A Review of The Outlaws of Sherwood, by Robin McKinley

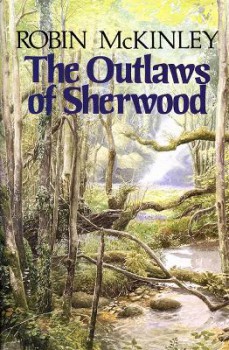

The Outlaws of Sherwood, by Robin McKinley

The Outlaws of Sherwood, by Robin McKinley

Greenwillow Books (282 pages, $12.95, 1988)

Cover by Alan Lee

“I am no historian,” Robin McKinley writes in the author’s note to The Outlaws of Sherwood, “and never flattered myself that I would write a story that was historically accurate. I did, however, wish to write something that was, let us say, historically unembarrassing.” I’m no historian either, but I’d say she succeeded.

The Outlaws of Sherwood is, of course, a retelling of the Robin Hood legend. It also feels extremely real, despite the historical issues mentioned in the author’s note. This is a good story for people who like a touch of logistics in their fiction. In between adventures — the book has a somewhat episodic feel, although it’s building up to a definite climax — there are plenty off details that highlight the problems and solutions to maintaining a covert community in a tangled forest.

Jhereg

Jhereg

I decided to review The Witches of Karres mostly because I remember seeing some sequels, written by different authors, as James H. Schmitz died in 1981.

I decided to review The Witches of Karres mostly because I remember seeing some sequels, written by different authors, as James H. Schmitz died in 1981. Jack the Giant Killer, by Charles de Lint

Jack the Giant Killer, by Charles de Lint Steve is a very normal man, perhaps even a bit boring. He works at an English shipping company, handling inventories and looking forward to a career in politics once he climbs the business ladder as far as it will take him. One day, for no particular reason, a sudden fit of discontent sends him down to the docks looking for something different, perhaps a restaurant he hasn’t visited. In an alley, he sees a man being attacked . . .

Steve is a very normal man, perhaps even a bit boring. He works at an English shipping company, handling inventories and looking forward to a career in politics once he climbs the business ladder as far as it will take him. One day, for no particular reason, a sudden fit of discontent sends him down to the docks looking for something different, perhaps a restaurant he hasn’t visited. In an alley, he sees a man being attacked . . . The Woman Who Loved Reindeer, by Meredith Ann Pierce

The Woman Who Loved Reindeer, by Meredith Ann Pierce The Ladies of Mandrigyn, by Barbara Hambly

The Ladies of Mandrigyn, by Barbara Hambly The Hero and the Crown by Robin McKinley

The Hero and the Crown by Robin McKinley The Door Into Fire, by Diane Duane

The Door Into Fire, by Diane Duane