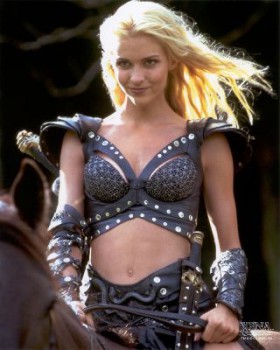

Ancient Worlds: Callisto and Arcus

The problem with gods isn’t just that they’re terrible parents, or that they’re bad luck to be around. Greco-Roman gods were bad news because, well, they were people. Which sounds nice and relatable until you think about some of the people you know.

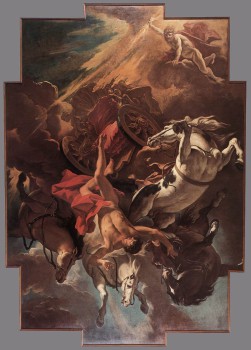

They’re intense, passionate beings who are untempered by immortality. Which means they feel everything we feel – love, joy, anger, jealousy – but with the powers of a god to back them up.

This is most apparent in the stories of Zeus (Jupiter in Ovid’s works) and his many…. Well, some older editors call them “loves”. Some others call them “conquests”, which is a little better. For the most part, they’re victims, either of Zeus when he kidnaps them or his wife when she finds out about them.

One such victim whose story Ovid tells is Callisto. She was a sworn virgin, a friend of Diana who wandered with her in the wilderness. She spent all her time with her fellow virgins, hunting, fishing, and generally avoiding men and the role usually allotted to young women in the ancient world. Until Jupiter saw her and raped her. As if that weren’t bad enough, when she was discovered to be pregnant, Diana threw her out of her company.