The Clothes Make the Mage: Alan Moore’s Fashion Beast

It seems like one of those creative pairings that could only happen in comics. Odd, then, that it was originally planned to be a film.

It seems like one of those creative pairings that could only happen in comics. Odd, then, that it was originally planned to be a film.

In the mid-1980s, fashion and music impresario Malcolm McLaren called acclaimed comics writer Alan Moore. It seemed McLaren had some ideas for a film he wanted to make. The two men met and Moore was fascinated by one of McLaren’s notions: a movie that would be a modern retelling of the fairy-tale of “Beauty and the Beast,” to be set in the fashion industry — or a strange fantastical version thereof. You can see the connection: a fable about the conflict between exterior appearances and internal natures, set in a milieu that was all about appearances. Moore wrote a script titled Fashion Beast, apparently as heavily detailed as any of his comics work; in an interview with The Comics Journal a few years later, he mentioned that McLaren had observed that he’d left very little for a director to do with the film. In any event, the production never happened and the project was abandoned.

Until 2012, when Avatar press resurrected the script. With Moore’s blessing, Antony Johnston signed on to adapt the film script to comics. With art by Facundo Percio (and colours by Hernan Cabrera and lettering by Jaymes Reed), the movie script became a ten-issue limited series, now collected in a trade paperback. It’s an odd project, but the final result’s quite strong. It may not be of the same calibre as Watchmen, but it’s a very good story that seems to me to compare well with much of Moore’s other work of the period — in the range of his Swamp Thing run, say, perhaps even of V For Vendetta.

February is

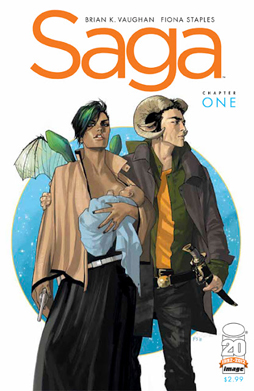

February is  A few months ago, the 2013 Hugo Award for Best Graphic Story was given to Saga, Volume 1, the first trade paperback collection of the ongoing Saga comic book. Written by Brian K. Vaughan, with art by Fiona Staples (and lettering and design by the Fonografiks studio), the book deserved the win. It’s the first chapter in a promising story and manages to establish a simple and powerful basic situation for the main characters, while also creating a complex world, backstory, and array of subplots. If it sometimes seems overbroad, too accessible and glib, it also has a deep and original sense of history to its setting, and a design sense that makes that setting live.

A few months ago, the 2013 Hugo Award for Best Graphic Story was given to Saga, Volume 1, the first trade paperback collection of the ongoing Saga comic book. Written by Brian K. Vaughan, with art by Fiona Staples (and lettering and design by the Fonografiks studio), the book deserved the win. It’s the first chapter in a promising story and manages to establish a simple and powerful basic situation for the main characters, while also creating a complex world, backstory, and array of subplots. If it sometimes seems overbroad, too accessible and glib, it also has a deep and original sense of history to its setting, and a design sense that makes that setting live. A little while ago, I followed a retweeted link to

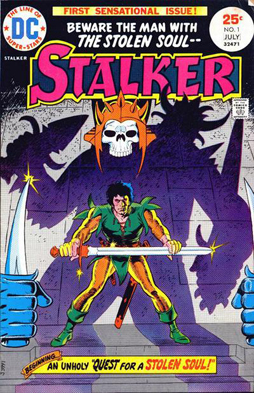

A little while ago, I followed a retweeted link to  The first stop I made on my shopping expedition last Boxing Day was at my local neighbourhood comics store, which happens to be conveniently located two and a half blocks from my house. There, I found a deal in the back-issue bins: issues 1 to 4 of Stalker, a DC fantasy comic from the 70s. I’d vaguely heard of the title, but knew nothing about it. I thought I remembered hearing that it had good art, which I imagined perhaps meant work by somebody like Nestor Redondo or Ernie Chan. I was way off. In fact, the art was by the remarkable team of Steve Ditko and Wally Wood. As a result, it’s wonderful. And more than that: it’s truly weird fantasy art in every sense.

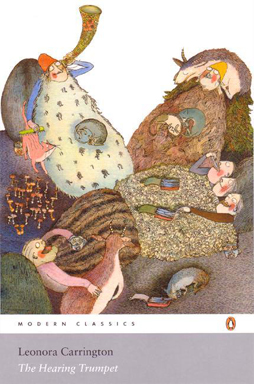

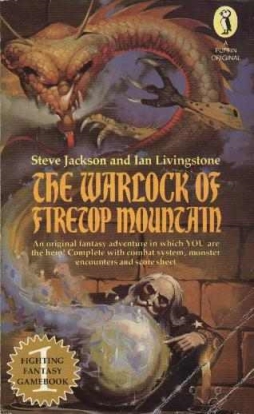

The first stop I made on my shopping expedition last Boxing Day was at my local neighbourhood comics store, which happens to be conveniently located two and a half blocks from my house. There, I found a deal in the back-issue bins: issues 1 to 4 of Stalker, a DC fantasy comic from the 70s. I’d vaguely heard of the title, but knew nothing about it. I thought I remembered hearing that it had good art, which I imagined perhaps meant work by somebody like Nestor Redondo or Ernie Chan. I was way off. In fact, the art was by the remarkable team of Steve Ditko and Wally Wood. As a result, it’s wonderful. And more than that: it’s truly weird fantasy art in every sense. It’s a time for looking back, as the old year ends. Now so it happens that on a Boxing Day sale I picked up a book I loved as a child; and therefore it seems fitting to write a little about it, now, glancing back down the vanished days of this and other years, and to try to again see the pleasure I once had. Will it come again, as I work through the text? If I work on the text, then no. Because this text, more than most, is not made for working. It is a thing to be played.

It’s a time for looking back, as the old year ends. Now so it happens that on a Boxing Day sale I picked up a book I loved as a child; and therefore it seems fitting to write a little about it, now, glancing back down the vanished days of this and other years, and to try to again see the pleasure I once had. Will it come again, as I work through the text? If I work on the text, then no. Because this text, more than most, is not made for working. It is a thing to be played. For some years now I’ve been wanting to reread Virginia Woolf’s Orlando. I first read the book about twenty years ago, and though I enjoyed it I came away confused. I felt as though on some level I really hadn’t understood the book. As though I hadn’t grasped how to read it. So, time having passed and me having (maybe) come to understand a bit more about books and reading, I sat down with Orlando again. And, as I’d hoped, I enjoyed it more thoroughly this time around, and felt as though I’d understood it a little better than I had. What surprised me was the reason for that understanding. I felt as though I’d worked out how to approach the book not because of any greater knowledge of modernism, or even because I’d read other books by Woolf, but because I now had a greater experience of early fantasy. More than I’d remembered or understood when I first read the book, Orlando is of a piece with the fantastic fiction of its time.

For some years now I’ve been wanting to reread Virginia Woolf’s Orlando. I first read the book about twenty years ago, and though I enjoyed it I came away confused. I felt as though on some level I really hadn’t understood the book. As though I hadn’t grasped how to read it. So, time having passed and me having (maybe) come to understand a bit more about books and reading, I sat down with Orlando again. And, as I’d hoped, I enjoyed it more thoroughly this time around, and felt as though I’d understood it a little better than I had. What surprised me was the reason for that understanding. I felt as though I’d worked out how to approach the book not because of any greater knowledge of modernism, or even because I’d read other books by Woolf, but because I now had a greater experience of early fantasy. More than I’d remembered or understood when I first read the book, Orlando is of a piece with the fantastic fiction of its time. It’s one of the most famous stories in the English-speaking world, and it is a fantasy. A Gothic fantasy of Christmas, and the meaning thereof: the story of the miser and the three spirits. It’s been retold any number of times, parodied, set in America, updated to the modern day, acted out with mice and ducks, with frogs and pigs. It’s easy to overlook how powerful the original work really is.

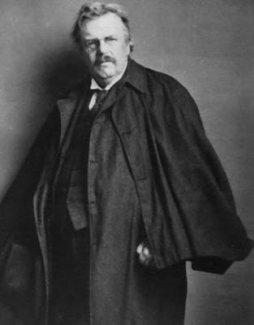

It’s one of the most famous stories in the English-speaking world, and it is a fantasy. A Gothic fantasy of Christmas, and the meaning thereof: the story of the miser and the three spirits. It’s been retold any number of times, parodied, set in America, updated to the modern day, acted out with mice and ducks, with frogs and pigs. It’s easy to overlook how powerful the original work really is. Last week, in a post about Neil Gaiman’s Sandman, I said that certain habits of Gaiman’s plotting reminded me of G.K. Chesterton. It seemed to me that I’d referred to Chesterton fairly often in my posts here, so I did a search of the Black Gate archive. I found that I had in fact mentioned Chesterton a number of times, but that neither I nor anyone else had yet written a post for Black Gate specifically about him or any of his works. I’ve therefore put together this piece to give an overview of the man and his writing. It’s insufficient; Chesterton’s difficult to describe, more so than most writers. But one has to begin somewhere. He’s an important early fantasist, admired by figures as diverse as Gaiman, Borges,

Last week, in a post about Neil Gaiman’s Sandman, I said that certain habits of Gaiman’s plotting reminded me of G.K. Chesterton. It seemed to me that I’d referred to Chesterton fairly often in my posts here, so I did a search of the Black Gate archive. I found that I had in fact mentioned Chesterton a number of times, but that neither I nor anyone else had yet written a post for Black Gate specifically about him or any of his works. I’ve therefore put together this piece to give an overview of the man and his writing. It’s insufficient; Chesterton’s difficult to describe, more so than most writers. But one has to begin somewhere. He’s an important early fantasist, admired by figures as diverse as Gaiman, Borges,  There’s a certain kind of structure I’ve lately begun to notice in certain novels. These books read like puzzles, telling one story directly and overtly while implying a second story, or highly variant reading of the first story, through carefully-placed gaps, contradictions, and seemingly-irrelevant details. Throwaway references in highly-disparate points of the book might imply a completely different way to read at least the plot and often the tone or theme. It’s something Gene Wolfe does a lot; other examples I’ve noticed lately are

There’s a certain kind of structure I’ve lately begun to notice in certain novels. These books read like puzzles, telling one story directly and overtly while implying a second story, or highly variant reading of the first story, through carefully-placed gaps, contradictions, and seemingly-irrelevant details. Throwaway references in highly-disparate points of the book might imply a completely different way to read at least the plot and often the tone or theme. It’s something Gene Wolfe does a lot; other examples I’ve noticed lately are