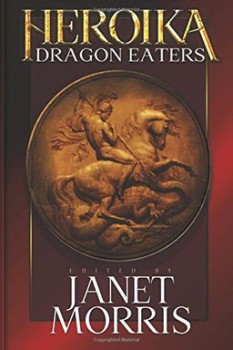

Heroika 1: Dragon Eaters edited by Janet Morris

For the past several months I kept seeing notices for the coming release of Heroika 1: Dragon Eaters. Edited by Janet Morris, one of the true heavies in heroic fantasy, and someone I have known online for several years now, I knew this was a book I was going to be reading. That its table of contents included several writers I’m a big fan of as well as many whose names I’m starting to hear good things about made it look better and better. That it’s about killing dragons sealed the deal. So when John O’Neill asked if I wanted to review it and I could have an e-book of it, I said “YES!”

For the past several months I kept seeing notices for the coming release of Heroika 1: Dragon Eaters. Edited by Janet Morris, one of the true heavies in heroic fantasy, and someone I have known online for several years now, I knew this was a book I was going to be reading. That its table of contents included several writers I’m a big fan of as well as many whose names I’m starting to hear good things about made it look better and better. That it’s about killing dragons sealed the deal. So when John O’Neill asked if I wanted to review it and I could have an e-book of it, I said “YES!”

I’m happy to report that with all that buildup, it’s a terrific bunch of stories. Anthologies are great because you can pick them up and dive in anywhere and take a short, rewarding excursion into whatever genre it is. I generally don’t read anthologies from cover to cover in a short period of time. Reading for this review it turned out I wanted a break from dragon-killing when I tried to finish the book in only a few big sessions. There are a few stories that aren’t to my taste, but there are no clunkers and some real treasures in this book.

The stories, and there are seventeen of them, are presented chronologically — well, the ones set in the real world anyway. Those set in more fantastical settings are fit in among the medieval ones. In the earliest tales dragons stand toe-to-toe with the gods. Slowly, they lose that stature and become mere monsters. Deadly, true, but no longer forces of raw, elemental chaos. Eventually they’re regarded only as mythical. In the future, scientific explanations have to be found for their existence.

Janet and Chris Morris’ “The First Dragon Eater” opens the book. Narrated by Kella, a priest of Tarhunt, it tells of the battles between the Storm God, Tarhunt, and the dragon, Illuyankas. Taken from Hattan myth, it’s probably one of the earliest tales of dragon-killing. The story’s style — formal sounding, as if something recited in a temple — lends gravitas to the introduction of the monstrous worms that figure in so many world myths and fantasy stories.

“Legacy of the Great Dragon” by S.E. Lindberg moves forward into ancient Egypt, as Thoth, physician of the gods, helps Horus to find power to avenge the death of his father, Osiris, at the hands of Set. This is a wild piece, with a cosmically huge dragon and gods fighting inside of it.