Fantasia 2019, Day 15: Culture Shock

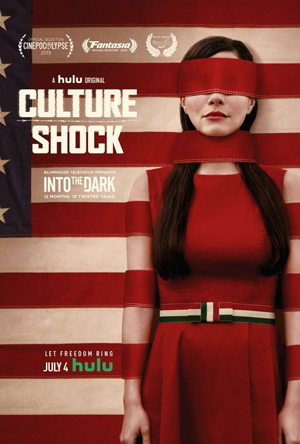

On June 25 I went to the De Sève Theatre for the one movie I’d see that day at the Concordia campus. It was called Culture Shock, and while it’s available on Hulu, this was a rare chance to see it in Canada.

On June 25 I went to the De Sève Theatre for the one movie I’d see that day at the Concordia campus. It was called Culture Shock, and while it’s available on Hulu, this was a rare chance to see it in Canada.

It was preceded by a short called “Re-Home,” directed by Izzy Lee. I’ll note for the record that I’m friends with the man who provided the music for the short, though I don’t think that affected my opinion one way or the other. In a future in which a wall along the southern border of the United States has been built, a poor Spanish-speaking woman (Gigi Saul Guerrero, director of Culture Shock) re-homes her baby, giving the child up for adoption to an Anglophone couple. But is something darker going on?

As usual at Fantasia, to ask that question is to get the answer “yes.” The short’s done well, with lots of atmosphere and style, but the twist at the end is the farthest thing from surprising. This feels like a piece of a larger story; either a beginning setting up something more complicated, or the ending of a tragedy that would have allowed us to be more invested in the mother and made her more individual. It’s highly watchable as it is, and certainly doesn’t overstay its welcome at only 8 minutes, but might actually be better served at a longer running time with more plot development.

Then came Culture Shock, which was made as an episode of Hulu’s horror anthology series Into the Dark. Each episode of the show is based on an American holiday, and this one was inspired by the Fourth of July. As noted, Culture Shock was directed by Gigi Saul Guerrero, who also worked on the script by James Benson and Efrén Hernández. She introduced the movie by noting it was a Blumhouse production, and saying that as an immigrant she felt she had a responsibility to tackle this material. She said she hopes it has something to say, and also provides an escape for 90 minutes.

It follows Marisol (Martha Higareda, of Altered Carbon fame), a heavily pregnant Mexican woman desperate to cross into the United States and begin a new life in a country she sees as having more opportunities. A good part of the movie follows her difficulties finding her way northward, showing her challenges as a woman finding out who she can trust and who she can’t; it also establishes the stories of other would-be immigrants travelling with her. When they all reach the border, though, something strange happens. Marisol wakes up in an idyllic American small town out of the 1950s or early 60s, a place obviously unreal. What’s happened to her? And how can she get free of this weird red-white-and-blue image of domesticity?

There was only one film I planned to watch on July 24, and that was writer-director Johannes Nyholm’s Koko-di Koko-da. It promised to be a strange movie about characters trying to break out of a time loop, and I settled in at the De Sève Theatre wondering at the horror elements implied by the film’s description in the festival catalogue.

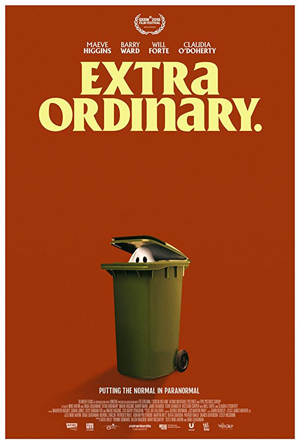

There was only one film I planned to watch on July 24, and that was writer-director Johannes Nyholm’s Koko-di Koko-da. It promised to be a strange movie about characters trying to break out of a time loop, and I settled in at the De Sève Theatre wondering at the horror elements implied by the film’s description in the festival catalogue. I had one film on my schedule for July 23, an Irish horror-themed comedy named Extra Ordinary. It was preceded by one of the best shorts I saw at Fantasia this year outside of a short film showcase.

I had one film on my schedule for July 23, an Irish horror-themed comedy named Extra Ordinary. It was preceded by one of the best shorts I saw at Fantasia this year outside of a short film showcase. I had been planning to head home after the first movie I saw on July 22,

I had been planning to head home after the first movie I saw on July 22,  On Monday, July 22, I was back at the Hall Theatre for one of the movies I was most anticipating. It was a new live-action manga adaptation from Hideki Takeuchi, director of the

On Monday, July 22, I was back at the Hall Theatre for one of the movies I was most anticipating. It was a new live-action manga adaptation from Hideki Takeuchi, director of the  My last screening of July 21 brought me back to the De Sève Theatre for a showcase of animated short genre films from China, Taiwan, Korea, and Japan, a grouping titled “Things That Go Bump In the East.” 11 films in a range of visual styles promised variety. I’d been having good luck with short films at the festival so far, and settled in eager to see what would come now.

My last screening of July 21 brought me back to the De Sève Theatre for a showcase of animated short genre films from China, Taiwan, Korea, and Japan, a grouping titled “Things That Go Bump In the East.” 11 films in a range of visual styles promised variety. I’d been having good luck with short films at the festival so far, and settled in eager to see what would come now. For my third movie of July 21 I wandered back to the Fantasia screening room. There, I settled in with a movie from the Philippines: Ode To Nothing. Written and directed by Dwein Ruedas Baltazar, it follows Sonya (Marietta Subong), a woman no longer young who owns her own funeral home in an unnamed town. Alone except for her father, Rudy (Joonee Gamboa), Sonya tries to keep the funeral home going despite debts to local loan shark Theodore (Dido Dela Paz). Then a body is brought to her for burial under suspicious circumstances. Rather than bury the corpse, though, Sonya begins to speak to it, and comes to think that the body of the old woman is bringing her luck — even to treat the body as her surrogate mother. Is the corpse responsible for the sudden influx of business to the funeral home? And even if it is, can you trust the gifts of the dead?

For my third movie of July 21 I wandered back to the Fantasia screening room. There, I settled in with a movie from the Philippines: Ode To Nothing. Written and directed by Dwein Ruedas Baltazar, it follows Sonya (Marietta Subong), a woman no longer young who owns her own funeral home in an unnamed town. Alone except for her father, Rudy (Joonee Gamboa), Sonya tries to keep the funeral home going despite debts to local loan shark Theodore (Dido Dela Paz). Then a body is brought to her for burial under suspicious circumstances. Rather than bury the corpse, though, Sonya begins to speak to it, and comes to think that the body of the old woman is bringing her luck — even to treat the body as her surrogate mother. Is the corpse responsible for the sudden influx of business to the funeral home? And even if it is, can you trust the gifts of the dead? For my second film of July 21 I stayed at the De Sève Theatre to watch one of my more anticipated movies of the festival. Each year Fantasia plays a Shaw Brothers film on 35mm — not one of the Shaw classics, usually, but one of their stranger works. The past few years I’ve seen

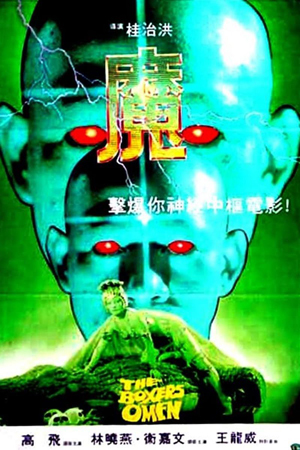

For my second film of July 21 I stayed at the De Sève Theatre to watch one of my more anticipated movies of the festival. Each year Fantasia plays a Shaw Brothers film on 35mm — not one of the Shaw classics, usually, but one of their stranger works. The past few years I’ve seen  My first film at Fantasia on July 21 was actually two films put together. In 2009 Atsuya Uki released a 25-minute short he’d written and directed, called “Cencoroll,” based on a one-shot manga he’d written and illustrated. The short was well-received, and over the last decade he’s created a 50-minute follow-up. The two movies have now been released as one, Cencoroll Connect (Senkorōru, センコロール コネクト). They work together as one story, but I wonder, never having seen the original “Cencoroll” on its own, whether the first short would have left more room for an audience’s imagination to work.

My first film at Fantasia on July 21 was actually two films put together. In 2009 Atsuya Uki released a 25-minute short he’d written and directed, called “Cencoroll,” based on a one-shot manga he’d written and illustrated. The short was well-received, and over the last decade he’s created a 50-minute follow-up. The two movies have now been released as one, Cencoroll Connect (Senkorōru, センコロール コネクト). They work together as one story, but I wonder, never having seen the original “Cencoroll” on its own, whether the first short would have left more room for an audience’s imagination to work. My last movie of July 20 was a horror film from South Africa. Written and directed by Harold Holscher, 8 has elements of the classical ghost story embedded in a larger tale of folklore and tragedy. It’s a period tale, set in 1977, and is set in a farm named Hemel op Aarde: Heaven on Earth.

My last movie of July 20 was a horror film from South Africa. Written and directed by Harold Holscher, 8 has elements of the classical ghost story embedded in a larger tale of folklore and tragedy. It’s a period tale, set in 1977, and is set in a farm named Hemel op Aarde: Heaven on Earth.