Fantasia 2019, Day 10, Part 3: The Incredible Shrinking Wknd

The evening of July 20 saw me stay at the De Sève Theatre after the Born of Woman showcase for a feature film written and directed by Jon Mikel Caballero: The Incredible Shrinking Wknd. It’s a time-loop story, a subgenre that strikes me as having increased in popularity significantly over the past few years. We’re at the point, then, that a time-loop story has to do something different to stand out. So what does Wknd do?

The evening of July 20 saw me stay at the De Sève Theatre after the Born of Woman showcase for a feature film written and directed by Jon Mikel Caballero: The Incredible Shrinking Wknd. It’s a time-loop story, a subgenre that strikes me as having increased in popularity significantly over the past few years. We’re at the point, then, that a time-loop story has to do something different to stand out. So what does Wknd do?

It’s the story of Alba (Iria del Rio), newly turned 30, who’s spending a weekend partying at a cottage in the country with a group of acquaintances as well as her boyfriend of three years or so, Pablo (Adam Quintero). Alba’s generally thoughtless and lives for the day; despite having spent time at the cottage when she was young, she forgets to bring bottled water to a house with no indoor plumbing. Pablo wants something more, and in an argument one night breaks up with Alba. And then, not long after, reality resets and Alba gets to live through the weekend again. And again, and again; and then she notices the weekend’s getting shorter, and the time she has to live through is dwindling.

I’ll note to start with that the movie’s technically well-done. It looks very fine, with colours that establish moods, and a good variety of visually-interesting natural settings. Iria del Rio gives Alba a charismatic energy while making it clear that charisma’s covering up a certain kind of emptiness; there’s less to Alba than there appears, in a nicely-calculated way.

Narratively, the movie’s clever, almost a necessity in a time-loop story. The dialogue’s solid, and there’s a very nice visual idea (best left for the viewer to discover) that brings out the way the weekend’s shrinking. That twist itself is handled well, giving an increasing sense of tension as well as contrasting nicely with Alba’s tendency to care only about the present.

It gets a little odd in that Alba herself doesn’t reset, which becomes a minor plot point. If she gets drunk in one go-round, say, she’s hungover in the next. This is perhaps a way to talk about consequences, but it raises questions about the mechanism by which the time-loop exists in the first place and whether matter’s actually being transported through time. This is a film largely uninterested in such questions, though, and indeed the lack of concern with why the loop exists and why it works as it does is one of The Incredible Shrinking Wknd’s more frustrating aspects.

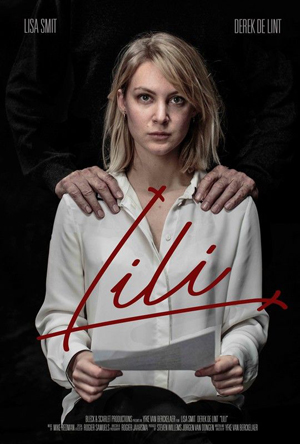

On the afternoon of Saturday, July 20, I passed by the De Sève Theatre for the Born of Woman 2019 series of short genre films directed by women. It was the fourth iteration of the showcase, and in four years it’s become a hot ticket; I nearly didn’t get in. But there was just space enough in the end, and so I was able to see the collection of 9 films representing half-a-dozen countries.

On the afternoon of Saturday, July 20, I passed by the De Sève Theatre for the Born of Woman 2019 series of short genre films directed by women. It was the fourth iteration of the showcase, and in four years it’s become a hot ticket; I nearly didn’t get in. But there was just space enough in the end, and so I was able to see the collection of 9 films representing half-a-dozen countries. On Saturday, July 20, I was down at the Hall Theatre bright and early — relatively speaking — for an 11 AM showing of Ride Your Wave (Kimi to, nami ni noretara, きみと、波にのれたら), an animated feature from director Masaaki Yuasa. I’d seen two of Yuasa’s previous works,

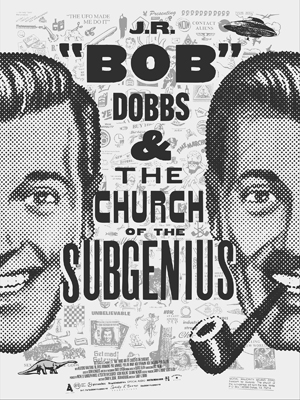

On Saturday, July 20, I was down at the Hall Theatre bright and early — relatively speaking — for an 11 AM showing of Ride Your Wave (Kimi to, nami ni noretara, きみと、波にのれたら), an animated feature from director Masaaki Yuasa. I’d seen two of Yuasa’s previous works,  My second and last movie on July 19 was a documentary named for its subject: J.R. “Bob” Dobbs and the Church of the Subgenius (a film known in some quarters as Slacking Towards Bethlehem). Directed by Sandy K. Boone, it’s a history of a mock religion which got started more than 40 years ago, and still goes strong today.

My second and last movie on July 19 was a documentary named for its subject: J.R. “Bob” Dobbs and the Church of the Subgenius (a film known in some quarters as Slacking Towards Bethlehem). Directed by Sandy K. Boone, it’s a history of a mock religion which got started more than 40 years ago, and still goes strong today.  On the evening of July 19 I sat down in the Hall Theatre for a screening of It Comes (Kuru, 来る), a Japanese horror film. Directed by Tetsuya Nakashima, it’s based on the novel Bogiwan ga kuru, by Ichi Sawamura, with a screenplay by Nakashima, Hideto Iwai, and Nobuhiro Monma. It’s clever and colourful, and at two and a half hours it’s also a sprawling film that justifies its length by twisting in ways you don’t expect. It’s also a success, an entertaining and occasionally chilling movie that builds a universe without being too detailed about the supernatural horror lurking beyond consensus reality.

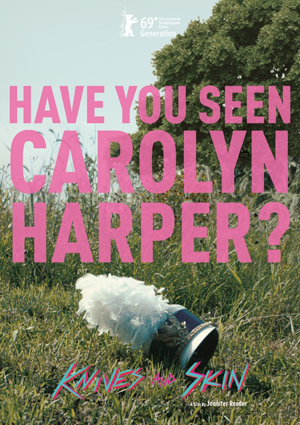

On the evening of July 19 I sat down in the Hall Theatre for a screening of It Comes (Kuru, 来る), a Japanese horror film. Directed by Tetsuya Nakashima, it’s based on the novel Bogiwan ga kuru, by Ichi Sawamura, with a screenplay by Nakashima, Hideto Iwai, and Nobuhiro Monma. It’s clever and colourful, and at two and a half hours it’s also a sprawling film that justifies its length by twisting in ways you don’t expect. It’s also a success, an entertaining and occasionally chilling movie that builds a universe without being too detailed about the supernatural horror lurking beyond consensus reality. My last film of July 18 was in the big Hall Theatre. Knives and Skin was written and directed by Jennifer Reeder, and begins as a girl dies a violent death in a small midwestern town. In the wake of her disappearance secrets begin to come to light, and tensions rise among both her classmates and the adults. The movie proceeds to explore the town and its inhabitants in a series of sometimes-linked vignettes.

My last film of July 18 was in the big Hall Theatre. Knives and Skin was written and directed by Jennifer Reeder, and begins as a girl dies a violent death in a small midwestern town. In the wake of her disappearance secrets begin to come to light, and tensions rise among both her classmates and the adults. The movie proceeds to explore the town and its inhabitants in a series of sometimes-linked vignettes. Before my second film of July 18, a surreal science-fiction movie from the director of

Before my second film of July 18, a surreal science-fiction movie from the director of  July 17 for me was a day of rest and running errands; then for my first film at Fantasia on July 18 I went to the De Sève Theatre to watch Maggie (메기). Directed by Yi Ok-seop from a film she wrote with star Koo Kyo-hwan, it’s the story of Yeo Yoon-young (Lee Ju-young), and her boyfriend Sung-won (Koo). Yoon-young’s a nurse at Love of Maria Hospital in Seoul. One day, an X-ray surfaces showing a man and a woman having sex in the X-ray room. The next day almost nobody comes in to work; the X-ray room’s a popular site for assignations, and everyone thinks they’re one of the figures in the X-ray. Yoon-young’s the only one who dares show her face, along with Doctor Lee (Moon So-ri). They end up forming an unlikely partnership as Maggie helps Lee learn to trust other people. Meanwhile, Sung-won finds work filling in sinkholes opening up in Korea, following an earthquake predicted by a catfish named Maggie — who also turns out to play an important role within the film.

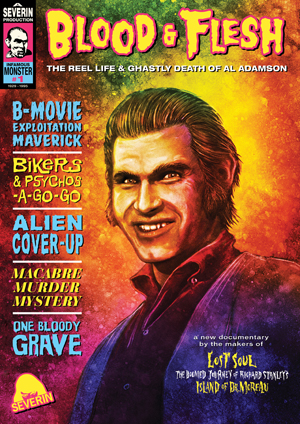

July 17 for me was a day of rest and running errands; then for my first film at Fantasia on July 18 I went to the De Sève Theatre to watch Maggie (메기). Directed by Yi Ok-seop from a film she wrote with star Koo Kyo-hwan, it’s the story of Yeo Yoon-young (Lee Ju-young), and her boyfriend Sung-won (Koo). Yoon-young’s a nurse at Love of Maria Hospital in Seoul. One day, an X-ray surfaces showing a man and a woman having sex in the X-ray room. The next day almost nobody comes in to work; the X-ray room’s a popular site for assignations, and everyone thinks they’re one of the figures in the X-ray. Yoon-young’s the only one who dares show her face, along with Doctor Lee (Moon So-ri). They end up forming an unlikely partnership as Maggie helps Lee learn to trust other people. Meanwhile, Sung-won finds work filling in sinkholes opening up in Korea, following an earthquake predicted by a catfish named Maggie — who also turns out to play an important role within the film. I expected my last film of July 16 would be a documentary called Blood & Flesh – The Reel Life and Ghastly Death of Al Adamson. You may not have heard of Adamson. I hadn’t. He was an exploitation filmmaker in the 1960s and 70s, responsible for titles like Satan’s Sadists, The Naughty Stewardesses, and Dracula Vs. Frankenstein, as well as not one but two separate films titled Psycho a Go-Go (Technically, one was Psycho à Go-Go; note accent). Introducing the documentary, Fantasia co-Director Mitch Davis described Adamson as more of a hustler than a filmmaker, then called up director David Gregory to briefly explain the film’s genesis. Gregory said it began as a special feature for a Blu-ray release, but the more he investigated Adamson, the more he realised the material was worth digging into more deeply. Thus, it’s now a feature, covering Adamson’s life, the films he made, and his awful death.

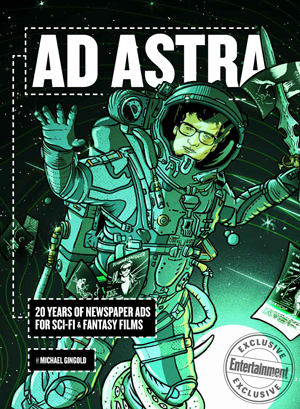

I expected my last film of July 16 would be a documentary called Blood & Flesh – The Reel Life and Ghastly Death of Al Adamson. You may not have heard of Adamson. I hadn’t. He was an exploitation filmmaker in the 1960s and 70s, responsible for titles like Satan’s Sadists, The Naughty Stewardesses, and Dracula Vs. Frankenstein, as well as not one but two separate films titled Psycho a Go-Go (Technically, one was Psycho à Go-Go; note accent). Introducing the documentary, Fantasia co-Director Mitch Davis described Adamson as more of a hustler than a filmmaker, then called up director David Gregory to briefly explain the film’s genesis. Gregory said it began as a special feature for a Blu-ray release, but the more he investigated Adamson, the more he realised the material was worth digging into more deeply. Thus, it’s now a feature, covering Adamson’s life, the films he made, and his awful death. On July 16 I started my day at Fantasia with a book launch. Michael Gingold’s book Ad Astra is coming out this fall, but attendees of his multimedia presentation had the chance to buy it earlier. It’s a follow-up to 2018’s Ad Nauseam: Newsprint Nightmares From the 1980s and its sequel to come in September, Ad Nauseam II: Newsprint Nightmares From the 1990s and 2000s. Those books were collections of classic newspaper ads for horror movies, while Ad Astra is subtitled 20 Years of Newspaper Ads for Sci-Fi & Fantasy Films.

On July 16 I started my day at Fantasia with a book launch. Michael Gingold’s book Ad Astra is coming out this fall, but attendees of his multimedia presentation had the chance to buy it earlier. It’s a follow-up to 2018’s Ad Nauseam: Newsprint Nightmares From the 1980s and its sequel to come in September, Ad Nauseam II: Newsprint Nightmares From the 1990s and 2000s. Those books were collections of classic newspaper ads for horror movies, while Ad Astra is subtitled 20 Years of Newspaper Ads for Sci-Fi & Fantasy Films.