The Big Barbarian Theory

Conan, King Kull, Cormac, Bran Mak Morn — characters often imitated, never duplicated. These creations of Robert E. Howard started the sword-and-sorcery boom of the 1960s and early 1970s.

Conan, King Kull, Cormac, Bran Mak Morn — characters often imitated, never duplicated. These creations of Robert E. Howard started the sword-and-sorcery boom of the 1960s and early 1970s.

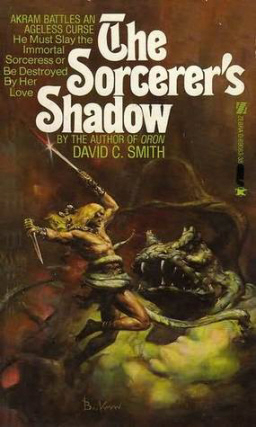

Then there are the barbarian warriors inspired by Howard — Clonans, as one writer recently referred to these sword-slinging, muscle-bound characters.

A fair observation, but in some cases, not so true.

We prefer to think of these tales of wandering barbarian heroes as “Solo Sword and Sorcery” because the majority of these characters are lone wolves, without sidekicks or even recurring companions. This is a big part of their appeal, in fact.

We’ve read many, if not most, of the Conan pastiches, including the novels based on Howard’s other creations. Karl Edward Wagner’s, Poul Anderson’s, and Andy Offutt’s portrayals of the Cimmerian come within a sword’s stroke of Howard’s vision.

L. Sprague de Camp and Lin Carter, in commodifying the character, arranged the long, informal saga of Conan in chronological order and, by extenuating these adventures with dozens more, made of Howard’s original vision a long-form series similar to the episodic success of a television show on a prolonged run of diminishing returns.

For some readers, however, the advantage of this development is that it provided a sort of character arc as Conan grows from a youth to an older man.

That said, however, it is better to read the Conan tales in the order in which Howard wrote them.