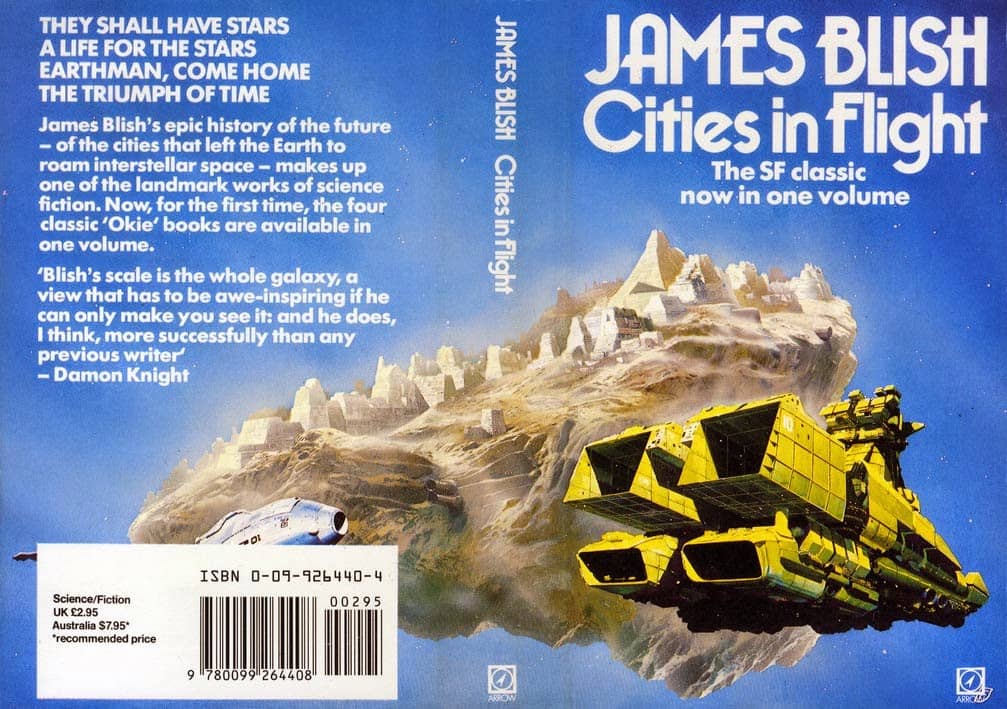

The Galaxy in Scale: James Blish’s Cities in Flight

There’s more windup than pitch in Thomas Xavier Ferenczi’s Tor.com column about Blish’s Okie series. But it’s someone writing about James Blish — not often seen these days.

I can’t exactly agree that these books are overlooked classics. They have a lot of the weaknesses and strengths of magazine sf at midcentury. They’re most interesting for their corrosive pessimism regarding democracy (as it is generally called), and their big-dumb-object sense of wild-eyed adventure. But the different parts of the fixups don’t work very well together; the world-building has inexplicable gaps; one gets tired of the characters out-wiling each other.

And gradually, in spite of all the repetition and confusion, the packrat crowding of irrelevant information, a symmetrical and moving story appears. Out of all the details in the book, some will be for you — not the same ones that hit me, very likely, but they will build up much the same impressive picture. Blish’s scale is the whole galaxy, a view that has to be awe-inspiring if he can only make you see it: and he does, I think, more successfully than any previous writer.

That’s from Damon Knight’s review of the core book in the group, Earthman Come Home. It was probably truer in the 1950s than it is now but, to the extent that it is still true, Cities in Flight is still worth reading.

I finally saw Spike Jonze’s Where the Wild Things Are a few days ago (because I’m never the first to see anything, as a matter of policy) and I thought it was pretty good. Some people have reacted with shock and horror to the violence and the scary bits, and maybe I’m over-reacting against them, but there wasn’t anything scarier in the movie than a regular kid might have to face in an average week. Which may, itself, be rather scary, but more so for adults and their illusions than for kids.

I finally saw Spike Jonze’s Where the Wild Things Are a few days ago (because I’m never the first to see anything, as a matter of policy) and I thought it was pretty good. Some people have reacted with shock and horror to the violence and the scary bits, and maybe I’m over-reacting against them, but there wasn’t anything scarier in the movie than a regular kid might have to face in an average week. Which may, itself, be rather scary, but more so for adults and their illusions than for kids. I’ve been guest-blogging (with fellow Pyr author

I’ve been guest-blogging (with fellow Pyr author