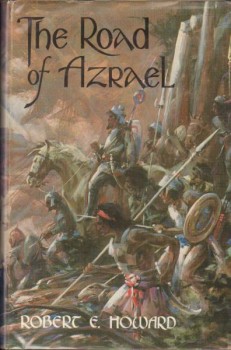

The Road of Azrael by Robert E. Howard

I can remember when my dad brought home The Road of Azrael (1979) and Sowers of the Thunder (1980), collections of Robert E. Howard’s historical adventure tales. My reading tastes were so exclusively fantasy and science fiction then, I couldn’t imagine wasting any time on boring, mundane stories. No wizards, no demons? What the heck was anybody thinking?

I can remember when my dad brought home The Road of Azrael (1979) and Sowers of the Thunder (1980), collections of Robert E. Howard’s historical adventure tales. My reading tastes were so exclusively fantasy and science fiction then, I couldn’t imagine wasting any time on boring, mundane stories. No wizards, no demons? What the heck was anybody thinking?

I grew out of that attitude a few years later and read both volumes. I remember liking them, but if you asked me for details on either one, I couldn’t have told you a thing. I read them once and never again. In fact, until recently I hadn’t read any other historical adventure even though, theoretically at least, I was a fan. I mean, it’s one of the primary root sources of swords & sorcery. At a very basic level, Robert E. Howard took the historical adventures of writers like Harold Lamb and Talbot Mundy and added magic and monsters.

It wasn’t until I started blogging about swords & sorcery and started getting all sorts of recommendations for the stuff that I looked into the genre again. With my review of Henry Treece’s The Great Captains four years ago, I started including some novels in my writing for Black Gate. I’ve been including a taste every month or so (most recently Purity of Blood by Arturo Pérez-Reverte), and it’s gone over well.

One of the pledges I made to myself at the start of my Black Gate tenure four years ago, was to avoid the big names of swords & sorcery. No one, I felt, needed another article about Michael Moorcock, or Fritz Leiber, or especially Robert E. Howard. Considering I wrote about Karl Edward Wagner’s Night Winds for my very first full review, THAT promise didn’t last very long, but I have tried to keep my focus on lesser-known or forgotten authors in my reviews of older works. Since then, I’ve reviewed a Moorcock book, a new one by Charles Saunders, and several more Wagner books, but until now I’ve steered clear of REH (especially because Bob Byrne has done a terrific job writing about him here at BG in his ongoing Discovering Robert E. Howard columns). It’s too hard to completely avoid the foundational figures of swords & sorcery when writing as often as I do, but I try to keep it to a minimum.

All this is a complicated way to say I’m reviewing The Road of Azrael by Robert E. Howard, and feel fully justified in doing so. It collects five historical tales of varying quality.

The paperback edition I read has execrable cover art, which did nothing to add appeal for me. Fortunately, the first thing in the book is a laudatory introduction by Gordon Dickson, no slouch of a storyteller himself, praising REH’s storytelling talents. Not that I need reminding of just how good Howard could be, but it’s always nice to see him get the praise he deserves. Unfortunately, I did not like the opening story, “Hawks Over Egypt.”

![a-wizard-s-henchman-hardcover-by-matthew-hughes-[3]-3997-p](https://www.blackgate.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/a-wizard-s-henchman-hardcover-by-matthew-hughes-3-3997-p-251x350.jpg)