Pseudoplumes, Nom de Nyms, Birds, & Oooze: Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Language of the Night

|

|

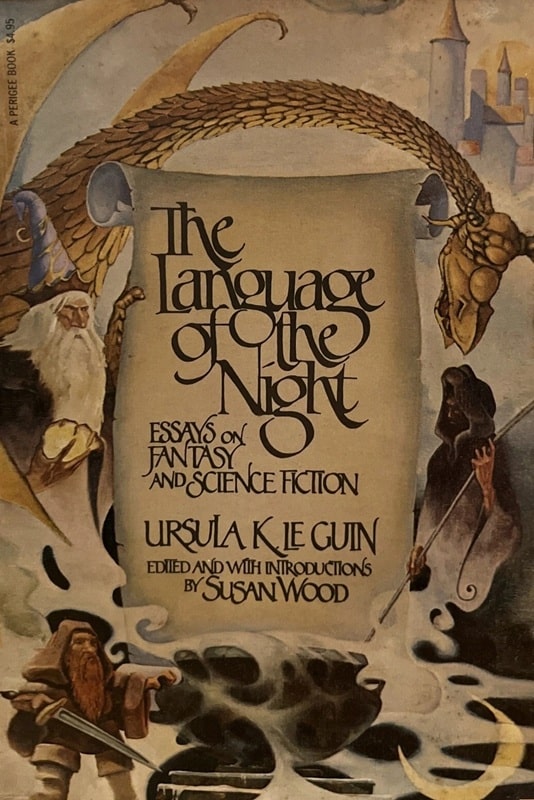

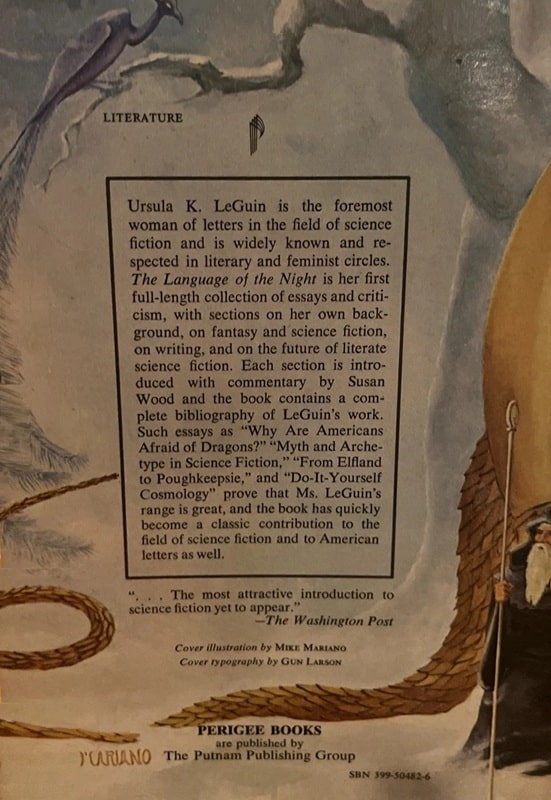

The Language of the Night: Essays on Fantasy and Science Fiction by Ursula K. Le Guin

(trade paperback reprint from Perigee Books, 1980). Cover by Michael Mariano

I’m not a big fan of literary criticism in any field (although I have committed some), but one of my big books from my late teens onward was Le Guin’s The Language of the Night (1979), especially for the essays “From Elfland to Poughkeepsie” and “A Citizen of Mondath.”

Le Guin has some great passages in “Citizen” about what she liked to read as a kid, and how she liked it.