“All Folk Cherished Their Legends”: Phyllis Ann Karr’s Wildraith’s Last Battle

A little while ago, I wrote here about Phyllis Ann Karr’s 1986 novel At Amberleaf Fair. I thought it was well-written and inventive, quietly doing highly distinctive things with the fantasy genre without drawing attention to its own originality. I recently read another book by Karr, 1982’s Wildwraith’s Last Battle, and found it was different from Amberleaf Fair while also sharing many of its virtues: tight prose, clever plotting, a strong sense of character, and a tremendously well-constructed setting. It’s not a perfect book, but it’s well worth discussing here.

A little while ago, I wrote here about Phyllis Ann Karr’s 1986 novel At Amberleaf Fair. I thought it was well-written and inventive, quietly doing highly distinctive things with the fantasy genre without drawing attention to its own originality. I recently read another book by Karr, 1982’s Wildwraith’s Last Battle, and found it was different from Amberleaf Fair while also sharing many of its virtues: tight prose, clever plotting, a strong sense of character, and a tremendously well-constructed setting. It’s not a perfect book, but it’s well worth discussing here.

Set in the southern hemisphere of an unknown world, a group of iron-age nations have begun a complex three-sided war. Meanwhile, for reasons unrelated to the war, one woman loses everything and curses the god, Wildrava, that she believes is responsible. The result is that the god incarnates as a (more-or-less) human female named Wildraith and tries to seek out the woman who cursed her — but the woman, Ylsa, is finding her own way among the shifting sides of the ongoing war. Despite herself, Wildraith finds herself becoming a key player in the war as she strives to find Ylsa and break the curse.

The book is, to use recently-developed terminology, both grim and dark. Violence, including sexual violence and torture, is an element of the story’s reality and occasionally described in detail. There’s nothing ostentatious in the novel’s depiction of violence, though, nothing exploitative or false. It’s a part of the tone and world and feels earned without forcing the whole book into depressive bleakness. Ultimately, what makes the novel remarkable is its ability to fuse matter-of-fact description of day-to-day activities with the experience of war and also a distinctively fantastic sense of wonder: a feeling of the numinous that comes from gods involving themselves in the affairs of mortals.

In 1984, writer Jan Morris spent several months in Hav, an idiosyncratic city in the Eastern Mediterranean. She left it just ahead of a violent insurrection and collected her letters describing the city into a book, Last Letters From Hav. Twenty years later, she returned to Hav to document what had changed, in a piece called Hav of the Myrmidons. Both were collected together in one volume, called simply Hav.

In 1984, writer Jan Morris spent several months in Hav, an idiosyncratic city in the Eastern Mediterranean. She left it just ahead of a violent insurrection and collected her letters describing the city into a book, Last Letters From Hav. Twenty years later, she returned to Hav to document what had changed, in a piece called Hav of the Myrmidons. Both were collected together in one volume, called simply Hav. Every so often, I come across a book so idiosyncratic I have to write about it just to work out what it is I’ve read. A book strange and powerful, but whose power is difficult to locate or specify. Sometimes it’s hard even to be sure whether the book can be called ‘good’ in any meaningful way. By writing about it, I can get some thoughts in order, and see where they lead. And as such, I want to take a look here at Olga Slavnikova’s 2017.

Every so often, I come across a book so idiosyncratic I have to write about it just to work out what it is I’ve read. A book strange and powerful, but whose power is difficult to locate or specify. Sometimes it’s hard even to be sure whether the book can be called ‘good’ in any meaningful way. By writing about it, I can get some thoughts in order, and see where they lead. And as such, I want to take a look here at Olga Slavnikova’s 2017. V.E. Schwab had written a number of YA novels when, in 2013, Tor published her book Vicious. Billed by some as a super-hero story, it had elements of that genre while also, to some extent, questioning its assumptions. Reading it, I found that the book seemed interested in questions of morality, heroism, and villainy, but that the super-hero aspects were so attenuated I doubt it would have occurred to me to consider it as a super-hero story without the claims of the book jacket. Its handling of ideas of heroism felt like a reiteration of themes comics (Marvel, DC, and independent) have been interrogating relentlessly (if not neurotically) for at least thirty years. In some ways, it’s best to simply ignore the ‘super-hero’ tag. If you do, you’re left with a well-paced and sharply-structured novel. And on its own terms, it’s an enjoyable tale.

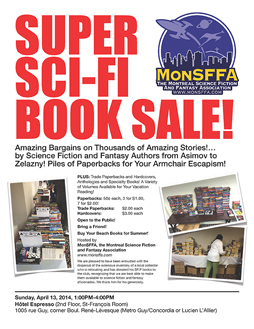

V.E. Schwab had written a number of YA novels when, in 2013, Tor published her book Vicious. Billed by some as a super-hero story, it had elements of that genre while also, to some extent, questioning its assumptions. Reading it, I found that the book seemed interested in questions of morality, heroism, and villainy, but that the super-hero aspects were so attenuated I doubt it would have occurred to me to consider it as a super-hero story without the claims of the book jacket. Its handling of ideas of heroism felt like a reiteration of themes comics (Marvel, DC, and independent) have been interrogating relentlessly (if not neurotically) for at least thirty years. In some ways, it’s best to simply ignore the ‘super-hero’ tag. If you do, you’re left with a well-paced and sharply-structured novel. And on its own terms, it’s an enjoyable tale. Leaving the dark brick stairwells of the Lucien L’Allier métro last Sunday morning at 10, we found the rain was holding off: something not to be expected. Forecasts called for meteorological chaos in Montréal over the following days. Up to 24 degrees celsius, down to 2, thunderstorms, snow. But that was in the future. For the moment, Grace and I were looking for books to hold us through those unsettled days and more.

Leaving the dark brick stairwells of the Lucien L’Allier métro last Sunday morning at 10, we found the rain was holding off: something not to be expected. Forecasts called for meteorological chaos in Montréal over the following days. Up to 24 degrees celsius, down to 2, thunderstorms, snow. But that was in the future. For the moment, Grace and I were looking for books to hold us through those unsettled days and more. A little while ago, I stumbled on a book that seemed especially worth writing about here: The City, by Stella Gemmell. It’s Gemmell’s first solo novel; she also completed Troy: Fall of Kings, the last book by her late husband, David. David Gemmell was a widely-known heroic fantasy writer — those unfamiliar with his work can see

A little while ago, I stumbled on a book that seemed especially worth writing about here: The City, by Stella Gemmell. It’s Gemmell’s first solo novel; she also completed Troy: Fall of Kings, the last book by her late husband, David. David Gemmell was a widely-known heroic fantasy writer — those unfamiliar with his work can see  Two years ago, veteran author Mary Gentle’s most recent novel The Black Opera was published to mixed reviews. Some liked the book’s mix of alternate-history fantasy and comic-opera theatricality — as the sub-title has it, “a novel of Opera, Volcanoes, and the Mind of God.” Others,

Two years ago, veteran author Mary Gentle’s most recent novel The Black Opera was published to mixed reviews. Some liked the book’s mix of alternate-history fantasy and comic-opera theatricality — as the sub-title has it, “a novel of Opera, Volcanoes, and the Mind of God.” Others,  Somewhere in Europe, probably around the end of the 13th or the beginning of the 14th century, someone put together a book of tales. Likely this someone was a cleric who wanted to compile a manual to use in sermons and preaching. The texts were written in Latin and featured stories of all sorts: romances, travellers’ tales, fragments of Pliny and Herodotus and Aesop. A number were brief and didactic, if not prosaic, describing some uninteresting event or propounding a riddle a nearby wise man quickly answered with too pat an explanation — but others of the tales were filled with miracles and adventure and magic, with angels and saints and knights and dragons. Each was given a detailed moral, with every incident and character shown to have allegorical significance. Whether because it boasted wonder-stories, because it made those wonder-stories Christian parables, or both, the book quickly became immensely popular. This being well before the age of print, manuscripts proliferated, gaining and losing stories along the way.

Somewhere in Europe, probably around the end of the 13th or the beginning of the 14th century, someone put together a book of tales. Likely this someone was a cleric who wanted to compile a manual to use in sermons and preaching. The texts were written in Latin and featured stories of all sorts: romances, travellers’ tales, fragments of Pliny and Herodotus and Aesop. A number were brief and didactic, if not prosaic, describing some uninteresting event or propounding a riddle a nearby wise man quickly answered with too pat an explanation — but others of the tales were filled with miracles and adventure and magic, with angels and saints and knights and dragons. Each was given a detailed moral, with every incident and character shown to have allegorical significance. Whether because it boasted wonder-stories, because it made those wonder-stories Christian parables, or both, the book quickly became immensely popular. This being well before the age of print, manuscripts proliferated, gaining and losing stories along the way. Amos Tutuola was born in Nigeria in 1920 to a Christian family. With six years of formal schooling, he served as a coppersmith with the Lagos-based arm of the Royal Air Force in World War Two, then worked at a number of of odd jobs. As he tells it, a government magazine he happened to read, with “very lovely portraits of the gods,” advertised books based on Yoruba legends. Tutuola remembered being praised as a storyteller in school and decided there was no reason he shouldn’t turn his hand to writing similar books. So he did. He completed his first book, The Palm-Wine Drinkard, in only a few days.

Amos Tutuola was born in Nigeria in 1920 to a Christian family. With six years of formal schooling, he served as a coppersmith with the Lagos-based arm of the Royal Air Force in World War Two, then worked at a number of of odd jobs. As he tells it, a government magazine he happened to read, with “very lovely portraits of the gods,” advertised books based on Yoruba legends. Tutuola remembered being praised as a storyteller in school and decided there was no reason he shouldn’t turn his hand to writing similar books. So he did. He completed his first book, The Palm-Wine Drinkard, in only a few days. With

With