Ursula Vernon’s Digger

The Hugo Award for Best Graphic Story was first given out in 2009. The category was a nice idea, especially given the increased prominence of comics in the media landscape, but I have to admit that up to this year, I’ve been underwhelmed by the choice of winners. Or, more precisely, winner, singular: Phil and Kaja Foglio’s webcomic Girl Genius took the award three times straight. I don’t dislike the comic, but from what I’ve read, I’d be hard-pressed to identify anything in it that makes it worth a major award ahead of any number of series — Hellboy or Mouse Guard or Wednesday Comics or RASL or All-Star Superman or you name it. After their third win, though, the Foglios announced they would decline to accept a nomination for the next year, in the interest of helping to establish the validity of the award. So the 2012 Hugo went to another title: Digger, a webcomic by Ursula Vernon. I find it’s much more interesting.

The Hugo Award for Best Graphic Story was first given out in 2009. The category was a nice idea, especially given the increased prominence of comics in the media landscape, but I have to admit that up to this year, I’ve been underwhelmed by the choice of winners. Or, more precisely, winner, singular: Phil and Kaja Foglio’s webcomic Girl Genius took the award three times straight. I don’t dislike the comic, but from what I’ve read, I’d be hard-pressed to identify anything in it that makes it worth a major award ahead of any number of series — Hellboy or Mouse Guard or Wednesday Comics or RASL or All-Star Superman or you name it. After their third win, though, the Foglios announced they would decline to accept a nomination for the next year, in the interest of helping to establish the validity of the award. So the 2012 Hugo went to another title: Digger, a webcomic by Ursula Vernon. I find it’s much more interesting.

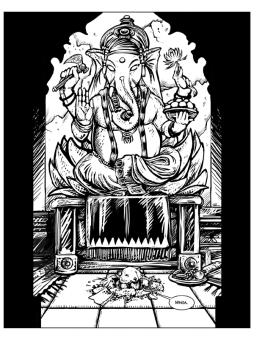

Digger is a 759-page fantasy story (free online, or available in six printed volumes) about a talking tough-as-nails wombat named Digger-of-Unnecessarily-Convoluted-Tunnels, who gets lost and finds herself in a strange land filled with gods, humanoid hyenas, magic, oracular snails, and mysteries. Digger wants to get home, but it looks like some unknown force has manipulated events to bring her to the temple of Ganesh where she surfaces. Who and why? That’s the central mystery that unfolds through the tale. Digger makes friends, makes enemies, and takes several harrowing journeys before all is settled.

It’s a comedy, and an effective one, but with a number of serious themes running through it. Vernon seems to have something to say, and the talent to say it well. Her storytelling’s strong, and she handles mythology deftly — both the mythology of various cultures of our world and the mythology of the story she’s creating.

I’ve been thinking a fair bit lately about how I read what I read, and how I enjoy it. Or, what’s in it that I enjoy. It seems to me that much of the pleasure in my reading comes about from bad habits. Which is to say, habits that I can’t help but think ought to be bad, but which nevertheless feel central to the act of reading. Maybe that feeling’s an illusion; maybe it’s the secret why bad habits become habits. At any rate, I thought I’d be self-indulgent this week and throw out what I’ve come up with, as I’d love to hear if any of it resonates with anyone else’s experience of reading.

I’ve been thinking a fair bit lately about how I read what I read, and how I enjoy it. Or, what’s in it that I enjoy. It seems to me that much of the pleasure in my reading comes about from bad habits. Which is to say, habits that I can’t help but think ought to be bad, but which nevertheless feel central to the act of reading. Maybe that feeling’s an illusion; maybe it’s the secret why bad habits become habits. At any rate, I thought I’d be self-indulgent this week and throw out what I’ve come up with, as I’d love to hear if any of it resonates with anyone else’s experience of reading. There was a time in the 1980s when it looked like Marvel and DC Comics might slowly evolve into something like mainstream book publishers: publishers who gave creators fair deals respecting copyright, and who lived off of the publication of new titles rather than the exploitation of intellectual property from decades previous. That hasn’t really happened, so far as I can see. Both companies dabbled in various kinds of creator ownership, but both appear mostly to have retreated to the relative safety of work-for-hire deals in recent years. Vertigo, a DC imprint featuring better deals for creators, seems to have become more strict in their contracts, and the

There was a time in the 1980s when it looked like Marvel and DC Comics might slowly evolve into something like mainstream book publishers: publishers who gave creators fair deals respecting copyright, and who lived off of the publication of new titles rather than the exploitation of intellectual property from decades previous. That hasn’t really happened, so far as I can see. Both companies dabbled in various kinds of creator ownership, but both appear mostly to have retreated to the relative safety of work-for-hire deals in recent years. Vertigo, a DC imprint featuring better deals for creators, seems to have become more strict in their contracts, and the  As so often happens, I was at a book fair the other week when, again as so often happens, I stumbled on a book by a writer I’d heard of at some point and about whose work I was vaguely curious. In this case, the writer was Zenna Henderson and the book was a collection of sf and fantasy short stories called The Anything Box. Which, upon reading, I found to be quite intriguing.

As so often happens, I was at a book fair the other week when, again as so often happens, I stumbled on a book by a writer I’d heard of at some point and about whose work I was vaguely curious. In this case, the writer was Zenna Henderson and the book was a collection of sf and fantasy short stories called The Anything Box. Which, upon reading, I found to be quite intriguing. Typically in these blog posts, I write about some work of fantasy, science fiction, or horror; of fantastika. I’m not sure whether the book I want to write about this time round can be described as any of those things. It’s not always, in fact, easy to distinguish what is fantastic and what is not. Does the distinction lie in what the writer has in mind, or in how the reader interprets the text? If a man who believes himself to be a magician writes about magic, is that fantasy or mimetic fiction? The author describes the world as the author understands it. The reader, reading, then sees the world as the author does: so writing is perhaps inherently magical, a possession. All words are magic words. All stories are true.

Typically in these blog posts, I write about some work of fantasy, science fiction, or horror; of fantastika. I’m not sure whether the book I want to write about this time round can be described as any of those things. It’s not always, in fact, easy to distinguish what is fantastic and what is not. Does the distinction lie in what the writer has in mind, or in how the reader interprets the text? If a man who believes himself to be a magician writes about magic, is that fantasy or mimetic fiction? The author describes the world as the author understands it. The reader, reading, then sees the world as the author does: so writing is perhaps inherently magical, a possession. All words are magic words. All stories are true. For some time I’ve had the idea that there are unknown treasures yet to be mined in the deep veins of 80s fantasy. That among all the many titles published in those years are overlooked tales that are worth digging up. I don’t necessarily mean neglected masterpieces, though that’s possible. I mean little gems: books offering unexpected or idiosyncratic takes on the genre. Books that to some extent operate by conventions of their own. Books that suggest slightly different ways to do things. I want to write here about an example of what I mean: Phyllis Ann Karr’s At Amberleaf Fair.

For some time I’ve had the idea that there are unknown treasures yet to be mined in the deep veins of 80s fantasy. That among all the many titles published in those years are overlooked tales that are worth digging up. I don’t necessarily mean neglected masterpieces, though that’s possible. I mean little gems: books offering unexpected or idiosyncratic takes on the genre. Books that to some extent operate by conventions of their own. Books that suggest slightly different ways to do things. I want to write here about an example of what I mean: Phyllis Ann Karr’s At Amberleaf Fair. A little while ago, Fearless Leader John O’Neill

A little while ago, Fearless Leader John O’Neill  I don’t remember where I first came across Ursula Pflug’s name. I know I’d seen it mentioned in several places before I stumbled across a collection of her short stories, After the Fires, at a recent book sale. From what I’d heard, she was a Canadian writer of literary fantasy, which was enough for me to take a chance on the book. On the whole, I think that was a good call.

I don’t remember where I first came across Ursula Pflug’s name. I know I’d seen it mentioned in several places before I stumbled across a collection of her short stories, After the Fires, at a recent book sale. From what I’d heard, she was a Canadian writer of literary fantasy, which was enough for me to take a chance on the book. On the whole, I think that was a good call. Arthur Machen first published a version of “The Great God Pan” in 1890, in a magazine called The Whirlwind; then revised and extended the tale for its republication as a book in 1894, when it was accompanied by a thematically-similar story called “The Inner Light.” It’s a fascinating work, creating a horrific mood mostly through suggestion and indirection. Nowadays, one looks at it and notes very Victorian attitudes toward women. At the time of its original publication, the story’s implied sexuality caused real scandal.

Arthur Machen first published a version of “The Great God Pan” in 1890, in a magazine called The Whirlwind; then revised and extended the tale for its republication as a book in 1894, when it was accompanied by a thematically-similar story called “The Inner Light.” It’s a fascinating work, creating a horrific mood mostly through suggestion and indirection. Nowadays, one looks at it and notes very Victorian attitudes toward women. At the time of its original publication, the story’s implied sexuality caused real scandal. For the past three weeks, I’ve been looking at Joyce Carol Oates’s Gothic Quintet, in preparation for the publication of the fifth book in the sequence, The Accursed, set for next March. I started off with 1980’s

For the past three weeks, I’ve been looking at Joyce Carol Oates’s Gothic Quintet, in preparation for the publication of the fifth book in the sequence, The Accursed, set for next March. I started off with 1980’s