“What If Luck Wasn’t a Matter of Chance?”: OXV: The Manual

The 2013 edition of Montreal’s Fantasia film festival is well underway and I’ve been able to see three films so far, with more planned. A few days ago, I watched The Garden of Words, a visually spectacular 45-minute slice-of-life anime, and at noon yesterday took in After School Midnighters, a kid-oriented 3D animated movie that nicely balances plot and wackiness. Then, later that afternoon, I attended a showing of OXV: The Manual, a science-fiction film premiering at the festival. I was impressed enough to want to write about it here.

The 2013 edition of Montreal’s Fantasia film festival is well underway and I’ve been able to see three films so far, with more planned. A few days ago, I watched The Garden of Words, a visually spectacular 45-minute slice-of-life anime, and at noon yesterday took in After School Midnighters, a kid-oriented 3D animated movie that nicely balances plot and wackiness. Then, later that afternoon, I attended a showing of OXV: The Manual, a science-fiction film premiering at the festival. I was impressed enough to want to write about it here.

OXV is an exceptionally strong film, not flawless, but dedicated to its ideas and the science-fictional notions driving its plot. At its core are questions of determinism and free will, questions the movie builds to and explores rigorously. Around these themes it subtly but surely builds a kind of alternate reality, then over the course of its story develops that reality in ways that we don’t expect. The structure of the film is complex without being hard to follow, and opens up into a larger tale than we might at first suspect. Overall, it’s hard not to think of Primer while watching it; it’s not that the two films are similar, but they’re both good films that tell truly science-fictional stories on relatively limited budgets.

In a world, and specifically an England, where people’s relative levels of luck have been measured scientifically, an absurdly unlucky boy falls in love with the luckiest girl in the world. The boy has a low ‘frequency,’ the girl a high one; they cancel each other out and create wildly improbable events if they spend more than a minute together. Young Isaac Newton — in this world, people are named for great scientists and thinkers; Isaac’s known as Zak — persists in loving Marie anyway, despite the fact that a side-effect of her high frequency is a lack of emotion. With his friend, Theodore Adorno Strauss, he struggles to come up with a way to change his frequency. They succeed, developing a ‘manual’ that suggests words that alter the speaker’s luck. The movie develops from there, exploring ramifications and unintended consequences of their discovery.

Normally, I write here about fantasy (which to me includes science fiction and horror). But some mimetic novels have a lot to say about the fantastic. Or a lot to say about related themes; wonder, for example, or the numinous. Those books are sometimes worth discussing at Black Gate, I think. Which is why I want to write now about Robertson Davies’s Deptford Trilogy — classics of Canadian literature, novels deeply concerned with wonder — and consider whether they should have been even more open to the fantastic than they in fact are.

Normally, I write here about fantasy (which to me includes science fiction and horror). But some mimetic novels have a lot to say about the fantastic. Or a lot to say about related themes; wonder, for example, or the numinous. Those books are sometimes worth discussing at Black Gate, I think. Which is why I want to write now about Robertson Davies’s Deptford Trilogy — classics of Canadian literature, novels deeply concerned with wonder — and consider whether they should have been even more open to the fantastic than they in fact are. One of the distinct pleasures of book fairs and used book sales is finding an intriguing book you’ve never heard of. A greater and related pleasure comes when that book turns out to be quite good. Then, in reaction to that, there’s a melancholy that sets in from the fact that a worthwhile book is largely unknown. I’d like to think I can take the edge off that last sense by writing about some of these books here. So, given all that, a few words about Virgil Burnett’s Towers at the Edge of a World:

One of the distinct pleasures of book fairs and used book sales is finding an intriguing book you’ve never heard of. A greater and related pleasure comes when that book turns out to be quite good. Then, in reaction to that, there’s a melancholy that sets in from the fact that a worthwhile book is largely unknown. I’d like to think I can take the edge off that last sense by writing about some of these books here. So, given all that, a few words about Virgil Burnett’s Towers at the Edge of a World: A couple Wednesdays ago, I did something I haven’t done in ages. I went down to my local comic store on new-comic day (which is Wednesdays) and bought a new super-hero comic off the rack. Not a Marvel or DC book, though — not really, though it was published by DC’s Vertigo imprint. This was the return of a series first published in 1995, under the Image Comics banner. The title’s moved around a fair bit since, and frequently been on hiatus from regular publication. But it’s back now, and hopefully for a long time to come. It’s Kurt Busiek’s Astro City, and I want to talk about what it is and why I’m going to be buying it going forward.

A couple Wednesdays ago, I did something I haven’t done in ages. I went down to my local comic store on new-comic day (which is Wednesdays) and bought a new super-hero comic off the rack. Not a Marvel or DC book, though — not really, though it was published by DC’s Vertigo imprint. This was the return of a series first published in 1995, under the Image Comics banner. The title’s moved around a fair bit since, and frequently been on hiatus from regular publication. But it’s back now, and hopefully for a long time to come. It’s Kurt Busiek’s Astro City, and I want to talk about what it is and why I’m going to be buying it going forward. ‘Magic’ is an elastic metaphor. Among its many possible uses is that of a descriptor for something that happens in performance, especially live performance: the magic of an actor possessed by a character, the magic of a given moment invested with wonder and remaining in the memory, though inevitably passing away. The magic of stage magicians isn’t in the sleight-of-hand; it’s in the effect on the audience. The related magic of the carnival — the amusement park, the theme park — is a kind of second-person secondary-world magic. You are there. You are in a conjured fantasyland. A circus, in this reading, isn’t about the stink of animals or the scutwork of putting up tents and preparing performance spaces; it’s about the feeling the show tries to inspire. It is, potentially, for some, a venue for magic — transient, susceptible to thinning, but capable of generating wonder.

‘Magic’ is an elastic metaphor. Among its many possible uses is that of a descriptor for something that happens in performance, especially live performance: the magic of an actor possessed by a character, the magic of a given moment invested with wonder and remaining in the memory, though inevitably passing away. The magic of stage magicians isn’t in the sleight-of-hand; it’s in the effect on the audience. The related magic of the carnival — the amusement park, the theme park — is a kind of second-person secondary-world magic. You are there. You are in a conjured fantasyland. A circus, in this reading, isn’t about the stink of animals or the scutwork of putting up tents and preparing performance spaces; it’s about the feeling the show tries to inspire. It is, potentially, for some, a venue for magic — transient, susceptible to thinning, but capable of generating wonder. I picked up Helen Oyeyemi’s third novel, 2009’s White is for Witching, knowing very little about it. I’d read that Oyeyemi was a highly-regarded young writer in ‘mainstream’ literary circles, whose work contained some speculative elements (born in 1984, her first book had been 2005’s The Icarus Girl, followed by The Opposite House in 2007; a fourth book, Mr Fox, came out in 2011). What I found in White is for Witching was an excellent horror story whose intricacy demanded careful attention. It’s sharply-written and tightly-constructed, and if its plot is not immediately clear, the book’s strong enough to encourage careful attention.

I picked up Helen Oyeyemi’s third novel, 2009’s White is for Witching, knowing very little about it. I’d read that Oyeyemi was a highly-regarded young writer in ‘mainstream’ literary circles, whose work contained some speculative elements (born in 1984, her first book had been 2005’s The Icarus Girl, followed by The Opposite House in 2007; a fourth book, Mr Fox, came out in 2011). What I found in White is for Witching was an excellent horror story whose intricacy demanded careful attention. It’s sharply-written and tightly-constructed, and if its plot is not immediately clear, the book’s strong enough to encourage careful attention. There’s a distinctive kind of surprise some science fiction books can generate: surprise that a book which seems to be speaking to the beliefs, fears, or world-view of a given time was in fact written well beforehand. I remember being taken aback, for example, that A Clockwork Orange was first published in 1962, before hippies and punks and the coining of ‘generation gap’ (first recorded 1967). And it’s interesting to me that Maureen F. McHugh’s China Mountain Zhang, published in 1992, calmly and thoroughly imagines a future dominated by China — something much discussed today, but a less common idea before the turn of the millennium. McHugh’s book is a twentieth century novel, lacking a world wide web or smartphones, that speaks to the twenty-first.

There’s a distinctive kind of surprise some science fiction books can generate: surprise that a book which seems to be speaking to the beliefs, fears, or world-view of a given time was in fact written well beforehand. I remember being taken aback, for example, that A Clockwork Orange was first published in 1962, before hippies and punks and the coining of ‘generation gap’ (first recorded 1967). And it’s interesting to me that Maureen F. McHugh’s China Mountain Zhang, published in 1992, calmly and thoroughly imagines a future dominated by China — something much discussed today, but a less common idea before the turn of the millennium. McHugh’s book is a twentieth century novel, lacking a world wide web or smartphones, that speaks to the twenty-first. Growing up reading superhero comic books, it was almost inevitable that I’d hear about Philip Wylie’s 1930 novel Gladiator. It was said to be the inspiration behind Superman, the original story about an ultra-powerful strong man who set about trying to right wrongs. Growing older, I heard more: that Jerry Siegel, Superman’s co-creator, had reviewed the book for a fanzine; that he’d swiped dialogue from the book for use in his comics; that Wylie had threatened to sue.

Growing up reading superhero comic books, it was almost inevitable that I’d hear about Philip Wylie’s 1930 novel Gladiator. It was said to be the inspiration behind Superman, the original story about an ultra-powerful strong man who set about trying to right wrongs. Growing older, I heard more: that Jerry Siegel, Superman’s co-creator, had reviewed the book for a fanzine; that he’d swiped dialogue from the book for use in his comics; that Wylie had threatened to sue.  Last October, I looked at the four books of Joyce Carol Oates’ Gothic Quintet that had been published up to that point. I wrote about them in publication order, starting with

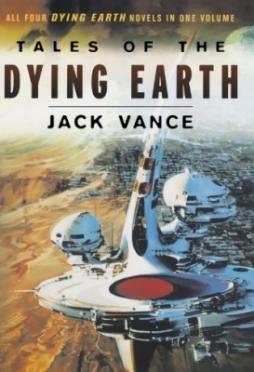

Last October, I looked at the four books of Joyce Carol Oates’ Gothic Quintet that had been published up to that point. I wrote about them in publication order, starting with  Last Sunday, May 26, veteran genre writer Jack Vance died at the age of 96. John O’Neill posted

Last Sunday, May 26, veteran genre writer Jack Vance died at the age of 96. John O’Neill posted