steel Seraglio

Mike, Linda, and Louise Carey

ChiZine Publications (424 pp, $15.95 US/$17.95 CAD, trade paperback)

Reviewed by Matthew Surridge

The Steel Seraglio is a fantasy novel by husband/wife/daughter trio Mike, Linda, and Louise Carey, put out by ChiZine Publications. There’s also a chapbook set in the same world (which you might be able to get if you order the book directly from ChiZine). It’s a story set in a pseudo-historical Arabia, in a desert of city-states ruled by sultans. When religious zealots stage a revolution in the city of Bessa, a chain of events is set in motion that results in the former Sultan’s former harem of 365 women banding together to take the city back, and installing their own enlightened rule. The book tells the story of the women, and the rise and fall of the city they make.

I thought it was a decent adventure novel with some nice touches; good enough, and the touches nice enough, that I wished it had been better — either a better adventure, or a better novel. I think the book narrowly fails to achieve all the grand effects that it aims for, mostly due to staging and logic that don’t feel entirely thought-through. And I think that what is most interesting about the book, specifically its narrative structure and use of narrative to establish character, is not particularly well-served by the epic adventure format. I also found I had some qualms about the setting, or at least how the setting was developed in the course of the story.

Today, July 1, is the one-hundred-and-forty-fifth anniversary of the date the

Today, July 1, is the one-hundred-and-forty-fifth anniversary of the date the  This is the second part of a look at Rush, whose new steampunk epic Clockwork Angels came out earlier this month. I think it’s a wonderful album, but to explain why it seemed to me worth looking at their earlier work — I looked at what they’ve accomplished as a band, and what drummer and lyricist Neil Peart has become as a writer. Last time, I looked at their records up through 1978’s Hemispheres; I therefore begin here in 1980, with the next album, Permanent Waves. (You can find that first post

This is the second part of a look at Rush, whose new steampunk epic Clockwork Angels came out earlier this month. I think it’s a wonderful album, but to explain why it seemed to me worth looking at their earlier work — I looked at what they’ve accomplished as a band, and what drummer and lyricist Neil Peart has become as a writer. Last time, I looked at their records up through 1978’s Hemispheres; I therefore begin here in 1980, with the next album, Permanent Waves. (You can find that first post  I’ve been writing a fair bit lately about Canadian fantastika, and I’ll be doing so again next week, looking at a trio of grand masters who’ve just released what may be one of the most accomplished works of their career. But there’s been a bit of news lately about another notorious Canadian fantasy epic, so I want to talk about that first.

I’ve been writing a fair bit lately about Canadian fantastika, and I’ll be doing so again next week, looking at a trio of grand masters who’ve just released what may be one of the most accomplished works of their career. But there’s been a bit of news lately about another notorious Canadian fantasy epic, so I want to talk about that first. Fall From Earth

Fall From Earth Triptych

Triptych Westlake Soul is twenty-three, a good-natured surfing champion with a loving family, loving girlfriend, and loving dog. Then a terrible fall leaves him in a vegetative state, unresponsive to the outside world — but, locked in his own mind, he’s a superintelligent superhero, astrally projecting to the moon and battling the mysterious villain named Doctor Quietus. Westlake can’t affect the outside world; can’t even twitch a finger, can only sit and be cared for by his mother and father and little sister, and the nurses they hire. But he can see what goes on around him, and react, if only internally.

Westlake Soul is twenty-three, a good-natured surfing champion with a loving family, loving girlfriend, and loving dog. Then a terrible fall leaves him in a vegetative state, unresponsive to the outside world — but, locked in his own mind, he’s a superintelligent superhero, astrally projecting to the moon and battling the mysterious villain named Doctor Quietus. Westlake can’t affect the outside world; can’t even twitch a finger, can only sit and be cared for by his mother and father and little sister, and the nurses they hire. But he can see what goes on around him, and react, if only internally.

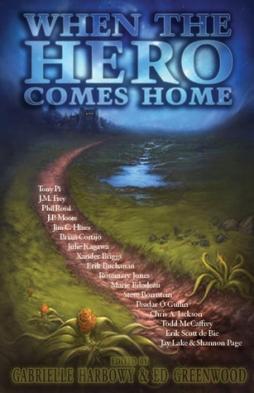

When the Hero Comes Home is an anthology from Dragon Moon Press co-edited by Garbielle Harbowy and Ed Greenwood. It’s a surprisingly thin book, given that it holds nineten stories by twenty writers (including two Black Gate contributors, Peadar Ó Guilín and Jay Lake, in collaboration with Shannon Page). Its theme is exactly what it says: the homecoming. The point where the story usually ends. I have some reservations about how the book turned out, but the idea’s intriguing: what do you find when you make it back to where you began? Has the place changed, or have you?

When the Hero Comes Home is an anthology from Dragon Moon Press co-edited by Garbielle Harbowy and Ed Greenwood. It’s a surprisingly thin book, given that it holds nineten stories by twenty writers (including two Black Gate contributors, Peadar Ó Guilín and Jay Lake, in collaboration with Shannon Page). Its theme is exactly what it says: the homecoming. The point where the story usually ends. I have some reservations about how the book turned out, but the idea’s intriguing: what do you find when you make it back to where you began? Has the place changed, or have you?