My Fantasia Festival, Day 2: Kite and Open Windows

On Friday night, the cats came out at Fantasia.

On Friday night, the cats came out at Fantasia.

They may have been around on Thursday, too, but this was the first I’d heard them this year. It’s one of the traditions that’ve sprung up at Fantasia: some years ago a series of short films called Simon’s Cat fostered an outbreak of meows among the audience (or, for the francophones, miaous). Somehow it spread to the rest of the festival. And then returned the next year. So, now, when the lights go down for a film — but before anything starts playing on the screen — you’ll hear the audience calling out meows. And the occasional ‘woof’ or ‘baa,’ just for variety.

Friday night, I saw two films welcomed by meows. Kite, a bloody near-future sf film, played at 6:35 in the big Hall Theatre, preceded by a short comedy, Raging Balls of Steel Justice. Then I headed downstairs to the D.B. Clarke Theatre to catch a twisty thriller called Open Windows. I don’t think either feature was entirely successful, but both qualified as ‘interesting,’ the latter rather more than the former.

Let’s begin with the short. Steel Justice is a violent, raunchy parody of 80s action movies, done in claymation. A Sledge Hammer!-style supercop and his horny robot sidekick have to save a prominent banker who’s been kidnapped by a barn full of escaped convicts. Much carnage ensues. It’s quick, fluidly animated, and extremely gross. As the saying goes: people who like this sort of thing will find this the sort of thing they like. The humour wasn’t quite to my taste, and it did feel quite a lot like the aforementioned Sledge Hammer! without network content guidelines. For some, that’ll be enough to make it different; as it happens, not for me. At any rate, what it does, it does competently.

Last night’s opening film at the seventeenth

Last night’s opening film at the seventeenth  Sylvia Townsend Warner is probably best known in fantasy circles for The Kingdoms of Elfin, her collection of linked short stories from 1977. I’ve been looking for a copy of that book, but have yet to locate one (using the Internet, I firmly feel, is cheating). But I did recently come across her debut novel, 1926’s Lolly Willowes, or the Loving Huntsman. It’s been described as a deal-with-the-devil story in which a middle-aged Englishwoman makes a Satanic pact and becomes a witch. That’s accurate, but not necessarily the best description.

Sylvia Townsend Warner is probably best known in fantasy circles for The Kingdoms of Elfin, her collection of linked short stories from 1977. I’ve been looking for a copy of that book, but have yet to locate one (using the Internet, I firmly feel, is cheating). But I did recently come across her debut novel, 1926’s Lolly Willowes, or the Loving Huntsman. It’s been described as a deal-with-the-devil story in which a middle-aged Englishwoman makes a Satanic pact and becomes a witch. That’s accurate, but not necessarily the best description. There was an extended period of time in the 1990s and the first decade of this century when I didn’t read much science fiction or genre fantasy. I started reacquainting myself with these fields a few years ago and I’m still in the process of learning what I missed. It’s not uncommon for me to only now find out about an author who established themselves during those years. Which brings me around to Pat Murphy.

There was an extended period of time in the 1990s and the first decade of this century when I didn’t read much science fiction or genre fantasy. I started reacquainting myself with these fields a few years ago and I’m still in the process of learning what I missed. It’s not uncommon for me to only now find out about an author who established themselves during those years. Which brings me around to Pat Murphy. Browsing about the Internet recently, I stumbled on something that interested me. Several things, actually. Specifically, the results at the

Browsing about the Internet recently, I stumbled on something that interested me. Several things, actually. Specifically, the results at the  Lately in this space I seem to be writing a lot,

Lately in this space I seem to be writing a lot,  There’s a suspicion common in genre circles when a writer or creator from ‘the mainstream’ uses genre conventions or plot points. It’s sometimes a justified suspicion, as the writer unfamiliar with genre falls into cliché or loses control of their material through inexperience with the form. But sometimes something else happens: fresh eyes can find new truths. And every so often somebody approaching a genre by starting at square one can show why the classic genre material works in the first place — and even twist that material a bit to find new life for it going forward.

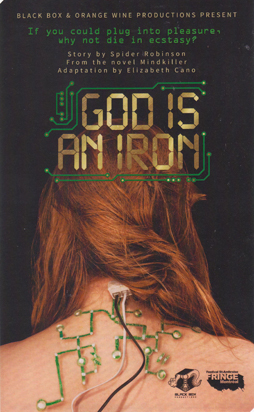

There’s a suspicion common in genre circles when a writer or creator from ‘the mainstream’ uses genre conventions or plot points. It’s sometimes a justified suspicion, as the writer unfamiliar with genre falls into cliché or loses control of their material through inexperience with the form. But sometimes something else happens: fresh eyes can find new truths. And every so often somebody approaching a genre by starting at square one can show why the classic genre material works in the first place — and even twist that material a bit to find new life for it going forward. Monday, June 16, I went to see a show at the

Monday, June 16, I went to see a show at the  One of the interesting things about going back to the beginning of any tradition is seeing how things might have gone. Seeing, that is, possibilities unexplored and roads not taken. Sometimes you catch a glimpse of what, in retrospect, is an earlier stage of evolution. Sometimes there’s a sense of a missed chance. And then sometimes you can see why things went the way they did.

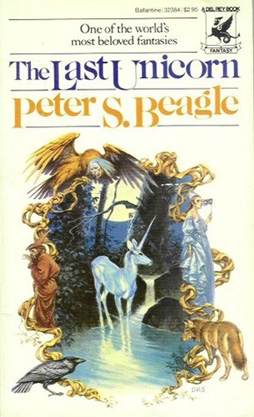

One of the interesting things about going back to the beginning of any tradition is seeing how things might have gone. Seeing, that is, possibilities unexplored and roads not taken. Sometimes you catch a glimpse of what, in retrospect, is an earlier stage of evolution. Sometimes there’s a sense of a missed chance. And then sometimes you can see why things went the way they did. In 1962, Peter S. Beagle began writing a fantasy novel he called The Last Unicorn. Published in 1968, the book was both serious and whimsical, a kind of extended fable about a unicorn who found she was the last of her kind and adventured through a medieval fantasyland, possibly Irish and possibly not, in search of the wicked king holding all other unicorns captive. The tone embraced both the comic (one of the major characters is an incompetent magician named Schmendrick) and the dreamlike (as in the terrifying Red Bull who emerges as a crucial antagonist). The book’s a tremendous accomplishment, a vivid working-out of classic fantasy themes.

In 1962, Peter S. Beagle began writing a fantasy novel he called The Last Unicorn. Published in 1968, the book was both serious and whimsical, a kind of extended fable about a unicorn who found she was the last of her kind and adventured through a medieval fantasyland, possibly Irish and possibly not, in search of the wicked king holding all other unicorns captive. The tone embraced both the comic (one of the major characters is an incompetent magician named Schmendrick) and the dreamlike (as in the terrifying Red Bull who emerges as a crucial antagonist). The book’s a tremendous accomplishment, a vivid working-out of classic fantasy themes.