When Howard first asked me–among several other Black Gate writers–if I would like to blog regularly for the web site, my first concern was about internet access. This was back in July, and I was soon to head off-grid for a yearly visit with my family in British Columbia, and after that to Dubai, where my spouse had taken a job, and where the government grants internet service only to those with residency visas, which he did not have yet. We didn’t get connected until the beginning of November. Fortunately, the web site wasn’t ready for us until the last few days! Now my concern, as a s..l..o..w writer, is generating content on a weekly basis…

At the start of a blogging endeavor it seems appropriate to introduce myself. I’m a writer of sf and fantasy whose academic background is in anthropology, oral literature, ethnolinguistics, and ethnohistory, and my geographic area of specialization is the indigenous north Pacific coast of North America. I post periodically about Dubai in my personal blog, and my website has a list of my fiction publications. Within the larger sf/f genre, I write all over the map, and at conventions I find myself on panels on shamanism and myth as often as those on the economics of space travel.

At such occasions and elsewhere I have witnessed much sub-genre bashing on all sides. I have also, when talking with people outside the genre, encountered more than my share of dismissive opinionating on the topic of sf and f in general (no doubt an experience shared by many readers of Black Gate) and, from within the genre, corresponding dismissiveness towards so-called mainstream fiction.

With regard to fantasy–the topic here–much of the bashing seems to come down to the view that the sub-genre is pathologically nostalgic, that it consists of little more than the endless recycling of the same tired cliches, and that writing fantasy is “easy,” in part because of its cliche-ridden nature and in part because in fantasy worlds, writers “can just make everything up.” There is, absolutely, too much fantasy that fits this stereotype. The topic of conventionalization in fantasy, however, is a much broader one that goes to the heart of how I think about genre, literature, and storytelling of all kinds, and I’d like to say just a few things about it in this first post.

One aspect of living in Dubai that I have not written about at my LiveJournal is the nature of communication here. Eighty percent or more of Dubai residents are expatriates from all over the world. English is the common language, but it is the first language of very few. Many people appear at first contact to speak English, but turn out only to be able to say or respond to a limited number of stock phrases, and much of the time will not tell you when they don’t understand you. Any transaction that deviates from the scripts they have memorized soon degenerates into chaos. I only wish I could provide a transcript of a call we made to Ikea Customer Service querying whether we had purchased the right kind of furniture treatment for our new put-it-together-yourself table. (I eventually realized that the transaction must have foundered over the term “unfinished furniture.”)

Having come up as a scholar through the study of unwritten languages and folk literature, I have a great respect for convention. All language, for example, depends upon shared conventions that govern how we parcel sounds and strings of sounds into meaningful categories. These rules do not determine what we say, but are rather the necessary tools for saying it.

Successful storytelling similarly depends upon many kinds of conventions, and from a folklorist’s perspective, all stories are examples of one genre or another. What distinguishes any given genre is its particular constellation of stock elements along with its rules for combining them. Moreover (I would add), every genre has its own bell curve of conventionalization, from the completely cliched and predictable to stories that are barely comprehensible within the genre’s framework.

Communications consisting purely of stock elements–between store clerk and customer, between writer and reader–can work, but only if the subject matter and the needs of the participants never vary. Outside of this very narrow frame, however, attempts at communication are at constant risk of disintegrating into meaninglessness.

Customer: Do we have the right finish?

Ikea Customer Service: You need to finish your furnitures, sir?

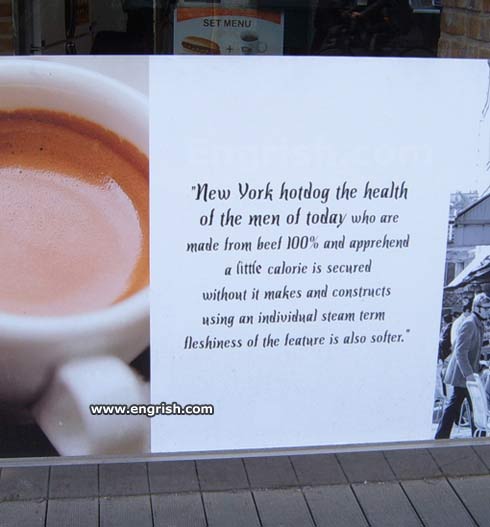

At the other end of the bell curve are communications that where the use of the relevant conventions is radically insufficient. These also can quickly descend into chaos. Take, for example, this sign (from Korea rather than Dubai) posted recently at that wonderful archive of under-conventionalized language, engrish.com:

Conventions, in other words, are not in and of themselves the enemy of literary value (howsoever that may be assigned) any more than the rules of English syntax and semantics are the enemy of comprehensible speech. Conventions are what make it possible for a writer to arouse the reader’s interest and to satisfy the reader’s expectations–to create meaning. As a reader, the most satisfying stories for me are often those that manage to find a middle ground and place conventions at the service of the unexpected. As a writer, my own creative process is often a dialectic between the raw power of convention to shape a story on the one hand, and my reaction to those conventions on the other, which often means wanting to tear them apart and reassemble them. A broad topic, as I said, and one I hope to come back to.