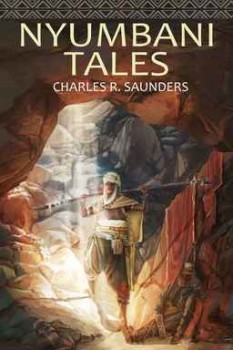

Stories from a S&S Griot: Nyumbani Tales by Charles R. Saunders

“I am going to tell a story,” the griot says.

“Ya-ngani!” the crowd responds, meaning “Right!”

“It may be a lie.”

“Ya-ngani.”

“But not everything in it is false.”

“Ya-ngani.”

The griot begins his tale.

from “Amma” by Charles R. Saunders

For those unfortunates unacquainted with Charles R. Saunders and the tales he’s woven, you can read plenty about them here at Black Gate. Suffice it to say he is called the father of sword & soul. Starting in the 1970s, he took the elements of swords & sorcery — mighty heroes, beautiful women, monsters, deadly magic, and more monsters — and turned them to his own purpose.

For those unfortunates unacquainted with Charles R. Saunders and the tales he’s woven, you can read plenty about them here at Black Gate. Suffice it to say he is called the father of sword & soul. Starting in the 1970s, he took the elements of swords & sorcery — mighty heroes, beautiful women, monsters, deadly magic, and more monsters — and turned them to his own purpose.

A fan of sci fi and fantasy growing up in the 1950s and 60s, by the time he graduated college in 1968, he was frustrated with a lot of what he was reading. As he recounted in an interview with Amy Harlib in The Zone:

I began to realise that in the SF and fantasy genre, blacks were, with only few exceptions, either left out or depicted in racist and stereotypic ways. I had a choice: I could either stop reading SF and fantasy, or try to do something about my dissatisfaction with it by writing my own stories and trying to get them published. I chose the latter course.

It was to the great benefit of heroic fantasy that Saunders made the choice he did. In addition to helping expand the horizons of the genre beyond the European settings that dominated it back then, he also created two monumental characters.

Imaro is the outcast warrior who eventually finds his destiny as champion against the forces of evil. Dossouye is an exiled warrior-woman from the kingdom of Abomey. The stories and novels featuring Imaro and Dossouye belong on the shelves of any S&S fan. If you haven’t read them yet, I suggest you snag copies of Imaro: Book I and Dossouye, clear off whatever else you’re reading, and get started.