Noise About Xignals

I took a break from cutting the grass around the house. It was a hot day, and the chore always took a while. “Look what I found,” my aunt greeted me, as I went indoors and dropped into a chair. She’d been cleaning up, preparing to move into the cottage, and she’d been discovering things tucked away and forgotten long before, as one does. She handed me a copy of Xignals.

I took a break from cutting the grass around the house. It was a hot day, and the chore always took a while. “Look what I found,” my aunt greeted me, as I went indoors and dropped into a chair. She’d been cleaning up, preparing to move into the cottage, and she’d been discovering things tucked away and forgotten long before, as one does. She handed me a copy of Xignals.

Years ago, back in the twentieth century, Xignals had been the in-house newsletter of Waldenbooks’ Otherworlds Club, a buyers’ club program for science fiction and fantasy readers. I was never a member, but I’d pick up a copy of Xignals when I’d go with my aunt and grandparents over the border from their summer cottage in Philipsburg, Quebec, to have dinner in Burlington, Vermont. There was a Waldenbooks in one of the shopping malls in Burlington, where we’d stop after eating, and I’d take an inexcusably long time browsing the science fiction section before buying a book to take back to Philipsburg. And, often, grab a copy of Xignals with it.

In 2016 I sat and read this copy of Xignals for perhaps the first time in over twenty-five years. It was dated August/September 1988, which means it had come out as I was turning 15. It was a 16-page booklet, 8 sheets of 11-by-17-inch paper folded over, black and white with greyscale images and green lines and fills. I was fascinated by the thing, its edges nibbled by field mice seeking a home during some winter between 1988 and 2016. It brought to my mind not a rush of Proustian reminiscence, but a sense of significance in difference. I was made conscious of the way the future was conceived then, based on the way the world then operated, and the way the world operates differently now.

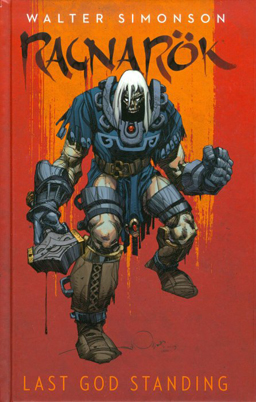

Walt Simonson’s published eight issues so far of his ongoing comics series Ragnarök, along with a trade paperback collecting issues 1 through 6. Simonson, a veteran master of the comics form, is joined for the book by colorist Laura Martin and letterer John Workman. Edited by Scott Dunbier, Ragnarök’s published through IDW, and Chris Mowry’s credited with “production” on the first seven issues while Neil Uyetake gets the production credit on the eighth. What is Ragnarök beyond that? A fast-paced, adventurous saga. A grim playing-about with Norse myth. A super-hero high fantasy that nods to the past while telling a new and distinctive tale. And: a comic as exuberant as it is well-crafted.

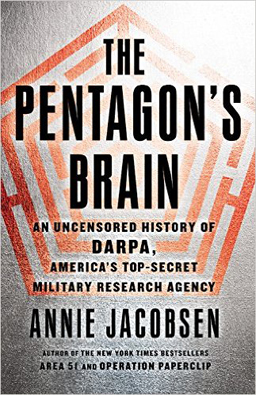

Walt Simonson’s published eight issues so far of his ongoing comics series Ragnarök, along with a trade paperback collecting issues 1 through 6. Simonson, a veteran master of the comics form, is joined for the book by colorist Laura Martin and letterer John Workman. Edited by Scott Dunbier, Ragnarök’s published through IDW, and Chris Mowry’s credited with “production” on the first seven issues while Neil Uyetake gets the production credit on the eighth. What is Ragnarök beyond that? A fast-paced, adventurous saga. A grim playing-about with Norse myth. A super-hero high fantasy that nods to the past while telling a new and distinctive tale. And: a comic as exuberant as it is well-crafted. I sat down to read Annie Jacobsen’s 2015 book The Pentagon’s Brain — subtitled An Uncensored History of DARPA, America’s Top Secret Military Research Agency — thinking I’d get a new perspective on the development of the American military-industrial complex. And a new angle on the history of science in the 1950s and 1960s and beyond. Also that I’d learn a bit about the development of the internet, and who the people were who came up with it, and why they did, and what they were thinking. I got all of that. But I also found a new angle on science fiction, and the way SF shapes the world for better or for worse.

I sat down to read Annie Jacobsen’s 2015 book The Pentagon’s Brain — subtitled An Uncensored History of DARPA, America’s Top Secret Military Research Agency — thinking I’d get a new perspective on the development of the American military-industrial complex. And a new angle on the history of science in the 1950s and 1960s and beyond. Also that I’d learn a bit about the development of the internet, and who the people were who came up with it, and why they did, and what they were thinking. I got all of that. But I also found a new angle on science fiction, and the way SF shapes the world for better or for worse. I can understand scepticism of consciously political art. But I feel it’s often misplaced. If an artist is choosing to create art about politics, it probably means that those politics have a deep power for them. Which in turn is probably because the politics are connected to their emotions, worldview, beliefs — all the things that give art power. A political theme doesn’t elevate a work of art, but good art can illuminate the political. An artist may create consciously political art because politics are their passion. A storyteller may find their politics are the lens through which to present human truth and artistic power.

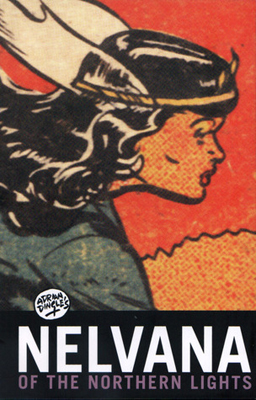

I can understand scepticism of consciously political art. But I feel it’s often misplaced. If an artist is choosing to create art about politics, it probably means that those politics have a deep power for them. Which in turn is probably because the politics are connected to their emotions, worldview, beliefs — all the things that give art power. A political theme doesn’t elevate a work of art, but good art can illuminate the political. An artist may create consciously political art because politics are their passion. A storyteller may find their politics are the lens through which to present human truth and artistic power.  In 2014, following a successful Kickstarter campaign, Hope Nicholson and Rachel Richey published Nelvana of the Northern Lights, a trade paperback reprinting all the appearances of the eponymous Canadian super-heroine from the 1940s. IDW gave the book a wider release in hardcover and paperback later that year. It contains over 300 pages of comics written and drawn by Nelvana’s creator Adrian Dingle, mostly in black and white, along with forewords by the editors, an introduction by Dr. Benjamin Woo (Assistant Professor of Communication Studies at Carleton University), and an afterword by Michael Hirsh (an artist and animator who founded a well-known animation studio named for Nelvana). It’s a nice package, designed by Ramón Pérez, a past winner of the Eisner, Harvey, and Shuster Awards.

In 2014, following a successful Kickstarter campaign, Hope Nicholson and Rachel Richey published Nelvana of the Northern Lights, a trade paperback reprinting all the appearances of the eponymous Canadian super-heroine from the 1940s. IDW gave the book a wider release in hardcover and paperback later that year. It contains over 300 pages of comics written and drawn by Nelvana’s creator Adrian Dingle, mostly in black and white, along with forewords by the editors, an introduction by Dr. Benjamin Woo (Assistant Professor of Communication Studies at Carleton University), and an afterword by Michael Hirsh (an artist and animator who founded a well-known animation studio named for Nelvana). It’s a nice package, designed by Ramón Pérez, a past winner of the Eisner, Harvey, and Shuster Awards. (I’ve decided to again delay my ongoing series of essays about C.S. Lewis, for a number of reasons. As it happens, though, there’s another piece I’ve been meaning to write for a while. So here it is.)

(I’ve decided to again delay my ongoing series of essays about C.S. Lewis, for a number of reasons. As it happens, though, there’s another piece I’ve been meaning to write for a while. So here it is.) I’d hoped to put up the fourth of my series of posts on the fiction of C.S. Lewis last week; I didn’t, and this isn’t that post either. I ended up spending more time running around over the holidays than I’d expected, so while I’m hoping to get the Lewis post up next Sunday, for the moment I want to do something different. Having seen a number of discussions about Hugo voting emerge over the previous days, I’d like to put forward some suggestions for the Dramatic Presentation categories.

I’d hoped to put up the fourth of my series of posts on the fiction of C.S. Lewis last week; I didn’t, and this isn’t that post either. I ended up spending more time running around over the holidays than I’d expected, so while I’m hoping to get the Lewis post up next Sunday, for the moment I want to do something different. Having seen a number of discussions about Hugo voting emerge over the previous days, I’d like to put forward some suggestions for the Dramatic Presentation categories. This is the third in a series of posts about the fictions of C.S. Lewis.

This is the third in a series of posts about the fictions of C.S. Lewis.  Yesterday I began a series of posts looking at the fiction of C.S. Lewis. Lewis has an unusually varied body of work, and I intend to wander through it chronologically and see what leaps out at me.

Yesterday I began a series of posts looking at the fiction of C.S. Lewis. Lewis has an unusually varied body of work, and I intend to wander through it chronologically and see what leaps out at me.  C.S. Lewis loved walking, and in one letter to his friend Arthur Greaves he wrote of a fifty-mile three-day expedition he undertook alongside other friends: walking by day through woods and river valleys, at evenings stopping at local houses where the company might discuss the nature of the Good. Bearing this image in mind I’ve decided to begin wandering through the terrain of Lewis’ fiction. It is well-trodden ground, as many others have done this before me. But there’s a certain charm in seeing things for oneself. It is also just possible that another pair of eyes may spot something new in even the most familiar landscape, if the terrain is varied enough. And Lewis’ writing, as a whole, stands out as heterogeneous indeed.

C.S. Lewis loved walking, and in one letter to his friend Arthur Greaves he wrote of a fifty-mile three-day expedition he undertook alongside other friends: walking by day through woods and river valleys, at evenings stopping at local houses where the company might discuss the nature of the Good. Bearing this image in mind I’ve decided to begin wandering through the terrain of Lewis’ fiction. It is well-trodden ground, as many others have done this before me. But there’s a certain charm in seeing things for oneself. It is also just possible that another pair of eyes may spot something new in even the most familiar landscape, if the terrain is varied enough. And Lewis’ writing, as a whole, stands out as heterogeneous indeed.