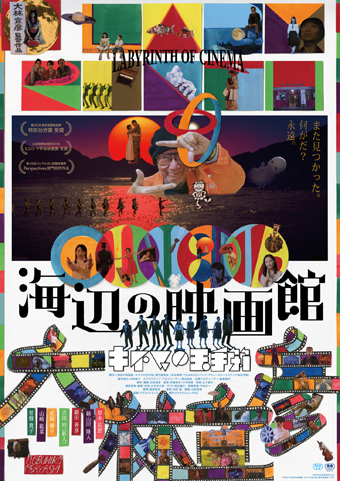

Fantasia 2020, Part IX: Labyrinth of Cinema

Nobuhiko Obayashi, the director best known for the surreal 1977 horror film House (Hausu, ハウス), died on April 10 this year. His final film is Labyrinth of Cinema (海辺の映画館 キネマの玉手箱), which he wrote as well as directed. Just as visually extravagant as House, it grapples with weightier themes — specifically, the nature of cinema and of war, and how film can be used to protest war. It’s therefore also a rumination on history, specifically the history of Japan in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, and how that history was depicted in the movies of its time. And Labyrinth gets at these things through the frame of a fantasy story about movie spectators unstuck in time and narrative. Obayashi swung for the fences with this film, a three-hour long experience that feels like a career summation, a director reflecting on his life and craft and art.

Nobuhiko Obayashi, the director best known for the surreal 1977 horror film House (Hausu, ハウス), died on April 10 this year. His final film is Labyrinth of Cinema (海辺の映画館 キネマの玉手箱), which he wrote as well as directed. Just as visually extravagant as House, it grapples with weightier themes — specifically, the nature of cinema and of war, and how film can be used to protest war. It’s therefore also a rumination on history, specifically the history of Japan in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, and how that history was depicted in the movies of its time. And Labyrinth gets at these things through the frame of a fantasy story about movie spectators unstuck in time and narrative. Obayashi swung for the fences with this film, a three-hour long experience that feels like a career summation, a director reflecting on his life and craft and art.

It begins in an almost essayistic manner, with the musings of a narrator named Fanta G (Yukihiro Takahashi), floating among memory fragments in a time machine that eventually brings him to the present day and the seaside city of Onomichi (Obayashi’s home). The last cinema in town will be closing at dawn, but before that happens an audience will take in one last picture show. And then some of members of that audience are caught up on the images onscreen — three young men chasing a mysterious teen named Noriko (Rei Yoshida).

The film ranges across the years roughly from 1868 to 1945, talking about Japan’s history, how it played out in film, and how Japanese film itself developed. The decline of samurai and the rise of mass mechanised warfare is seen through a peculiar lens, the garrulous Fanta explaining everything necessary as the film goes along. The characters from the audience take on different roles, playing out different stories across different genres and forms. If the frame concept of the Onomichi movie house is self-consciously surreal, the scenarios that incorporate the audience members grow more serious as the film goes on.

The movie begins with a blitz of images and ideas, introducing concepts at a furious pace to the point that ten minutes in I almost stopped taking notes. Not only do we get Fanta G’s time travelling, and then the cinema, and then an assortment of characters, but we’re told that the film will be referring to the writings of poet Chuya Nakahara (1907-1937), and soon get dance numbers and black-and-white scenes and title cards and even passages like silent film. And a visual approach seemingly based on collage, compositing together images like an odd kind of cartoon. Thankfully, it slows down, and in fact continues to slow as the film goes along. But not before a range of genres appears onscreen — musicals and yakuza films and samurai movies — somehow all coexisting.

Day 5 of Fantasia began for me by watching Simon Barrett give bad career advice. Barrett’s the writer of horror movies such as The Guest and You’re Next, and he took questions from an online audience for what turned out to be more than two hours in a self-effacing discussion about how the modern movie industry works (or fails to), and how aspiring filmmakers can prepare themselves for entering that world. It was a funny, detailed, and generous discussion, which

Day 5 of Fantasia began for me by watching Simon Barrett give bad career advice. Barrett’s the writer of horror movies such as The Guest and You’re Next, and he took questions from an online audience for what turned out to be more than two hours in a self-effacing discussion about how the modern movie industry works (or fails to), and how aspiring filmmakers can prepare themselves for entering that world. It was a funny, detailed, and generous discussion, which

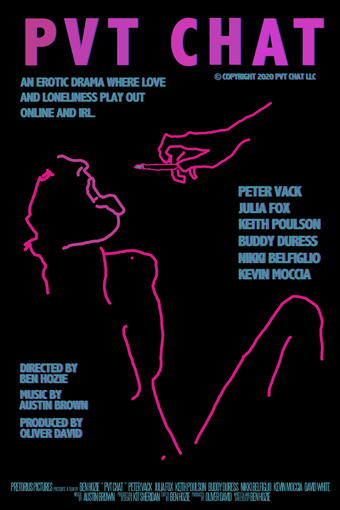

One of the new wrinkles to Fantasia this year is the existence of a Discord where filmmakers and critics and audiences can chat with each other about the movies playing the festival. It’s already proved quite useful to me, as seeing other people discussing films has helped draw my attention to a few titles I’d originally dismissed as uninteresting or out of step with this web site’s focus. A case in point was the movie I watched late on Fantasia’s second day, writer-director Ben Hozie’s PVT Chat.

One of the new wrinkles to Fantasia this year is the existence of a Discord where filmmakers and critics and audiences can chat with each other about the movies playing the festival. It’s already proved quite useful to me, as seeing other people discussing films has helped draw my attention to a few titles I’d originally dismissed as uninteresting or out of step with this web site’s focus. A case in point was the movie I watched late on Fantasia’s second day, writer-director Ben Hozie’s PVT Chat.  As part of the unusual nature of this year’s Fantasia, the festival organisers set up many more non-film special events than usual. Each day boasts a presentation, panel discussion, or other streamed activity, all of them to be archived on the festival’s YouTube page (in fact the organisers have just announced they’ll host

As part of the unusual nature of this year’s Fantasia, the festival organisers set up many more non-film special events than usual. Each day boasts a presentation, panel discussion, or other streamed activity, all of them to be archived on the festival’s YouTube page (in fact the organisers have just announced they’ll host  My first scheduled film at Fantasia 2020 was Special Actors (Supesharu Akutâzu, スペシャルアクターズ), written and directed by Shinichiro Ueda. I loved Ueda’s previous film, 2018’s One Cut of the Dead (Kamera wo tomeruna!, カメラを止めるな!), and this is his first solo feature since; he co-directed 2019’s Aesop’s Game (Isoppu no Omou Tsubo, イソップの思うツボ), and this year

My first scheduled film at Fantasia 2020 was Special Actors (Supesharu Akutâzu, スペシャルアクターズ), written and directed by Shinichiro Ueda. I loved Ueda’s previous film, 2018’s One Cut of the Dead (Kamera wo tomeruna!, カメラを止めるな!), and this is his first solo feature since; he co-directed 2019’s Aesop’s Game (Isoppu no Omou Tsubo, イソップの思うツボ), and this year  Most of the movies I want to see at Fantasia 2020 play at a scheduled time, but quite a few are available on demand for the next two weeks. One of those struck me as a good place to start this year’s unusual Fantasia-from-home: Justin McConnell’s documentary Clapboard Jungle. It’s about the process of putting a film together, focussing not so much on the technical details of directing but the much longer struggle to find financing.

Most of the movies I want to see at Fantasia 2020 play at a scheduled time, but quite a few are available on demand for the next two weeks. One of those struck me as a good place to start this year’s unusual Fantasia-from-home: Justin McConnell’s documentary Clapboard Jungle. It’s about the process of putting a film together, focussing not so much on the technical details of directing but the much longer struggle to find financing.  Usually by this point in the year I’ve begun posting reviews of films I saw earlier in the summer at Montreal’s Fantasia International Film Festival. Here as elsewhere, things are different in 2020. When the coronavirus pandemic hit, Fantasia was postponed to the end of August. It looked like this year’s Festival was in danger of not happening at all. But the wonderful and dedicated people behind Fantasia have made it work;

Usually by this point in the year I’ve begun posting reviews of films I saw earlier in the summer at Montreal’s Fantasia International Film Festival. Here as elsewhere, things are different in 2020. When the coronavirus pandemic hit, Fantasia was postponed to the end of August. It looked like this year’s Festival was in danger of not happening at all. But the wonderful and dedicated people behind Fantasia have made it work;  Ursula Pflug’s fiction demands to be savoured. Her new collection, Seeds And Other Stories, holds 26 short fictions ranging in length from flash fiction to short novelettes, each marked out by precise language and fantastic happenings seen edge-on. They’re not linked by plot but by threads of imagery: portals to other places; hallucinatory new drugs named for colours; gardening, and plants sprouting from the earth or human bodies. Each individual piece on its own carries a powerful emotional weight. Together it becomes difficult to read more than a few in a sitting, and that is no bad thing.

Ursula Pflug’s fiction demands to be savoured. Her new collection, Seeds And Other Stories, holds 26 short fictions ranging in length from flash fiction to short novelettes, each marked out by precise language and fantastic happenings seen edge-on. They’re not linked by plot but by threads of imagery: portals to other places; hallucinatory new drugs named for colours; gardening, and plants sprouting from the earth or human bodies. Each individual piece on its own carries a powerful emotional weight. Together it becomes difficult to read more than a few in a sitting, and that is no bad thing.