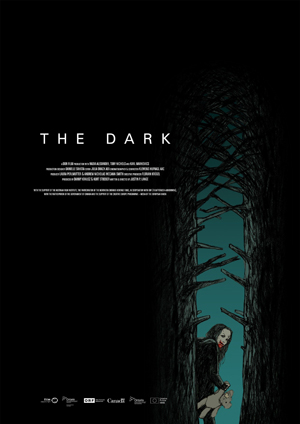

Fantasia 2018, Day 12, Part 1: The Dark

I had four movies on my schedule for Monday, July 23. Three of them were the work of one director. But before I got to those, I had an intriguing horror film at the J.A. De Sève Theatre to watch first: The Dark.

I had four movies on my schedule for Monday, July 23. Three of them were the work of one director. But before I got to those, I had an intriguing horror film at the J.A. De Sève Theatre to watch first: The Dark.

That screening was preceded by a short written and directed by Benjamin Swicker, “A/S/L.” I didn’t know what the title meant (an internet abbreviation for ‘age/sex/location’) and briefly thought I was about to see a film about American sign language; I was not. A middle-aged man chats up a young teenager on the internet, gets her to invite him over, and then finds out that all is not what he had thought it was. It’s competent enough, and brief, but I don’t think it gives too much away to say this is basically a vehicle for some admittedly spectacular gore effects. As such, it does the job.

The Dark was written and directed by Justin P. Lange. It’s the story of Mina (Nadia Alexander), a damaged and possibly undead girl who subsists in the woods, known by others only as a monster who kills any who enter her territory. Then one day fate brings to her an abused, blinded boy, Alex (Toby Nichols), who she doesn’t kill at once. In fact the two wounded children develop a strange bond. There’s a search afoot for Alex, though, and both police and volunteer seekers are coming into her woods. The two children go deeper into the wild, looking for some refuge together.

This is an atmospheric but highly graphic film that lets the images carry the story for long stretches. It doesn’t avoid having the characters speak to each other, but seems to invest each line with meaning. For example, it seems weirdly resonant that the first line of the movie is “You have to pay for that.” There are a lot of dark deeds done in this movie and a lot of those things come back to haunt the doer — and sometimes the sufferer. This is a movie about the cycle of abuse and characters trying, however instinctively, to move past it. But the world doesn’t make it easy, and the choices the characters make aren’t always ideal. You can literally see the damage the characters have suffered on their faces in the form of disturbing make-up effects. Whether that damage will destroy them is essentially the theme of the film.

I like to make out a rough schedule for Fantasia well ahead of time. But things always change. You hear things about movies as the festival goes on. What seems important a few days out seems less important in the moment. And then some choices are just hard to make. On Sunday July 22 I had one of those tough choices, which I’ll walk through here for the sake of recreating a bit of the subjective experience of Fantasia.

I like to make out a rough schedule for Fantasia well ahead of time. But things always change. You hear things about movies as the festival goes on. What seems important a few days out seems less important in the moment. And then some choices are just hard to make. On Sunday July 22 I had one of those tough choices, which I’ll walk through here for the sake of recreating a bit of the subjective experience of Fantasia. I knew Sunday, July 22, was going to be a long day for me at Fantasia. That was a good thing: it meant I’d be watching a lot of movies. At a certain point, I knew I’d have to make a choice about which ones I’d be seeing. But at least the first two were set in my mind, both playing at the Hall Theatre. The first was Fireworks, an anime tween love story with a time-twisting aspect. The second was Lôi Báo, a Vietnamese super-hero movie.

I knew Sunday, July 22, was going to be a long day for me at Fantasia. That was a good thing: it meant I’d be watching a lot of movies. At a certain point, I knew I’d have to make a choice about which ones I’d be seeing. But at least the first two were set in my mind, both playing at the Hall Theatre. The first was Fireworks, an anime tween love story with a time-twisting aspect. The second was Lôi Báo, a Vietnamese super-hero movie.  The third and last screening I saw on Saturday, July 21, was a selection of short films: the 2018 Born of Woman Showcase, presenting short genre works by women filmmakers. This year saw nine movies from eight countries.

The third and last screening I saw on Saturday, July 21, was a selection of short films: the 2018 Born of Woman Showcase, presenting short genre works by women filmmakers. This year saw nine movies from eight countries. I had three screenings I planned to attend at Fantasia on Saturday, July 21. The last would be a showcase of short films, but the first two were features. The day would begin at the Hall Theatre with The Travelling Cat Chronicles, an adaptation of a Japanese novel about a cat and assorted humans. Then would come Da Hu Fa, a 3D animated film from China about a diminutive martial-arts master seeking a lost prince within a hidden valley.

I had three screenings I planned to attend at Fantasia on Saturday, July 21. The last would be a showcase of short films, but the first two were features. The day would begin at the Hall Theatre with The Travelling Cat Chronicles, an adaptation of a Japanese novel about a cat and assorted humans. Then would come Da Hu Fa, a 3D animated film from China about a diminutive martial-arts master seeking a lost prince within a hidden valley.

Strangeness has many vectors; you can be weird in multiple directions at once. Whichever shape a movie takes, it’s often a good idea to have something strange in it. Something unexpected. You can usually count on movies at Fantasia to have at least one well-developed kind of weirdness in them, but the last two movies I saw on July 19, both at the large Hall Theatre, went in very different directions; one the strangest film (in a certain way) that I’d see this year, and the other imagining a world in which there is nothing unpredictable at all. The first was an odd Hollywood-set detective story, Under the Silver Lake. The second was Laplace’s Witch, an adaptation of a Japanese science-fiction novel, directed by Takashi Miike.

Strangeness has many vectors; you can be weird in multiple directions at once. Whichever shape a movie takes, it’s often a good idea to have something strange in it. Something unexpected. You can usually count on movies at Fantasia to have at least one well-developed kind of weirdness in them, but the last two movies I saw on July 19, both at the large Hall Theatre, went in very different directions; one the strangest film (in a certain way) that I’d see this year, and the other imagining a world in which there is nothing unpredictable at all. The first was an odd Hollywood-set detective story, Under the Silver Lake. The second was Laplace’s Witch, an adaptation of a Japanese science-fiction novel, directed by Takashi Miike. The first movie I saw at Fantasia on Thursday, July 19, was at the J.A. De Sève Theatre, a Korean film called The Fortress (Namhansanseong, 남한산성). Based on a novel by Hoon Kim, Dong-hyuk Hwang wrote the screenplay and directed his own adaptation. It’s a historical war story, set in 1636 when the Chinese Qing dynasty invaded Joseon-ruled Korea. The royal court has to flee before the Qing armies, taking refuge in a mountain castle, the fortress of the title. The Qing besiege the place, and the film follows what happens in the fortress as a result. More precisely, it follows the dispute between two of the officials of King Injo (Hae-il Park): on the one hand Myeong-gil Choi (Byung-hun Lee, who was in RED 2 and was Storm Shadow in the G.I. Joe movies), the Interior Minister who wants to negotiate with the Qing and if necessary surrender; and on the other, Sang-heon Kim (Yoon-seok Kim), the Minister of Rites who wants to hold out until the end, believing that an army’s gathering in the south that will strike north and relieve the fortress.

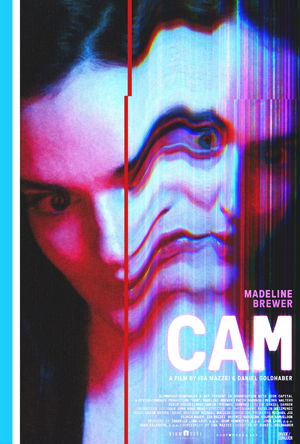

The first movie I saw at Fantasia on Thursday, July 19, was at the J.A. De Sève Theatre, a Korean film called The Fortress (Namhansanseong, 남한산성). Based on a novel by Hoon Kim, Dong-hyuk Hwang wrote the screenplay and directed his own adaptation. It’s a historical war story, set in 1636 when the Chinese Qing dynasty invaded Joseon-ruled Korea. The royal court has to flee before the Qing armies, taking refuge in a mountain castle, the fortress of the title. The Qing besiege the place, and the film follows what happens in the fortress as a result. More precisely, it follows the dispute between two of the officials of King Injo (Hae-il Park): on the one hand Myeong-gil Choi (Byung-hun Lee, who was in RED 2 and was Storm Shadow in the G.I. Joe movies), the Interior Minister who wants to negotiate with the Qing and if necessary surrender; and on the other, Sang-heon Kim (Yoon-seok Kim), the Minister of Rites who wants to hold out until the end, believing that an army’s gathering in the south that will strike north and relieve the fortress.  The only film I planned to see on Wednesday, July 18 was called Cam. Directed by Daniel Goldhaber from a script written by Isa Mazzei, it tells the story of a woman named Alice (Madeline Brewer, of The Handmaid’s Tale and Orange is the New Black) who works as an erotic webcam performer under the name of Lola — until she finds her account stolen by parties unknown. As Alice investigates she finds it’s more than just her financial information or identity that’s been stolen; someone who looks and sounds exactly like her is performing as Lola in her place, and this Lola is breaking all the rules Alice established for herself as a performer. Alice investigates and tries to regain control of her life, driving the story toward a brutal conclusion.

The only film I planned to see on Wednesday, July 18 was called Cam. Directed by Daniel Goldhaber from a script written by Isa Mazzei, it tells the story of a woman named Alice (Madeline Brewer, of The Handmaid’s Tale and Orange is the New Black) who works as an erotic webcam performer under the name of Lola — until she finds her account stolen by parties unknown. As Alice investigates she finds it’s more than just her financial information or identity that’s been stolen; someone who looks and sounds exactly like her is performing as Lola in her place, and this Lola is breaking all the rules Alice established for herself as a performer. Alice investigates and tries to regain control of her life, driving the story toward a brutal conclusion. I had one film on my schedule for Tuesday, July 17. It was a Japanese movie called Room Laundering, which looked like an odd fusion of comedy and horror. I wasn’t too sure what to make of it from the program description, but sometimes it’s the films that don’t lend themselves to easy description that’re the most rewarding. And so here.

I had one film on my schedule for Tuesday, July 17. It was a Japanese movie called Room Laundering, which looked like an odd fusion of comedy and horror. I wasn’t too sure what to make of it from the program description, but sometimes it’s the films that don’t lend themselves to easy description that’re the most rewarding. And so here.