An Abhorred Monster: Frankenstein by Mary Shelley

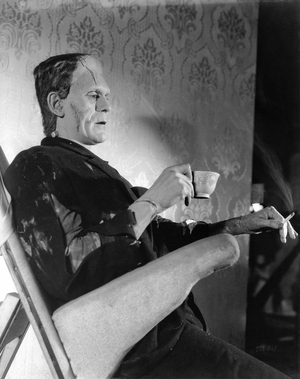

Like most people these days, my first encounter with the patchwork creature from Mary Shelley’s novel, Frankenstein (1818), was through adaptation. I truly cannot remember whether it was a moulded plastic Halloween mask, a comic strip, James Whale’s 1931 movie Frankenstein, starring Boris Karloff, or Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948) that I saw first. Which one doesn’t matter — that green-makeup-painted face with flat head and neck bolts was an image that was everywhere: comics, cartoons, a giant statue on top of a bar & grill on my hometown of Staten Island. In each case, Victor Frankenstein’s creation was presented as a lumbering, platform-booted monster. At some point, I learned that Shelley’s was a very different creature than that which Whale had created for the screen, but that knowledge was unable to dislodge decades of Whale’s iconic image.

While normally presented as a horror story — and there are great, horrific elements in the book — it is really one of the first science fiction novels. Victor Frankenstein is a warped version of the Enlightenment man, rejecting the supernatural entirely, pursuing material and empirical knowledge to the point “no man was meant to know”. The Creature, foreshadowing countless androids and cyborgs, is tormented by the question of his standing in the universe as a man-made being. I thoroughly enjoyed this terrific, if slightly flawed, book.

I imagine most people know the basic story of Frankenstein‘s creation. As part of a storytelling contest between herself, her lover, the poet Percy Shelley, the poet Lord Byron, and Byron’s sidekick, Dr. John Polidori, eighteen-year-old Mary Shelley conjured a scientist obsessed with creating life. The poets’ tales were never finished, but Polidori wrote one of the first vampire tales, “The Vampyre” (1819). Shelley’s idea was potent enough to turn into a full-length novel.

I saw the pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together. I saw the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine, show signs of life, and stir with an uneasy, half vital motion. Frightful must it be; for supremely frightful would be the effect of any human endeavour to mock the stupendous mechanism of the Creator of the world.

Mary Shelley from her introduction to the 1831 edition of Frankenstein

The novel is made of three separate narratives nested within one another. The first is that of an Englishman, Robert Walton, leading an expedition to the North Pole. Trapped in the ice, he and his crew spy a strange sight:

We perceived a low carriage, fixed on a sledge and drawn by dogs, pass on towards the north, at the distance of half a mile; a being which had the shape of a man, but apparently of gigantic stature, sat in the sledge and guided the dogs. We watched the rapid progress of the traveller with our telescopes until he was lost among the distant inequalities of the ice.

Later, another traveler appears on the ice, but instead of continuing on, asks permission to come aboard. We learn this polar wanderer is a Swiss scientist named Victor Frankenstein and he has a tale to tell, which he does for several chapters.

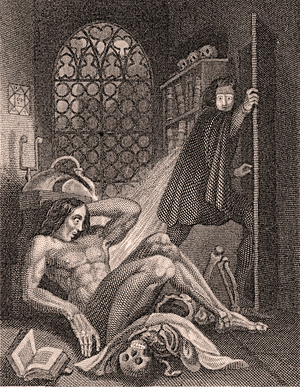

Frankenstein was first inspired by various ancient philosophers, alchemists, and the like. But when he attends the University of Ingolstadt he is converted wholeheartedly to actual, empirical science. He becomes obsessed with creating life, but when he does he is horrified by the result:

It was already one in the morning; the rain pattered dismally against the panes, and my candle was nearly burnt out, when, by the glimmer of the half-extinguished light, I saw the dull yellow eye of the creature open; it breathed hard, and a convulsive motion agitated its limbs.

How can I describe my emotions at this catastrophe, or how delineate the wretch whom with such infinite pains and care I had endeavoured to form? His limbs were in proportion, and I had selected his features as beautiful. Beautiful! Great God! His yellow skin scarcely covered the work of muscles and arteries beneath; his hair was of a lustrous black, and flowing; his teeth of a pearly whiteness; but these luxuriances only formed a more horrid contrast with his watery eyes, that seemed almost of the same colour as the dun-white sockets in which they were set, his shrivelled complexion and straight black lips.

Frankenstein abandons his creation, rushing out into the night. When he returns to his lab the next day his creation is gone. Soon, death begins stalking his family. His little brother is murdered, seemingly by an orphaned girl his family had taken in as a maid, and she is to be executed. Returning home, Victor sees something in the night:

… I perceived in the gloom a figure which stole from behind a clump of trees near me; I stood fixed, gazing intently: I could not be mistaken. A flash of lightning illuminated the object, and discovered its shape plainly to me; its gigantic stature, and the deformity of its aspect more hideous than belongs to humanity, instantly informed me that it was the wretch, the filthy dæmon, to whom I had given life.

The third narrative is the Creature’s. Though he’s attempted to make friends, he is too monstrous and was attacked and driven away. Enraged at a man who would create him and them leave him totally alone, the Creature came to Geneva to confront him. Unintentionally, he kills Frankenstein’s brother, but intentionally, in a moment of pure malice, he frames the maid. He then confronts Frankenstein and demands he assemble a similarly-visaged female companion for him or he will kill more of the scientist’s family.

For the rest of the novel, Frankenstein and the Creature fight a battle more philosophical than physical. Can the Creature convey with enough logic and passion his misery over his societal isolation and his need for a patchwork Eve? Can Victor Frankenstein, believing such a path could only lead to humanity’s destruction, resist his handiwork’s seemingly just demands?

“Be calm! I entreat you to hear me before you give vent to your hatred on my devoted head. Have I not suffered enough, that you seek to increase my misery? Life, although it may only be an accumulation of anguish, is dear to me, and I will defend it. Remember, thou hast made me more powerful than thyself; my height is superior to thine, my joints more supple. But I will not be tempted to set myself in opposition to thee. I am thy creature, and I will be even mild and docile to my natural lord and king if thou wilt also perform thy part, the which thou owest me. Oh, Frankenstein, be not equitable to every other and trample upon me alone, to whom thy justice, and even thy clemency and affection, is most due. Remember that I am thy creature; I ought to be thy Adam, but I am rather the fallen angel, whom thou drivest from joy for no misdeed. Everywhere I see bliss, from which I alone am irrevocably excluded. I was benevolent and good; misery made me a fiend. Make me happy, and I shall again be virtuous.”

Frankenstein is a novel about alienation. The Creature didn’t ask to be made but he was, and by a creator who immediately rejected him. He is desperate for an ounce of compassion from Frankenstein but is denied. His evil — and his bloody crimes are evil — is as the outbursts of an abandoned child, lashing out in rage at the world and his deity. This rage, expressed so eloquently (how he became so articulate is one of the book’s flaws), is an anguished howl to God that can fail to move only the most hardhearted. Even his murderous actions sound justified when he describes them.

Shelley’s first three children all died before or during the writing of Frankenstein and her sister committed suicide a month before she started. Surrounded by death as she was, it does not seem unbelievable that such spiritual trauma would lend great depth to her portrayal of the Creature’s despair and outrage against the universe.

Frankenstein is ultimately the story of dueling tragic characters, bound together as two sides of a coin. The Creature is a man standing against the world and his Maker; Frankenstein is his maker. Both are driven to terrible ends by their own awful actions as much as by their actions against each other. Frankenstein will create life out of death and the Creature will have his way. Each should walk away, but neither will; they are inevitably drawn to each other and to doom. In the end, the deadly trek across the Arctic ice seems the only possible outcome there ever could have been.

As noted earlier, Frankenstein isn’t flawless. All three narrators sound remarkably similar. Whether a wealthy Englishman, a Swiss scientist, or a bundle of revivified graveyard scraps, each speaks in a most elevated style with great introspection and filled with literary and philosophical allusion. How the Creature comes to speak like this — by listening in on the education of a young Arabian girl that includes such works as Plutarch’s Lives, Sorrows of Werter, and most importantly, Paradise Lost — is ludicrous. There are several chapters, little more than travelogues, that could easily have been excised with no detriment to the novel. None of these things, though, are more than minor distractions. The worth and power of Mary Shelley’s book derive from her novel ideas, her romantic prose, her ill-omened characters, and the struggle between Creator and Creation.

Frankenstein, I suspect, will, alas, remain more an icon than a book people actually read. James Whale and Boris Karloff (and make-up artist Jack Pierce) did their work too well, which is a pity. Like the Creature, Shelley’s novel is a darkly brooding work that howls and rages at a callous world in a way that is still compelling.

The version illustrated by the late, great Berni Wrightson is the best representation of the look and feel of Shelly’s work in my opinion. It was a labor of love for him and it shows. His pen and ink work did more to cement a non-hollywood esthetic to the creature and environments, even though he clearly loved the films.

Please check out Sundays with Frankenstein on Facebook. It is a weekly discussion of the novel sponsored by the Rosenbach Museum in Philadelphia. We are on chapters 3-4 (1818) this week.

Thematically it’s a very rich novel that’s rather a rough read, which makes it the opposite of Dracula, which isn’t nearly as deep but is an absolutely ripping ride.

Fletcher, this is a wonderful post. I did not know that Shelley was experiencing the death of a child and a sister during her writing.

@rtorno – I’ve never read the whole thing, but what I’ve seen, like most everything by Wrightson, is astounding.

@David P. – That sounds fun, thanks for the info

@Thomas P. – My hope is to get to Dracula later this year. I started it once and saw exactly what you mean.

@Seth – Thank you! Along with the dislocation of having moved to Italy for Percy S.’s health which might have lead directly to two of those children’s deaths and Percy’s continued infidelities.