Fantasia Diary 2015, Day 5: Teana: 10000 Years Later, Crimson Whale, and The Shamer’s Daughter

One of the things people don’t tell you about getting older is that the more books you read and movies you see, the more likely you are to see those stories echoed in other stories. The new books and movies you come across remind to you of the older books and movies you already know. Sometimes there’s good reason for that, as artists try to engage in a dialogue with their forebears. Sometimes you’re just seeing things.

One of the things people don’t tell you about getting older is that the more books you read and movies you see, the more likely you are to see those stories echoed in other stories. The new books and movies you come across remind to you of the older books and movies you already know. Sometimes there’s good reason for that, as artists try to engage in a dialogue with their forebears. Sometimes you’re just seeing things.

Saturday, July 25, was an interesting series of riddles for me at the Fantasia Festival. I saw three movies that day. Teana: 10000 Years Later is a high science-fantasy 3D CGI animated film from China. Crimson Whale is a traditionally-animated post-apocalypse fable from South Korea. And Denmark’s The Shamer’s Daughter is a live-action adaptation of the first volume of a Danish YA high fantasy. I enjoyed all of them, and saw what seemed to be nods to familiar works within each — though in some cases that might be my imagination running away with me.

Let’s start with Teana (AKA 10000 Years Later, originally Yi wan nian yi hou), which screened at the large Hall Theatre. It’s one of the most visually spectacular movies I’ve seen at Fantasia. Bursting with colour and invention, it moves quickly, introduces a ton of characters, creates a world, and tells an epic story with some very pointed social commentary. I’ve seen some mention online that it’s based on a Tibetan fable, but can find no more specific information than that. Personally, I found myself strongly reminded of The Lord of the Rings, as the film seemed to refer to Tolkien while also inverting certain aspects of his story.

Late last Friday night, the 17th of July (or early the next morning, to be precise), I was unable to keep from smiling as

Late last Friday night, the 17th of July (or early the next morning, to be precise), I was unable to keep from smiling as  In the days leading up to the Fantasia Festival I’d look at the schedule and see a dilemma looming on the second day, last Wednesday. The first of many similar dilemmas ahead: which of two movies playing directly opposite each other do I watch? In this case a French suspense film, Un homme idéal (in English A Perfect Man), was up against a Donnie Yen martial-arts movie, Kung Fu Killer. The next day would be simpler, as my girlfriend and I had agreed to see the Japanese teen drama Wonderful World End together. But Wednesday offered two very different things. Which to watch?

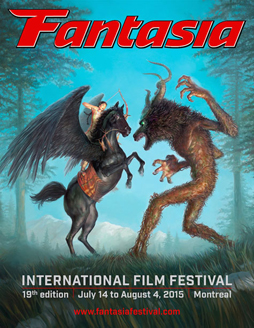

In the days leading up to the Fantasia Festival I’d look at the schedule and see a dilemma looming on the second day, last Wednesday. The first of many similar dilemmas ahead: which of two movies playing directly opposite each other do I watch? In this case a French suspense film, Un homme idéal (in English A Perfect Man), was up against a Donnie Yen martial-arts movie, Kung Fu Killer. The next day would be simpler, as my girlfriend and I had agreed to see the Japanese teen drama Wonderful World End together. But Wednesday offered two very different things. Which to watch? The Fantasia International Film Festival opened in Montreal on Tuesday night, and this year, like last year, I’ll be covering it for Black Gate. This will be the 19th edition of Fantasia, one of the world’s largest genre-oriented film festivals, and I’m looking forward to seeing a lot of movies. As I did last time, I’m planning to keep a diary-style record discussing the films I see and also recapping some of the special events around them — a lot of screenings are accompanied by presentations, or by discussions with the creators, and I’ll pass along my notes on those.

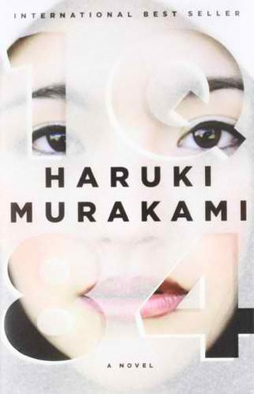

The Fantasia International Film Festival opened in Montreal on Tuesday night, and this year, like last year, I’ll be covering it for Black Gate. This will be the 19th edition of Fantasia, one of the world’s largest genre-oriented film festivals, and I’m looking forward to seeing a lot of movies. As I did last time, I’m planning to keep a diary-style record discussing the films I see and also recapping some of the special events around them — a lot of screenings are accompanied by presentations, or by discussions with the creators, and I’ll pass along my notes on those. The first two books of Haruki Murakami’s 1Q84 were published in Japan in 2009, with the third following in 2010. Plans for a one-volume English edition were soon underway, with the first two books translated by Jay Rubin and the third, due to time pressures, by J. Philip Gabriel. The complete English edition, running over 900 pages despite the editing-out of some extended recap passages in the third book, appeared in 2011.

The first two books of Haruki Murakami’s 1Q84 were published in Japan in 2009, with the third following in 2010. Plans for a one-volume English edition were soon underway, with the first two books translated by Jay Rubin and the third, due to time pressures, by J. Philip Gabriel. The complete English edition, running over 900 pages despite the editing-out of some extended recap passages in the third book, appeared in 2011. In some ways Salman Rushdie’s 2008 novel The Enchantress of Florence feels like a classic pulp fantasy entertainment. A bit less than a hundred years ago you could find a lot of pulp set in India, central Asia, and the Middle East: Harold Lamb recounting colourful histories of the great Mongol conquerors and Timur-Leng; Fritz Leiber imagining a pair of sword-wielding comrades

In some ways Salman Rushdie’s 2008 novel The Enchantress of Florence feels like a classic pulp fantasy entertainment. A bit less than a hundred years ago you could find a lot of pulp set in India, central Asia, and the Middle East: Harold Lamb recounting colourful histories of the great Mongol conquerors and Timur-Leng; Fritz Leiber imagining a pair of sword-wielding comrades  In 2007 Annick Press published a Young Adult tale called The Night Wanderer: A Native Gothic Novel by Drew Hayden Taylor, a veteran playwright, journalist, and essayist (as well as stand-up comic, TV writer, and documentary film-maker). The book follows a mysterious stranger who returns from Europe to the fictional Anishinabe (or Ojibway) Otter Lake Reserve in what is now Ontario, and a teenage girl whose life he ends up affecting. Taylor mentions in an afterword that the story began existence as a play which never quite satisfied him, until fifteen years later, while working with Annick Press on another project, he rewrote it as a prose novel. It’s since been adapted by Alison Kooistra into a graphic novel with art by Mike Wyatt.

In 2007 Annick Press published a Young Adult tale called The Night Wanderer: A Native Gothic Novel by Drew Hayden Taylor, a veteran playwright, journalist, and essayist (as well as stand-up comic, TV writer, and documentary film-maker). The book follows a mysterious stranger who returns from Europe to the fictional Anishinabe (or Ojibway) Otter Lake Reserve in what is now Ontario, and a teenage girl whose life he ends up affecting. Taylor mentions in an afterword that the story began existence as a play which never quite satisfied him, until fifteen years later, while working with Annick Press on another project, he rewrote it as a prose novel. It’s since been adapted by Alison Kooistra into a graphic novel with art by Mike Wyatt. Darcy Tamayose’s novel Odori was published in 2007, and in 2008 won the Canada Council of the Arts’ Canada-Japan Literary Award for an English-language book. Lush yet understated, Odori uses dreams, ghosts, and the fantastic to frame the story of a woman’s life, told across generations. I think more than most books, it can profitably read in a number of ways; but what for me is most striking is its approach to storytelling and the layering of tales.

Darcy Tamayose’s novel Odori was published in 2007, and in 2008 won the Canada Council of the Arts’ Canada-Japan Literary Award for an English-language book. Lush yet understated, Odori uses dreams, ghosts, and the fantastic to frame the story of a woman’s life, told across generations. I think more than most books, it can profitably read in a number of ways; but what for me is most striking is its approach to storytelling and the layering of tales. Yangsze Choo’s 2013 book The Ghost Bride starts out very much like a gothic novel. Li Lan, the beautiful young daughter of an impoverished scholar in the Chinese community of Malacca in the year 1893, draws a sinister marriage proposal from the rich and powerful Lim family: a ceremonial spirit marriage to Lim Tian Ching, the recently-deceased heir to the Lim wealth. But Li Lan finds herself drawn to Tian Ching’s cousin, Lim Tian Bai — and then Tian Ching begins to appear in her dreams, eager for their upcoming nuptials. She tries to exorcise him, and then what started as a gothic becomes broader and stranger. Li Lan enters a world of ghosts where she uncovers hints of corruption among the judges of hell, and then must undertake a quest into a further and yet more fantastical world, a Campbellian hero(ine)’s journey of dangers and guardian allies and magic items.

Yangsze Choo’s 2013 book The Ghost Bride starts out very much like a gothic novel. Li Lan, the beautiful young daughter of an impoverished scholar in the Chinese community of Malacca in the year 1893, draws a sinister marriage proposal from the rich and powerful Lim family: a ceremonial spirit marriage to Lim Tian Ching, the recently-deceased heir to the Lim wealth. But Li Lan finds herself drawn to Tian Ching’s cousin, Lim Tian Bai — and then Tian Ching begins to appear in her dreams, eager for their upcoming nuptials. She tries to exorcise him, and then what started as a gothic becomes broader and stranger. Li Lan enters a world of ghosts where she uncovers hints of corruption among the judges of hell, and then must undertake a quest into a further and yet more fantastical world, a Campbellian hero(ine)’s journey of dangers and guardian allies and magic items.  Early in 2013 I wrote

Early in 2013 I wrote