Monthly Short Story Roundup – January

Well, it’s that time again, and here I am with another batch of new heroic fantasy and S&S short fiction reviews.

Well, it’s that time again, and here I am with another batch of new heroic fantasy and S&S short fiction reviews.

Nothing outside of Swords and Sorcery Magazine and Heroic Fantasy Quarterly caught my eye this past month and the stories they offered are the usual mixed bag, varying in quality from mid-range to very good. In a perfect world, some of these writers could make a living just writing short stories.

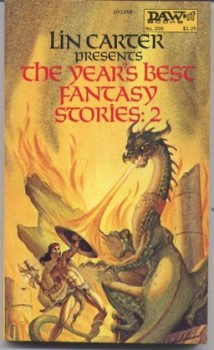

I love short stories. Growing up, a large part of my genre reading was made up of anthologies from brilliant editors like Lin Carter and Terry Carr. Their short (by contemporary standards) volumes introduced me to dozens of great authors, established and new.

In Lin Carter’s The Year’s Best Fantasy Stories: 2, for example, the authors ranged from Tanith Lee and Fritz Leiber to Caradoc Cador and Paul Spenser. If one story stunk, there was a very good chance the next one wouldn’t. It was a rare anthology that had nothing to offer.

In Lin Carter’s The Year’s Best Fantasy Stories: 2, for example, the authors ranged from Tanith Lee and Fritz Leiber to Caradoc Cador and Paul Spenser. If one story stunk, there was a very good chance the next one wouldn’t. It was a rare anthology that had nothing to offer.

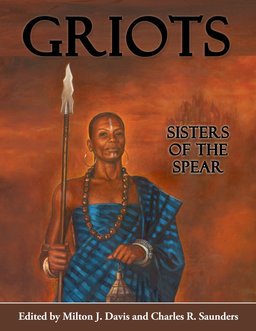

I’m not saying anything new when I say a ten- or fifteen-page story can be as powerful as a novel. I’d recommend Harlan Ellison’s “I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream” to anyone doubting that. As for excitement, how many five pound books can match the urgency and ferocity of Robert E. Howard’s “Beyond the Black River”? Sure, there are times I enjoy being swept up in a six- or seven-hundred page book, but I’d mostly rather read twenty or thirty good individual tales. When the rare new heroic fiction story collection comes along, like Strahan and Anders’ Swords & Dark Magic or Davis and Saunders’ Griots, I don’t hesitate to toss it in my Amazon cart.

And that’s why I love the various magazines (and the work their editors do each issue). Just counting Beneath Ceaseless Skies and Swords and Sorcery Magazine, I’m guaranteed at least six new stories a month. In the months Heroic Fantasy Quarterly is published, that’s an additional four or more.

Over the course of a year, that’s a lot more stories than even Lin Carter edited together in the same amount of time. Which makes me a very happy fan.