Plasticity of Vision: Ben Okri’s Famished Road Cycle

Ben Okri’s 1991 novel The Famished Road won the Booker Prize and was followed in 1993 by Songs of Enchantment and in 1998 by Infinite Riches. Riches called itself “Volume Three of The Famished Road cycle,” which seems an apt term. The books individually are visionary accomplishments, filled with ecstatic and elegant prose; and they are concerned with cycles, of lives and stories. They are concerned with myth, and themselves create myth, a mythology of history or at least a mythology intersecting with history.

Ben Okri’s 1991 novel The Famished Road won the Booker Prize and was followed in 1993 by Songs of Enchantment and in 1998 by Infinite Riches. Riches called itself “Volume Three of The Famished Road cycle,” which seems an apt term. The books individually are visionary accomplishments, filled with ecstatic and elegant prose; and they are concerned with cycles, of lives and stories. They are concerned with myth, and themselves create myth, a mythology of history or at least a mythology intersecting with history.

They follow Azaro, whose name is short for ‘Lazarus.’ He is an abiku, a spirit child, in what appears to be pre-independence Nigeria (the country where the books take place are never named). Abiku, we are told, are supposed to be born many times, dying young repeatedly; Azaro has decided to stay in this world, but can see spirits and in fact remembers his existence before birth. His friends in the spirit world remember him, too, and want him back. The first book in particular revolves around his determination to stay with the family into which he has been born, and his desire to make his mother happy. The second book, as Azaro himself observes, changes focus; it is less about his struggles with the other world, as his spirit friends change tack: “They chose to draw me deeper into the horrors of existence as a way of forcing me to recoil from life.” The focus here moves away from Abiku, toward his parents and his ghetto community; by the third book we are caught up in their myth, following their story as it moves on toward the end of its cycle.

The books are about, among other things, story and history and the ending of one cycle in a people’s existence and the beginning of a new. They are about the creation of a new nation. Are they fantasies? I suppose it’s mostly possible to read them as realistic — to see Azaro as delusional, to dismiss all the myths and visions as unreal. I am wildly skeptical that such an approach would produce any useful understanding of the books. On the other hand, these books are involved with myth as opposed to the kind of writing normally described by the word “fantasy.” Personally, I’d describe them as fantasies because to me “fantasy” includes the visionary — which these books are, 1990s equivalent to the prophecies of William Blake. It’s fair to argue that I’m getting those words backwards, that fantasy is a subspecies of the visionary instead of the reverse; but I think that “fantasy” perhaps also implies the kind of creative response demanded here of readers. As I said, I don’t think approaching these books with a perspective that privileges the realistic will get very far. Whatever world you use for them, it’s worth acknowledging that these are books of myth that call out to the mythic sensibility.

Time flies when you’re having fun. My

Time flies when you’re having fun. My  With my Fantasia coverage done for another year, I thought I’d write a final post looking back over what I saw to try to make sense of it all. And to talk about why I’ve done what I’ve done.

With my Fantasia coverage done for another year, I thought I’d write a final post looking back over what I saw to try to make sense of it all. And to talk about why I’ve done what I’ve done. Concluding my discussion of films I saw courtesy of the Fantasia screening room, I’ll be writing today about three movies: a drama with elements of horror called They Look Like People, the horror-comedy called Nina Forever, and one of the purest horror movies I’ve ever seen, Nathan Ambrosioni’s Hostile. I’ll begin with They Look Like People, written and directed by Perry Blackshear. It’s about two men, one of whom, Wyatt (MacLeod Andrews), appears to be falling into insanity; he believes aliens are giving him messages. He happens to cross paths with his old friend Christian (Evan Dumouchel). They’ve both recently had long-term relationships fall apart — Wyatt’s fiancée in fact cheated on him and then broke up with him. Christian offers Wyatt a place to stay, and Wyatt accepts.

Concluding my discussion of films I saw courtesy of the Fantasia screening room, I’ll be writing today about three movies: a drama with elements of horror called They Look Like People, the horror-comedy called Nina Forever, and one of the purest horror movies I’ve ever seen, Nathan Ambrosioni’s Hostile. I’ll begin with They Look Like People, written and directed by Perry Blackshear. It’s about two men, one of whom, Wyatt (MacLeod Andrews), appears to be falling into insanity; he believes aliens are giving him messages. He happens to cross paths with his old friend Christian (Evan Dumouchel). They’ve both recently had long-term relationships fall apart — Wyatt’s fiancée in fact cheated on him and then broke up with him. Christian offers Wyatt a place to stay, and Wyatt accepts. By this point I’ve discussed all the movies I saw in theatres at the Fantasia film festival, but there remain a half-dozen more that I saw courtesy of the Fantasia screening room. I’m going to write about them over two posts, for ease of reading. And then I’ll have a coda wrapping up my Fantasia coverage with thoughts on what I saw, and the value of the festival. For now: reviews of the psychological romance comedy Poison Berry in My Brain, the metafictional satire Anima State, and the suspense movie The Interior. All of them, one way or another, directly to do with what happens inside the head.

By this point I’ve discussed all the movies I saw in theatres at the Fantasia film festival, but there remain a half-dozen more that I saw courtesy of the Fantasia screening room. I’m going to write about them over two posts, for ease of reading. And then I’ll have a coda wrapping up my Fantasia coverage with thoughts on what I saw, and the value of the festival. For now: reviews of the psychological romance comedy Poison Berry in My Brain, the metafictional satire Anima State, and the suspense movie The Interior. All of them, one way or another, directly to do with what happens inside the head. Tuesday, August 4, was my last day at the Fantasia Festival. It was the official closing day of Fantasia; they’d added a few screenings on Wednesday, but nothing that looked compelling to me. I have some more films to write about after this, thanks to the festival’s screening room. But since I’ll be writing here about the last three movies I saw in a theatre at the 2015 Fantasia Festival, in this post I want to make a point of acknowledging the crowds.

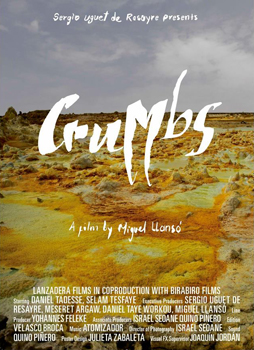

Tuesday, August 4, was my last day at the Fantasia Festival. It was the official closing day of Fantasia; they’d added a few screenings on Wednesday, but nothing that looked compelling to me. I have some more films to write about after this, thanks to the festival’s screening room. But since I’ll be writing here about the last three movies I saw in a theatre at the 2015 Fantasia Festival, in this post I want to make a point of acknowledging the crowds. Fantasia was beginning to wind down. After seeing five movies on Sunday, August 2, I only saw four on Monday the 3rd: an Ethiopian post-apocalypse quest called Crumbs; a Spanish crime movie called Marshland; an American suspense movie called The Invitation; and a French science fiction comedy called Cosmodrama. I’d heard good things about each of these movies, and I had cautiously high hopes. Which were mostly fulfilled.

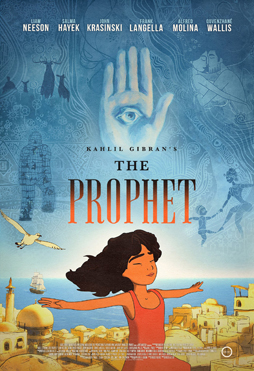

Fantasia was beginning to wind down. After seeing five movies on Sunday, August 2, I only saw four on Monday the 3rd: an Ethiopian post-apocalypse quest called Crumbs; a Spanish crime movie called Marshland; an American suspense movie called The Invitation; and a French science fiction comedy called Cosmodrama. I’d heard good things about each of these movies, and I had cautiously high hopes. Which were mostly fulfilled. Sunday, August 2, was a day I’d been waiting for and slightly dreading. I was planning to see five films, one after the other. All of them at the large Hall Theatre, except for the second, a presentation of short animated films at the De Sève. It would kick off at 12:30 with Kahlil Gibran’s The Prophet, a cartoon adaptation of the classic book. The Outer Limits of Animation 2015 showcase would follow. Then Experimenter, a biopic about controversial psychologist Stanley Milgram, he of the notorious fake electroshock experiments. Then Ninja the Monster — as its title suggests, a film about a confrontation between a ninja and a monster. Finally would come Strayer’s Chronicle, a novel adaptation about a group of alienated teenagers with strange powers fighting to protect a world that hates and fears them. I was fairly sure it was possible to make a good movie out of that sort of material. But I had a lot of film to watch before I’d get to see it.

Sunday, August 2, was a day I’d been waiting for and slightly dreading. I was planning to see five films, one after the other. All of them at the large Hall Theatre, except for the second, a presentation of short animated films at the De Sève. It would kick off at 12:30 with Kahlil Gibran’s The Prophet, a cartoon adaptation of the classic book. The Outer Limits of Animation 2015 showcase would follow. Then Experimenter, a biopic about controversial psychologist Stanley Milgram, he of the notorious fake electroshock experiments. Then Ninja the Monster — as its title suggests, a film about a confrontation between a ninja and a monster. Finally would come Strayer’s Chronicle, a novel adaptation about a group of alienated teenagers with strange powers fighting to protect a world that hates and fears them. I was fairly sure it was possible to make a good movie out of that sort of material. But I had a lot of film to watch before I’d get to see it. Saturday, August 1, would start early for me at Fantasia. At 12:30 I was seeing a Chinese fantasy adventure called Snow Girl and the Dark Crystal. Then I’d head over to the screening room, where I planned to watch a documentary about the Turkish film industry, Remix, Remake, Ripoff: About Copy Culture and Turkish Pop Cinema. Then I’d go to the De Sève Theatre for a pair of films, the post-apocalypse art-house movie Orion and then the Korean drama Socialphobia. Once again, a nice varied day.

Saturday, August 1, would start early for me at Fantasia. At 12:30 I was seeing a Chinese fantasy adventure called Snow Girl and the Dark Crystal. Then I’d head over to the screening room, where I planned to watch a documentary about the Turkish film industry, Remix, Remake, Ripoff: About Copy Culture and Turkish Pop Cinema. Then I’d go to the De Sève Theatre for a pair of films, the post-apocalypse art-house movie Orion and then the Korean drama Socialphobia. Once again, a nice varied day. Friday, July 31, started late for me at Fantasia. My first movie, a horror-comedy called Ava’s Possessions, screened at the Hall Theatre at 5:15. After that I decided to watch the Indonesian wuxia movie The Golden Cane Warrior. Then I’d go across to the De Sève Theatre to catch the surreal science-fictional American-Argentinian movie H. before returning to the Hall for the Friday midnight movie, a Quebec-made tribute to 80s post-apocalypse action movies called Turbo Kid. That would carry me through to something like 2 AM. So if things started late, at least it looked like I had a lot on the agenda.

Friday, July 31, started late for me at Fantasia. My first movie, a horror-comedy called Ava’s Possessions, screened at the Hall Theatre at 5:15. After that I decided to watch the Indonesian wuxia movie The Golden Cane Warrior. Then I’d go across to the De Sève Theatre to catch the surreal science-fictional American-Argentinian movie H. before returning to the Hall for the Friday midnight movie, a Quebec-made tribute to 80s post-apocalypse action movies called Turbo Kid. That would carry me through to something like 2 AM. So if things started late, at least it looked like I had a lot on the agenda.