As Close as We’ll Get to a Completed Big Numbers: A Glimpse of a Lost Masterwork by Alan Moore and Bill Sienkiewicz

|

|

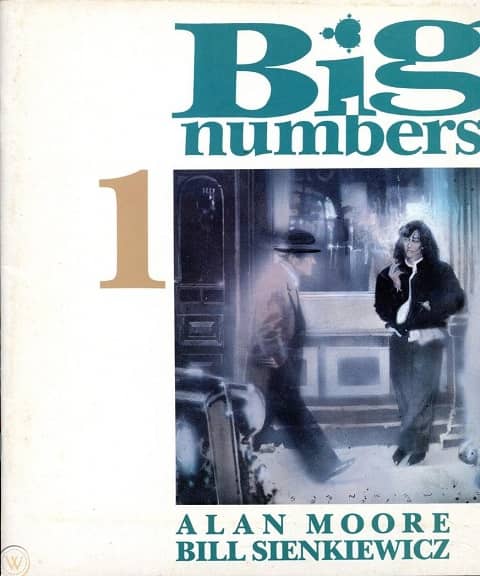

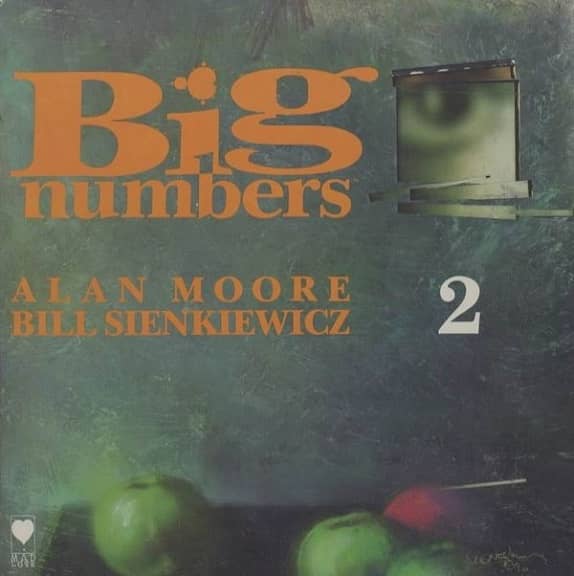

Big Numbers issues 1 and 2. Mad Love, April and August 1990. Covers by Bill Sienkiewicz

It’s one of the great might-have-beens of comics history. First announced in 1988, Big Numbers was going to be a 12-issue series written and conceived by Alan Moore with art by Bill Sienkiewicz about a major American shopping mall being built in a small English town. It would be an intricate social-realist story touching on colonialism, gender issues, and more — all tied together by the symbolism of fractal mathematics. Moore felt it would be the logical follow-up to Watchmen in terms of complexity and formal daring, following characters in the town as the mall changed their lives in various ways, and depicting their various interconnections, large and small.

Unfortunately, it never saw completion. Two issues came out in 1990 and a third was completed before Sienkiewicz, feeling overwhelmed by the project, stepped away. The series never resumed publication, and later plans for a TV adaptation came to nothing.

But back in 1988 Moore had created a massive grid-like outline, outlining the related stories of the various main characters. Comics artist James Harvey has now put up a strikingly well-designed web version of that chart, along with annotations from transcripts of an extensive conversation with Moore about the series as preparation for the TV show. Well-placed links help bring out the connections Moore had planned. It’s an excellent, easy-to-use resource for Moore fans — as well as a good read. And likely the most complete version of Big Numbers we’ll ever see.

Yesterday I posted my last full review of a film from the 2019 Fantasia International Film Festival. Today, then, a post looking back at this year’s Fantasia. First, as always, my profound thanks to everyone who puts the festival together. And thanks as well to the audiences, who give the festival a reason for being. Special thanks to everyone I watched movies with, everyone I waited in line with, and everyone who I talked with and hung out with during Fantasia 2019.

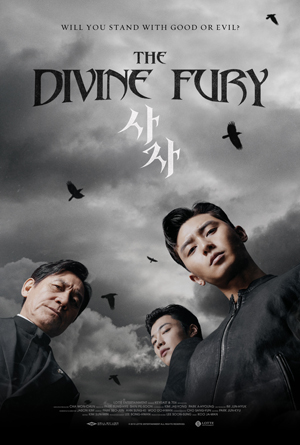

Yesterday I posted my last full review of a film from the 2019 Fantasia International Film Festival. Today, then, a post looking back at this year’s Fantasia. First, as always, my profound thanks to everyone who puts the festival together. And thanks as well to the audiences, who give the festival a reason for being. Special thanks to everyone I watched movies with, everyone I waited in line with, and everyone who I talked with and hung out with during Fantasia 2019. All good things must come to an end, they say, and for me Fantasia 2019 ended at the Hall Theatre with the Korean action-horror movie The Divine Fury (사자, romanised as Saja, literally Emissary). Directed by Kim Joo-hwan, it follows Yong-hu (Park Seo-jun), a champion MMA fighter who lost his father under mysterious circumstances at a young age. In the present, when mysterious wounds appear on his hands and he is attacked by a demonic force, a blind shaman guides him to exorcist Father Ahn (Ahn Sung-ki), who tells him the wounds are stigmata and give him great power in fighting demons. The two team up, reluctantly on the part of Yong-hu, who holds a grudge against Christianity after the death of his father. But there are dark forces at work in Seoul, and Yong-hu must use all his skills to defeat the forces of hell on earth.

All good things must come to an end, they say, and for me Fantasia 2019 ended at the Hall Theatre with the Korean action-horror movie The Divine Fury (사자, romanised as Saja, literally Emissary). Directed by Kim Joo-hwan, it follows Yong-hu (Park Seo-jun), a champion MMA fighter who lost his father under mysterious circumstances at a young age. In the present, when mysterious wounds appear on his hands and he is attacked by a demonic force, a blind shaman guides him to exorcist Father Ahn (Ahn Sung-ki), who tells him the wounds are stigmata and give him great power in fighting demons. The two team up, reluctantly on the part of Yong-hu, who holds a grudge against Christianity after the death of his father. But there are dark forces at work in Seoul, and Yong-hu must use all his skills to defeat the forces of hell on earth. The nice thing about my last day of Fantasia was that rather than sit in one place, I would watch something on my own in the screening room, then something at the small De Sève Cinema, and finally something at the big Hall Theatre. It had the well-rounded feeling of a good summing-up.

The nice thing about my last day of Fantasia was that rather than sit in one place, I would watch something on my own in the screening room, then something at the small De Sève Cinema, and finally something at the big Hall Theatre. It had the well-rounded feeling of a good summing-up. After taking a day to attend to various non-cinema matters, I came early to the last day of the Fantasia Film Festival. I had two movies I wanted to see in theatres, but first I wanted to catch up on something I’d missed when played on the big screen: the 2019 International Science Fiction Short Film Showcase. Luckily, I was able to watch it at the Fantasia screening room. Uncharacteristically, American shorts dominated this year; in an appropriately science-fictional statistic, 7 of 9 movies were from the US, with one from Australia that ended the showcase (at least in the order described in the Fantasia program) and one from Ukraine that began it.

After taking a day to attend to various non-cinema matters, I came early to the last day of the Fantasia Film Festival. I had two movies I wanted to see in theatres, but first I wanted to catch up on something I’d missed when played on the big screen: the 2019 International Science Fiction Short Film Showcase. Luckily, I was able to watch it at the Fantasia screening room. Uncharacteristically, American shorts dominated this year; in an appropriately science-fictional statistic, 7 of 9 movies were from the US, with one from Australia that ended the showcase (at least in the order described in the Fantasia program) and one from Ukraine that began it. I approached my second and last film of July 30 with real uncertainty. I’d never seen many tokusatsu films or TV shows, and what I had seen I hadn’t cared for. (‘Tokusatsu’ literally means something like ‘special effects,’ but in the West it’s come especially to refer to shows like Power Rangers or Kamen Rider.) Still, playing in the De Sève Cinema was Garo — Under the Moonbow (Garo: gekkô no tabibito, 牙狼 — 月虹ノ旅人, also translated Garo: Moonbow Traveler), written and directed by Keita Amemiya. It’s the latest installment of a franchise, created by Amemiya, which began with a 2005 TV series and has continued through more TV shows, live-action movies, and anime series. as well as video games, manga, and various other tie-ins. A veteran creator of tokusatsu dramas, Amemiya is particularly known for his powerful design sense, and the images and description of the film promised a stylish fantasy adventure. Although it’d be my first experience with a series that had dozens of hours of continuity behind it, I decided it was worth passing up a chance to see The Crow on the big screen in order to watch Under the Moonbow.

I approached my second and last film of July 30 with real uncertainty. I’d never seen many tokusatsu films or TV shows, and what I had seen I hadn’t cared for. (‘Tokusatsu’ literally means something like ‘special effects,’ but in the West it’s come especially to refer to shows like Power Rangers or Kamen Rider.) Still, playing in the De Sève Cinema was Garo — Under the Moonbow (Garo: gekkô no tabibito, 牙狼 — 月虹ノ旅人, also translated Garo: Moonbow Traveler), written and directed by Keita Amemiya. It’s the latest installment of a franchise, created by Amemiya, which began with a 2005 TV series and has continued through more TV shows, live-action movies, and anime series. as well as video games, manga, and various other tie-ins. A veteran creator of tokusatsu dramas, Amemiya is particularly known for his powerful design sense, and the images and description of the film promised a stylish fantasy adventure. Although it’d be my first experience with a series that had dozens of hours of continuity behind it, I decided it was worth passing up a chance to see The Crow on the big screen in order to watch Under the Moonbow. My first movie on July 30 was the first feature by two French directors of independent short films, Caroline Poggi and Jonathan Vinel. Jessica Forever, which the duo wrote as well as directed, is set in a near future in which disaffected and violent youth, mostly male, roam empty suburbs. The law hunts them down with killer drones, and the movie opens with a cloud of drones after one man, Kevin (Eddy Suiveng), who has squatted in an empty house. He’s saved from the law by a mysterious woman named Jessica (Aomi Muyock) and her squad of young men, who welcome Kevin into the fold.

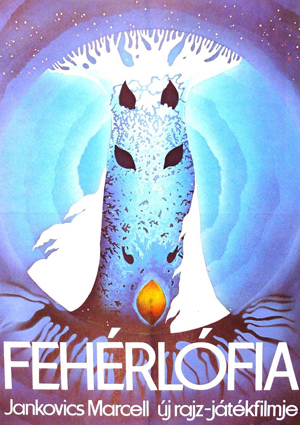

My first movie on July 30 was the first feature by two French directors of independent short films, Caroline Poggi and Jonathan Vinel. Jessica Forever, which the duo wrote as well as directed, is set in a near future in which disaffected and violent youth, mostly male, roam empty suburbs. The law hunts them down with killer drones, and the movie opens with a cloud of drones after one man, Kevin (Eddy Suiveng), who has squatted in an empty house. He’s saved from the law by a mysterious woman named Jessica (Aomi Muyock) and her squad of young men, who welcome Kevin into the fold. The last of the four movies I had on my schedule for July 29 promised to be interesting on any number of levels. Son of the White Mare (Fehérlófia) is an animated film made in 1981 by Hungarian Marcell Jankovics, directed by him from a script he wrote with László György. It’s based on the work of poet László Arany and folktales of the Magyars and Avars; Jankovics, who has published 15 books on comparative mythology, picked and chose from among the various versions of the tale to create what he wanted — a weird, protean, eye-popping, archetypal light show.

The last of the four movies I had on my schedule for July 29 promised to be interesting on any number of levels. Son of the White Mare (Fehérlófia) is an animated film made in 1981 by Hungarian Marcell Jankovics, directed by him from a script he wrote with László György. It’s based on the work of poet László Arany and folktales of the Magyars and Avars; Jankovics, who has published 15 books on comparative mythology, picked and chose from among the various versions of the tale to create what he wanted — a weird, protean, eye-popping, archetypal light show. My third screening on July 29 was a double-feature at the De Sève Cinema of two animated movies, a long short and a short feature. “A Japanese Boy Who Draws” (ある日本の絵描き少年) is 20 minutes long. Twilight, which I immediately came to think of as (Not That) Twilight (and in fact some places online translate the title 薄暮, Hakubo, as Project Twilight), is 53 minutes long. They’re both slice-of-life films about young people in Japan making art, but are otherwise very different narratively and visually. Which is to say they have enough in common and enough contrast to make a fine double bill.

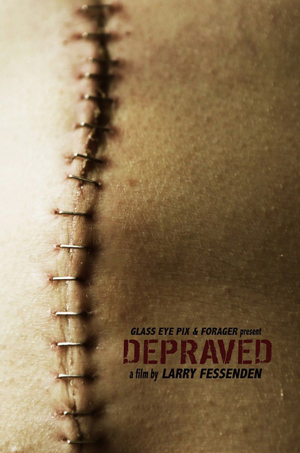

My third screening on July 29 was a double-feature at the De Sève Cinema of two animated movies, a long short and a short feature. “A Japanese Boy Who Draws” (ある日本の絵描き少年) is 20 minutes long. Twilight, which I immediately came to think of as (Not That) Twilight (and in fact some places online translate the title 薄暮, Hakubo, as Project Twilight), is 53 minutes long. They’re both slice-of-life films about young people in Japan making art, but are otherwise very different narratively and visually. Which is to say they have enough in common and enough contrast to make a fine double bill. One of the things that most fascinates me about film is the way Frankenstein is at least as important in that medium as it is in prose. Obviously this importance is most visible in genre film, but it’s there one way or another in the mainstream too — consider Gods and Monsters. From at least 1910, when the story was adapted into a then-epic ten-minute movie, through the tremendously important 1931 Boris Karloff version, it’s a story that’s haunted cinema. One way or another the tale or the monster comes up regularly at Fantasia, whether in Guillermo del Toro

One of the things that most fascinates me about film is the way Frankenstein is at least as important in that medium as it is in prose. Obviously this importance is most visible in genre film, but it’s there one way or another in the mainstream too — consider Gods and Monsters. From at least 1910, when the story was adapted into a then-epic ten-minute movie, through the tremendously important 1931 Boris Karloff version, it’s a story that’s haunted cinema. One way or another the tale or the monster comes up regularly at Fantasia, whether in Guillermo del Toro