Half a Century of Reading Tolkien, Part Seven: The Sword of Shannara by Terry Brooks

Ten years ago to the month (I started this in October), I wrote about Terry Brooks’ groundbreaking The Sword of Shannara (1977), and declared that the joy I got reading the book the first time around was something I couldn’t recapture. Time had opened a gap between the book and what I could take away that seemed uncrossable. Revisiting the book, yet again, I no longer think that’s completely true, but it’s not entirely false.

Ten years ago to the month (I started this in October), I wrote about Terry Brooks’ groundbreaking The Sword of Shannara (1977), and declared that the joy I got reading the book the first time around was something I couldn’t recapture. Time had opened a gap between the book and what I could take away that seemed uncrossable. Revisiting the book, yet again, I no longer think that’s completely true, but it’s not entirely false.

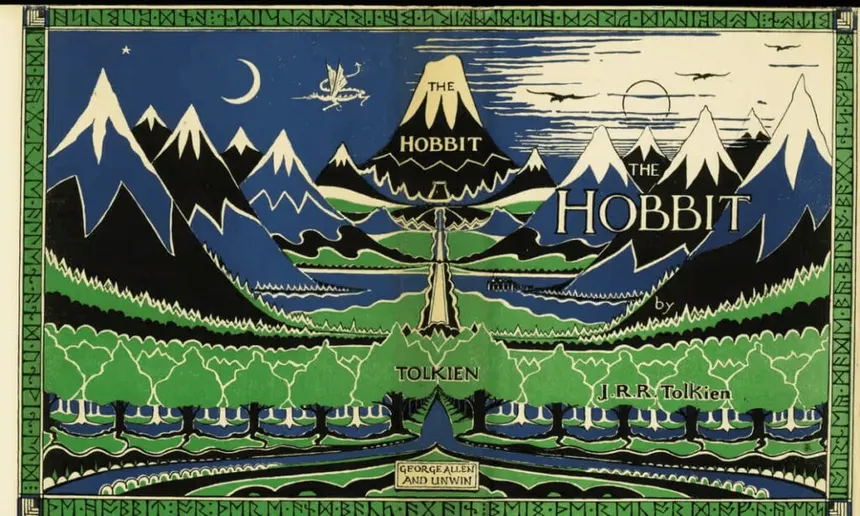

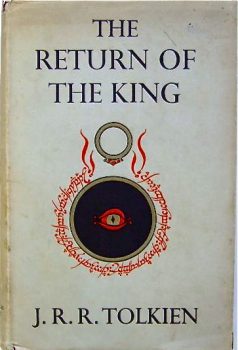

When I set out earlier this year on my journey through Tolkien’s writing, I decided to mix it up with several works clearly inspired by Tolkien, and particularly the Lord of the Rings. Bored of the Rings (reviewed here), was my first choice because it’s an explicit parody of the trilogy (and a brilliant one!).

Sword was an easy choice, as well, even if its origin story is complex and was touched by divers hands (well, six, to be precise, between Brooks and the Del Reys). I’m not sure Brooks set out to write a story that tracks so closely to the LotR in so many places, but that was result. It kicked off the mass-market success of quest trilogies featuring secret heirs in search of the foozle needed to bring down the Dark Lord in his isolated redoubt.

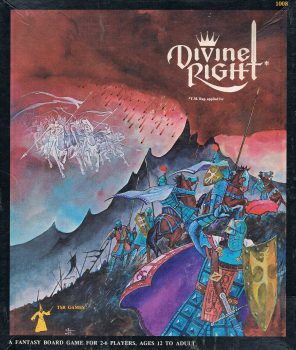

In the summer of 1981, my friend Alex R. had moved into a big, new house not far from the Staten Island neighborhood where most of my other friends lived. As his parents were rarely home and summer was beginning, we spent all our days and most nights there, watching movies and playing D&D. Things changed significantly when George K. showed up one day with a copy of TSR’s fantasy wargame,

In the summer of 1981, my friend Alex R. had moved into a big, new house not far from the Staten Island neighborhood where most of my other friends lived. As his parents were rarely home and summer was beginning, we spent all our days and most nights there, watching movies and playing D&D. Things changed significantly when George K. showed up one day with a copy of TSR’s fantasy wargame,