Fantasia 2020, Part XXIX: Unearth

There’s an old line that says science fiction literalises metaphors. It’s a line that applies to fantasy and horror, too. It means that, for example, a realist book may say that somebody walking through their old house is haunted by memories like the ghosts of their past, while a horror story might have that person be actually haunted by an actual ghost representing that past. What is metaphor in one case is literal in the other. But still a metaphor, as well, still symbolising something more than itself. Part of the trick of writing stories of the fantastic is knowing how to handle the metaphorical and the literal — knowing exactly how literal to make the literalised metaphor, and how to explore what literalising the metaphor brings the story, and how to explore the metaphor as metaphor while keeping it a literal thing.

There’s an old line that says science fiction literalises metaphors. It’s a line that applies to fantasy and horror, too. It means that, for example, a realist book may say that somebody walking through their old house is haunted by memories like the ghosts of their past, while a horror story might have that person be actually haunted by an actual ghost representing that past. What is metaphor in one case is literal in the other. But still a metaphor, as well, still symbolising something more than itself. Part of the trick of writing stories of the fantastic is knowing how to handle the metaphorical and the literal — knowing exactly how literal to make the literalised metaphor, and how to explore what literalising the metaphor brings the story, and how to explore the metaphor as metaphor while keeping it a literal thing.

All of which came to mind when I saw Unearth on the start of the eleventh day of the Fantasia Film Festival. The movie was directed by John C. Lyons and Dorota Swies from a script by Lyons and Kelsey Goldberg, and it’s concerned with industry coming into a small town and unloosing something terrible. But it’s a slow build to get to a point that most horror movies would put up front, and by the time the horror emerges you wonder if it was really needed.

The film follows two families struggling to make ends meet, one a farming family headed by matriarch Kathryn Dolan (Adrienne Barbeau), the other by garage owner George Lomack (Marc Blucas). The first act of the film introduces us to the Dolans and Lomacks and shows us their hopes and dreams being strangled by poverty, so that we understand why George is ready to lease his land to an oil company. The company moves in and starts a fracking operation, causing the environment to degrade rapidly. And then something worse is disturbed.

But that something worse does not become obvious until over an hour into a 94-minute movie. When it does, it pays off some hints and imagery from earlier in the film. But those hints have been so subtle it takes a while even after the horror really emerges to understand what it is we’re seeing.

For much of the movie, in fact, it looks like the oil company and perhaps capitalism in general are the monsters. The oil company emissary offers a sinister deal to various characters, preying upon the weakest and least able to resist. After the evil deal’s made, the surroundings become a hell. This is barely a metaphor; the need for money and the corruption of the land make the oil company, distant and untouchable, a demonic force.

I’ve mentioned that many of the films I saw at this year’s Fantasia were haunted-house stories. Or: horror movies that revolve around a specific architectural location. That’s an intriguing coincidence in the year of COVID-19, but perhaps speaks to filmmakers finding a way to limit budgets and get the most use possible out of their locations. Which brings me to 2011, a film set in a single apartment and a kind of ghost story that begins and ends with the horror-thriller form. But this only becomes clear at the very end, for mainly this is an experimental and ambitious film that wanders through different genres and types of stories.

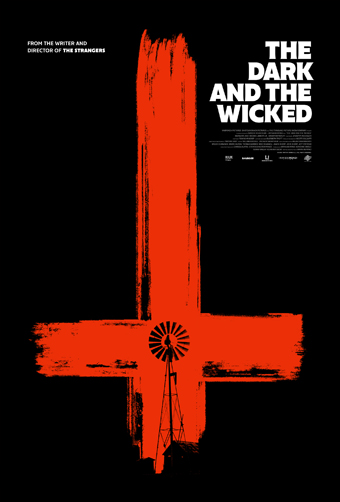

I’ve mentioned that many of the films I saw at this year’s Fantasia were haunted-house stories. Or: horror movies that revolve around a specific architectural location. That’s an intriguing coincidence in the year of COVID-19, but perhaps speaks to filmmakers finding a way to limit budgets and get the most use possible out of their locations. Which brings me to 2011, a film set in a single apartment and a kind of ghost story that begins and ends with the horror-thriller form. But this only becomes clear at the very end, for mainly this is an experimental and ambitious film that wanders through different genres and types of stories.  Religion’s a recurring subject for horror, and for a lot of reasons; there’s a lot in there to be scared about. More, from at least the 18th century onward writers have followed Edmund Burke and Ann Radcliffe in linking horror with the sublime. When horror fiction in the West has grappled with religion, naturally enough it’s tended to use Christian symbols, ideas, and sometimes even theology — whether in something as simple as the crucifix turning away a vampire, or in something more central to the story, as showing the birth of Satan’s child in The Omen or Rosemary’s Baby.

Religion’s a recurring subject for horror, and for a lot of reasons; there’s a lot in there to be scared about. More, from at least the 18th century onward writers have followed Edmund Burke and Ann Radcliffe in linking horror with the sublime. When horror fiction in the West has grappled with religion, naturally enough it’s tended to use Christian symbols, ideas, and sometimes even theology — whether in something as simple as the crucifix turning away a vampire, or in something more central to the story, as showing the birth of Satan’s child in The Omen or Rosemary’s Baby.  The Japanese image of the three wise monkeys is as early as the 16th century: one monkey with hands over eyes, the next with hands over ears, the third with hands over mouth. See no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil; thus the monkeys’ names, Mizaru, Kikazaru, and Iwazaru, ‘not-seeing,’ ‘not-hearing,’ and ‘not-speaking.’ There’s a pun in Japanase on zaru, not, and saru, monkey, so collectively the trio’s simply ‘three monkeys,’ or sanzaru.

The Japanese image of the three wise monkeys is as early as the 16th century: one monkey with hands over eyes, the next with hands over ears, the third with hands over mouth. See no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil; thus the monkeys’ names, Mizaru, Kikazaru, and Iwazaru, ‘not-seeing,’ ‘not-hearing,’ and ‘not-speaking.’ There’s a pun in Japanase on zaru, not, and saru, monkey, so collectively the trio’s simply ‘three monkeys,’ or sanzaru. By Day 10 of Fantasia I’d started to skip the panels and special presentations. They all looked interesting to greater or lesser degrees, but while the movies were only available while the festival was still going on, the panels would stay up afterward. Still, Day 10 was an exception, with my schedule free for a panel I was particularly interested in: “New York State Of Horror,” hosted by author Michael Gingold. It took a look at how and when New York City became a setting for horror films — something unusual in the early decades of filmmaking, when horror was typically set in ancient European locales. King Kong (1933) was an obvious exception, but Gingold observed that Rosemary’s Baby was the real trail-blazer for New York horror stories in film, followed in the 70s and 80s by more tales of urban terror. It was a good discussion, with contributions from directors Bill Lustig and Larry Fessenden (

By Day 10 of Fantasia I’d started to skip the panels and special presentations. They all looked interesting to greater or lesser degrees, but while the movies were only available while the festival was still going on, the panels would stay up afterward. Still, Day 10 was an exception, with my schedule free for a panel I was particularly interested in: “New York State Of Horror,” hosted by author Michael Gingold. It took a look at how and when New York City became a setting for horror films — something unusual in the early decades of filmmaking, when horror was typically set in ancient European locales. King Kong (1933) was an obvious exception, but Gingold observed that Rosemary’s Baby was the real trail-blazer for New York horror stories in film, followed in the 70s and 80s by more tales of urban terror. It was a good discussion, with contributions from directors Bill Lustig and Larry Fessenden ( ‘Weird’ is less of a concrete descriptor than might at first appear. There are multiple subcategories of weird, and different things called weird can produce very different experiences. This is especially so when a work of weirdness mixes different weird things.

‘Weird’ is less of a concrete descriptor than might at first appear. There are multiple subcategories of weird, and different things called weird can produce very different experiences. This is especially so when a work of weirdness mixes different weird things. One of the fascinating things about art is the way it speaks to its exact moment. That’s even more fascinating with film, which has such a long gestation time; write a movie, shoot the movie, then edit the movie and work on it in postproduction, and it’ll come out years after it was conceived. Which is why it was fascinating to see so many films at this year’s Fantasia that revolved around haunted houses. Occasionally the haunted building might be something like a school (as in

One of the fascinating things about art is the way it speaks to its exact moment. That’s even more fascinating with film, which has such a long gestation time; write a movie, shoot the movie, then edit the movie and work on it in postproduction, and it’ll come out years after it was conceived. Which is why it was fascinating to see so many films at this year’s Fantasia that revolved around haunted houses. Occasionally the haunted building might be something like a school (as in  Day 9 of Fantasia began for me with The Block Island Sound. Directed by brothers Kevin and Matthew McManus, and written by Matthew, it’s a horror movie named for a body of water off the coast of Rhode Island. It’s the rare horror story that deals with inhuman mysteries on the northeastern coast of the United States while not feeling Lovecraftian at all.

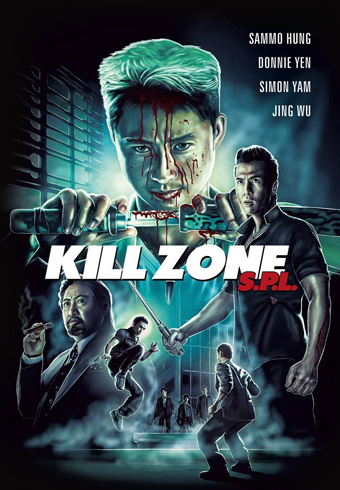

Day 9 of Fantasia began for me with The Block Island Sound. Directed by brothers Kevin and Matthew McManus, and written by Matthew, it’s a horror movie named for a body of water off the coast of Rhode Island. It’s the rare horror story that deals with inhuman mysteries on the northeastern coast of the United States while not feeling Lovecraftian at all. One of the lovely things about covering Fantasia is the chance to see genre classics I missed the first time around, often brought back to the screen in a restored version. Again in 2020, notwithstanding its streaming-only nature, Fantasia revived a number of great films from prior years. While my own inefficiency with scheduling meant I ended up missing Johnnie To’s A Hero Never Dies, I saw many of the others, including Wilson Yip’s 2005 movie SPL: Kill Zone (also just Kill Zone, originally SPL: Sha Po Lang, 殺破狼).

One of the lovely things about covering Fantasia is the chance to see genre classics I missed the first time around, often brought back to the screen in a restored version. Again in 2020, notwithstanding its streaming-only nature, Fantasia revived a number of great films from prior years. While my own inefficiency with scheduling meant I ended up missing Johnnie To’s A Hero Never Dies, I saw many of the others, including Wilson Yip’s 2005 movie SPL: Kill Zone (also just Kill Zone, originally SPL: Sha Po Lang, 殺破狼). There is, or was, or might have been according to some, a movement in Greek cinema that started and flourished in the first half of the second decade of the twenty-first century called the Greek Weird Wave. This movement,

There is, or was, or might have been according to some, a movement in Greek cinema that started and flourished in the first half of the second decade of the twenty-first century called the Greek Weird Wave. This movement,