Lovecraft in China: The Flock of Ba-Hui by Oobmab

|

|

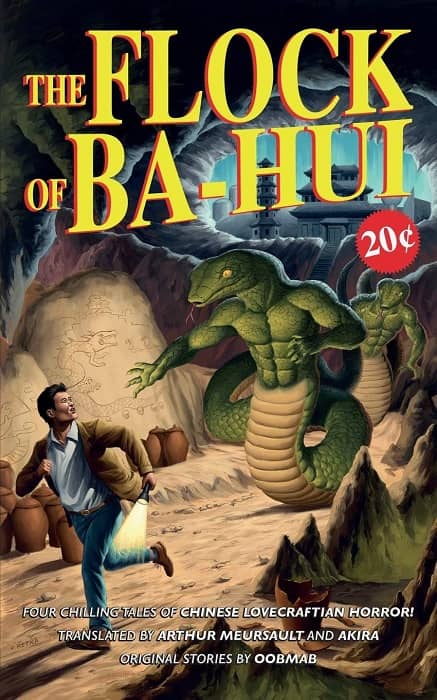

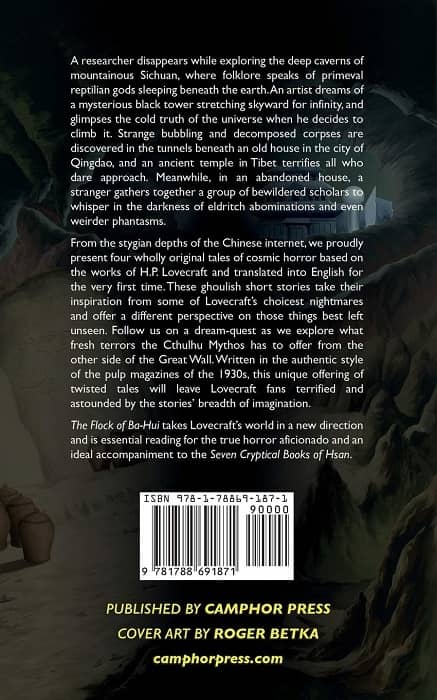

Cover by Roger Betka

The Flock of Ba-Hui and Other Stories

Oobmab (translated by Arthur Meursault and Akira)

Camphor Press (254 pages, $24.99 hardcover/$14.99 paperback/$6.99 digital, February 2020)

Beyond the protective barrier of Europe’s vast libraries, Latinate languages, aristocratic bloodlines, and imperial armies, there lurks a malign chaos of ancient knowledge and alien science. To our Western eyes, this chaos is a universe of black magic and monsters but there is, alas, much more to it than that, when one considers the full span of inhuman evil that extends from ancient creatures long outcast, brooding and breeding sinister vengeance in the Earth’s depths, to the latest incursions by loathsome entities whose blasphemous technologies have carried them to this green and innocent planet from the mist-shrouded globes circling the farthest stars.

This is essentially Lovecraft country: a universe that has become known as the “Cthulhu Mythos.” Ever-fearful of dark forces from the outside, in daily life the American author H.P. Lovecraft (1890-1937) was an enthusiastic exponent of modernity – the expansion of northern European cultures throughout the world to the disadvantage, even appropriation, even erasure, of indigenous and non-European cultures. As America itself blossomed into an imperial power, Lovecraft’s United Empire loyalism (which to be fair, was greatly mitigated in his later years) envisioned a USA that “must ever remain an integral and important part [as he wrote at age 24] of the great universal empire of British thought and literature.”

Born in Providence, Rhode Island, Lovecraft treasured his native New England not only for its green fields, stone churches, and stately mansions, but for the ways these things embodied the culture of an even-more-native England, a just and civilized seat of a white, English-speaking empire, an island across the sea that he felt linked to in spirit, although he never saw it in person.