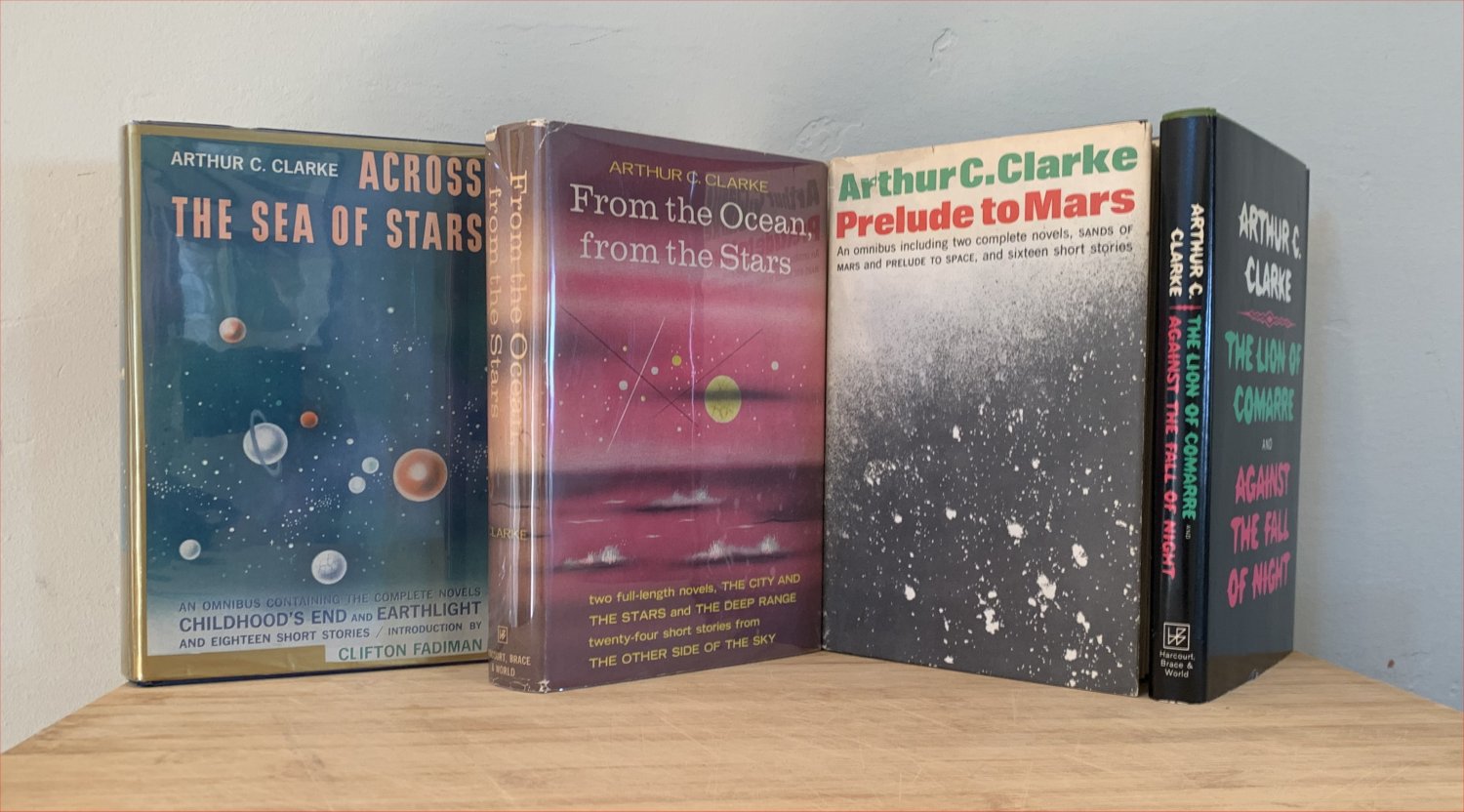

Arthur C. Clarke: Omnibuses, Collections, and Remixes

Omnibuses:

Across the Sea of Stars (Harcourt Brace World, 1959)

From the Ocean, From the Stars (Harcourt Brace World, 1961)

Prelude to Mars (Harcourt Brace World, 1965; book club edition shown)

The Lion of Comarre and Against the Fall of Night (Harcourt Brace World, 1968; book club edition shown)

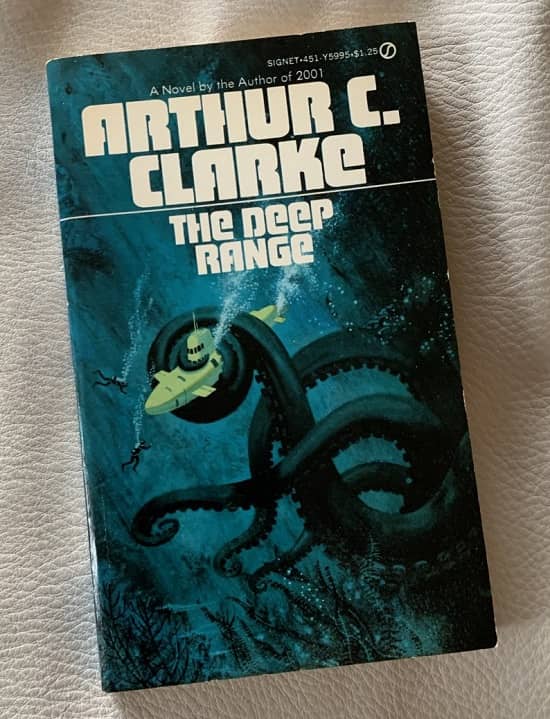

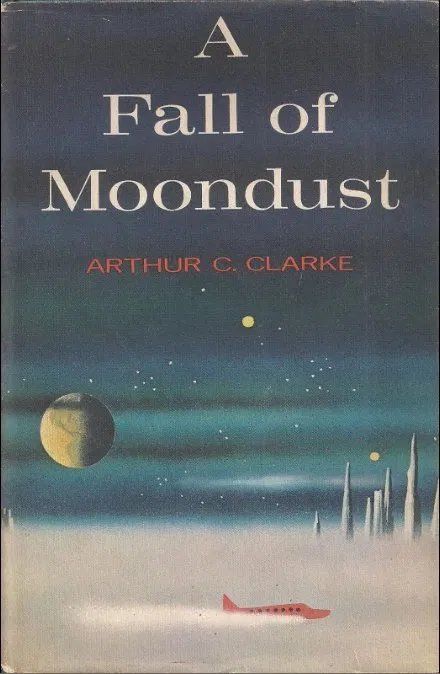

Arthur C. Clarke was one of the major science fiction writers of the 1950s through the 1970s; his biggest claim to fame was as coauthor, along with filmmaker Stanley Kubrick, of the film and novel 2001: A Space Odyssey. He was a British scientist who lived most of his life in Ceylon, later known as Sri Lanka, and wrote numerous books about his skin diving adventures in that area. He began publishing short stories as early as 1937, and his novels beginning in the 1950s included Childhood’s End, The City and the Stars, and Rendezvous with Rama.

This is the first of two posts about Arthur C. Clarke’s short fiction, which comprise nearly 100 titles and include such famous works as “The Star” and “The Nine Billion Names of God,” not to mention “The Sentinel,” one of the (several) inspirations for 2001. This post will trace the overlaps between Clarke’s early collections and the later “omnibuses” and “remixes.” The next post will review the stories, both in general terms and to highlight the 8 or 10 or 12 best, or most significant, Clarke stories, in my judgment.