Ellsworth’s Cinema of Swords: Mash-Up or Shut Up

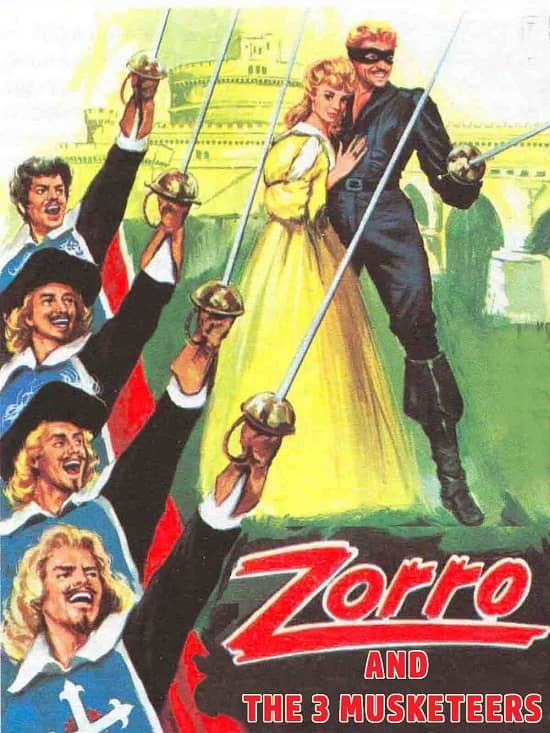

Zorro and the Three Musketeers (Italy, 1963)

Everyone likes crossovers and mash-ups, right? If you’re a fan of two heroes in the same genre, then of course you’d like to see a story in which they meet and confront a challenge together. That is the commercial calculation for crossovers in every medium, whether it’s comics, games, TV shows, or movies. It’s assumed a crossover or mash-up is a sure thing that will draw in the fans of both franchises. It’s a no-brainer.

In principle, maybe, but not in practice. In practice, the story or personality elements that create the appeal of one character don’t always fit comfortably with the elements of another. Zorro and the Three Musketeers, for example: all cheerful swashbucklers, but the musketeers are a disparate bunch that rely on teamwork, while Zorro is fundamentally a loner, so mashing them together in a coherent and credible plot is a task that shouldn’t be underestimated, calling for a top-notch screenwriter. Or what if you put together two characters like Yojimbo and Zatoichi, each of whom usually functions as the fulcrum of the plot? What do you do with two fulcrums? Solving these problems can be a high bar to get over, and sometimes a low-budget genre picture just isn’t up to it.

Though one has to admit, Zatoichi Meets the One-Armed Swordsman actually pulls it off.