Dungeon Wishes

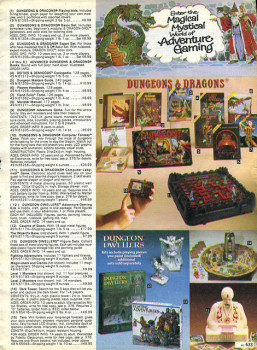

I first read a Dungeons & Dragons rulebook in late 1979, nearly six years after the world’s first roleplaying game had been released. Over the course of those years, a great deal had happened, both to D&D and to the wider hobby it spawned. While I hadn’t personally experienced all that had happened, my friends and I were beneficiaries of it all.

I first read a Dungeons & Dragons rulebook in late 1979, nearly six years after the world’s first roleplaying game had been released. Over the course of those years, a great deal had happened, both to D&D and to the wider hobby it spawned. While I hadn’t personally experienced all that had happened, my friends and I were beneficiaries of it all.

Looking back on the late 1970s from the vantage point of 2013, just days before the release of yet another big budget fantasy film, it’s sometimes hard to remember that fantasy – at least the peculiar kind of fantasy that D&D represents – was once a rather unusual taste. It certainly wasn’t yet the mainstream genre of entertainment it would become over the course of my lifetime, thanks in no small part to the success of Dungeons & Dragons. A few months before I discovered the game, Gary Gygax, in an editorial published in issue #26 (June 1979) of Dragon magazine, noted that, initially, he had assumed D&D would appeal only to a very small segment of the population. He writes:

The target audience to which we thought D&D would appeal was principally the same as that of historical wargames in general and military miniatures in particular. D&D was hurriedly compiled, assuming that readers would be familiar with medieval and ancient history, wargaming, military miniatures, etc. It was aimed at males.

He then goes on to say that, “Within a few months it became apparent to us that our basic assumptions might be a bit off target. In another year it became abundantly clear to us that we were so far off as to be laughable.” His larger point was that, because the game’s popularity had spread beyond college-age and older men with an interest in military history, the game itself would have to change to be more accessible to other potential players.

My 10 year-old self was one of those other potential players.