Unempathic Bipeds of Failure: The Relationship Between Stories and Politics

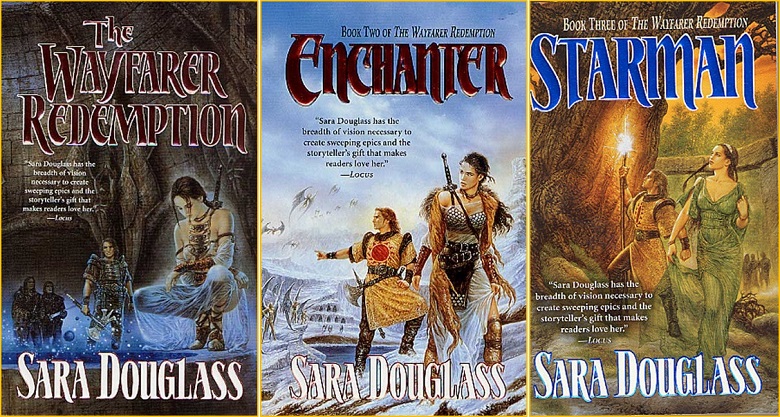

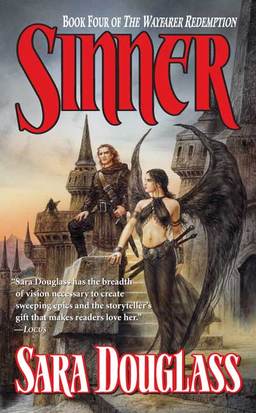

The Axis trilogy (published in the US as the first three novels of The Wayfarer Redemption)

Owing to recent political developments, I’ve been thinking a lot recently about politics in SFF, not just as a general concept, but in relation to my own history with the genre. So often when we talk about politics in SFF, it’s in the context of authors – rightly or wrongly, consciously or unconsciously, skilfully or unskilfully – conveying their personal views and biases through the text, the whens and hows of doing so and why it matters, depending on the context. As a corollary conversation, we also talk a great deal in personal terms about the importance to readers, and particularly young readers, of representation; the power of seeing yourself, or someone like you, in multiple sorts of narrative. These are all vital conversations to have, and to continue having as both culture and genre evolve. Yet for all its similar importance, I haven’t often seen discussions about the ways that SFF informs our concept of politics in the more institutional sense: the presentation of different systems of government, cultures and social systems within narratives, and the lessons we take from them.

Which is, to me, surprising, because as far back as I can remember, I was always aware of the role of politics in genre stories, even if I couldn’t always articulate that knowledge at the time. At the very start of high school, Sara Douglass’s Axis trilogy became my entry point to the world of adult (as opposed to YA or middle grade) fantasy. In hindsight, there’s a great deal in that series – and in the sequel trilogy, The Wayfarer Redemption – that I now find deeply unsettling, but which, as a tween, I absorbed uncritically. But at the same time, I also recognized the predatory, insular monotheism of Artor the Ploughman as a deliberate analogue to certain toxic expressions of Christianity, its displacement of and propagandising about the Icarii and the Avar reminiscent of lies told about various native populations by white invaders. I wasn’t yet literate enough to identify the racial stereotypes underpinning the Avar in particular – a dark-skinned race who claimed to “abhor” violence, yet were externally said to “exude” it – but something in that description still unsettled me; I remember feeling strongly that it was an unfair characterization in a way that went beyond the story, but couldn’t explain it any more than that.