A Great Fantasy Poem: “Winter Solstice, Camelot Station” by John M. Ford

|

|

|

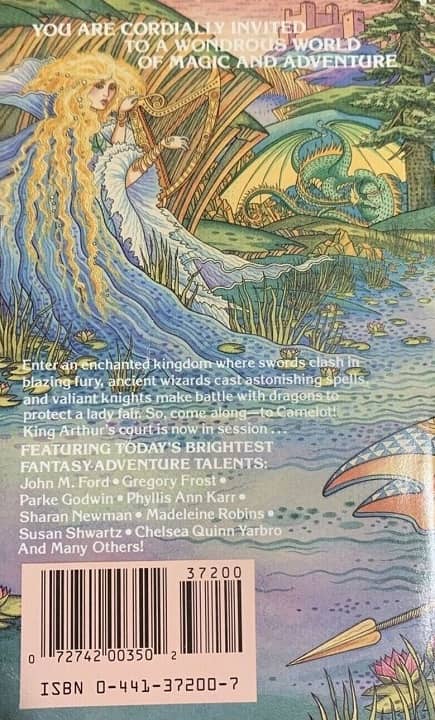

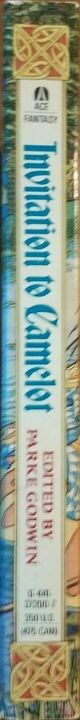

Invitation to Camelot, edited by Parke Godwin (Ace Books, 1988). Cover by Jill Karla Schwartz

This is the latest of a series of essays I’m doing to give an extended look at SF stories I consider particularly good, or particularly interesting, with some intent to try to tease out how they work, why they work. And this time I’ve decided to look not at a story, but a poem! But never fear – it’s an exceptional poem, and it’s also a no doubt work of Fantasy, traditional Fantasy, one of the most familiar Fantasy subjects – with also a descriptive veneer of Science, of Industry, of Engineering.

I am a devoted reader of poetry… favorite poets include Wallace Stevens, Philip Larkin, and W. B. Yeats; more recently, A. E. Stallings. But I have to confess general disappointment with most of the poetry published within the SF/Fantasy genres these days. There are exceptions, though: I’ll name Sonya Taaffe as a particular favorite just now (and I’ll recommend the small ‘zine Not One of Us, where Taaffe is a regular, as a particularly good source of contemporary SF/Fantasy poetry.) In a slightly earlier time, there was another master: John M. Ford. His-best known poem is probably “Winter Solstice, Camelot Station”, and it’s perhaps my favorite poem to have been published in a genre source.

I once understood that it originated as a Christmas card Ford sent to friends in 1988. But actually it was first widely published earlier in 1988, in the anthology Invitation to Camelot, edited by Parke Godwin. (I’ve asked for confirmation of the date of the Christmas cards, with the notion that perhaps they came out in 1987, but Chuck Rothman, who received one, is quite sure it was in 1988.)

[Click the images for Camelot-scale versions.]

|

|

|

Assorted issues of Not One of Us: #8 (Oct 1981), #22 (Sept 1999), and #61 (March 2019)

Ford as a writer was always clever. Sometimes the cleverness overwhelmed the story, but more often the cleverness was in service of the story; and his stories, even when drawing attention by the tricks he played, resolved into pieces of great power, often very moving. I wonder sometimes if part of his lack of great financial success during his life could be attributed to his work being unfairly dismissed as merely clever. I’m not sure that’s really the explanation (great writers have failed to make the money they deserve for a long time, after all!)

“Winter Solstice, Camelot Station” is a poem that can be described as “clever” – imagine Camelot with trains! And make sure your poem has both neat Arthurian references plus playing on the industrial age! – but it’s also a poem that resolves to be both beautiful and moving.

|

|

Heat of Fusion and Other Stories by John M. Ford (Tor Books, 2004). Cover by Shelley Eshkar

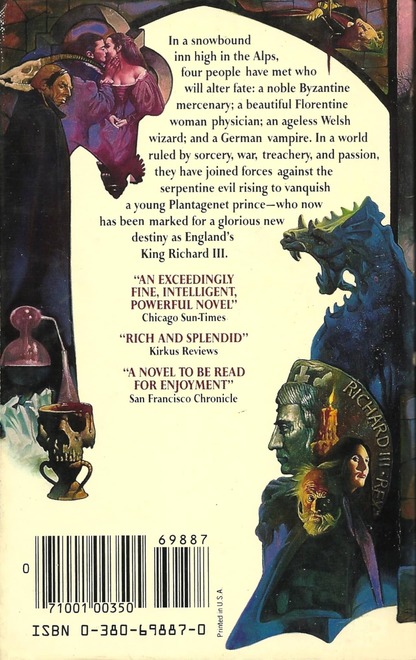

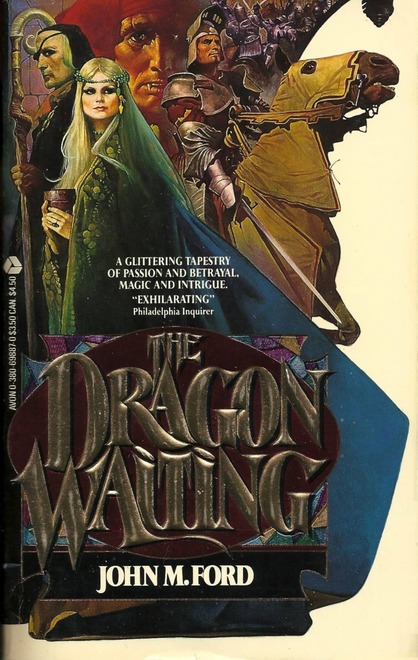

I have the poem in his collection Heat of Fusion. It’s also been anthologized in a number of places, including Ellen Datlow and Terri Windling’s Year’s Best Fantasy: Second Annual Edition. It won both the World Fantasy Award for Best Short Fiction and the Rhysling Award for Best Long Poem in 1989. As many know, Ford’s books have been generally hard to find since his death, due to agent problems, apparently; and to some confusion on the part of his heirs. But these issues have been resolved, and his work is beginning to come back to print, beginning with the classic novel The Dragon Waiting, which was reissued by Tor last September.

|

|

|

The Dragon Waiting by John M. Ford (Avon, 1985). Cover by Sanjulian

“Winter Solstice, Camelot Station” opens with a description of the station itself:

a sixteen-track stub terminal done in High Gothick Style,

The tracks covered by a single great barrel-vaulted glass roof framed upon iron,

At once looking back to the Romans and ahead to the Brunels.

I love that last touch, placing it both in time (after all, Arthur (if he existed) came after the Romans left, but long before the Industrial Revolution and the great civil engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel (whose father and one of his sons were also civil engineers), but also hints at the ambiguity of time in the whole poem, with the reference to High Gothick style.

Then Sir Kay, the seneschal, shows up in his Range Rover, ready to welcome the Knights back to Camelot for the Solstice celebration. Again – there’s the cleverness, almost flippancy, of the reference to the “Range Rover.” (So too the references to such Knightly deeds as “rescuing maidens tied to the tracks,” or to the “Old XCVII, The Fast Mail overnight to Eboracum.”) But for all the cleverness the references land… the time-binding, or perhaps “unbinding,” is part of it – this is Camelot, but it’s also us. And Kay’s character is nailed absolutely (“half Falstaff, half Hotspur”), in a few brief lines.

Then come the Knights. Bors, “sword on his hip swinging like siderods at speed” – a perfect simile, and impossible in any other context. Pellinore, with the Questing Beast in a crate… and another joke that lands, him blaming Gutman and Cairo for cheating him. And he doesn’t stomp on the joke.. so I won’t either. But it’s not just a joke – it’s another beautiful allusion. Palomides is presented as Middle Eastern, arriving on the Orient Express, with “a woman in Chanel black, a glint of diamonds, liquid movements, liquid eyes,” who manages to evade the “newshawks” (Camelot’s paparazzi).

Galahad seems to have a private silver train: “golden hair… Armani tailoring, just the sort of man you’d want finding your chalice.” And then these lovely lines:

A space in which he shifts like sun on water;

Look quick and you may see a different knight,

A knight who knows that meanings can be lies,

That things are done not knowing why they’re done,

That bearings fail, and stainless steel corrodes.

That’s Galahad, but it’s the whole Round Table too, and the description, marrying timeless imagery with the last perfect line playing on the integuments of trains.

Of course “Mordred and his car are both upholstered in blue velvet and black leather.” He’d rather have flown but had to take the train. “The premature lines in his face are a map of a hostile country, The redness in his eyes a reminder that hollyberries are poison.” On a freight track we meet another man coming, greeted by two “ugly men.” The three head in, and “the one who is King says “It all seemed so simple, once,”/And the best knight in the world says “It is. We make it hard.””

And then it’s the Solstice celebration.

The wassail will be hot and the goose will be crackling

All that sackbut and psaltery stuff

The young knights will dally and the damsels dally back,

The old knights will play poker at a smaller Table Round.

So – the station has welcomed the Knights. The celebration is on. And behind the scenes, still, the trains are running, the station working, and this is how the poem closes:

The nerves of the kingdom, the lines of exchange,

Running to a schedule as the world ought,

Ticking like a hot-fired hand-stoked heart,

The metal expression of the breaking of boundaries,

The boilers that turn raw fire into power,

The driving rods that put the power to use,

The turning wheels that make all places equal,

The knowledge that the train may stop but the line goes on;

The train may stop

But the line goes on.

So why does this work? And how? Some of this is the old secrets of poetry: imagery, and sound, or rhythm. The sword swinging like siderods, old Bors a pelican on a rock, Palomides dripping Soubranie ash on his astrakhan collar, the woman with him and her liquid movements, liquid eyes, Galahad shifting like sun on water… The rhythm is easy and rapid – like a train, the language essentially demotic (though elevated when needed), and the sound and structure is poetry, not prose, despite the lack of rhyme, and the uneven lines.

Yeats wrote:

A line will take us hours maybe;

Yet if it does not seem a moment’s thought,

Our stitching and unstitching has been naught.

I have no idea of course how long it took Ford to write this poem, but it flows as easily as if every line was indeed a moment’s thought.

Then too there is what I’ve already mentioned: the mixture of modern engineering imagery with references to the Matter of Britain: back to the Romans, ahead to the Brunels. There are in-jokes throughout, nods at Arthurian minutiae (Gawaine exchanging a glance with a “chap in green”) or train lore (the Old XCVII, the Orient Express, the B&O.) Some of this is funny, some is pointed.

There are also “story values,” mainly characterization: we get a feel for each of the Knights in just a few lines. Kay is perhaps the best realized, “thick,” “practical,” “stolid,” concerned that his Knights in training remember to tip the porters, aware that trains can be late but not happy about it. But little touches abound with each of the characters… Gawaine and his brothers with their self-wrapped unicorn head (their Mum did the rest of their packing)… Arthur and Lancelot meeting as friends, Lance singing “Wenceslas”… Mordred’s private DC-9 with video system and Quotron and waterbed…

And, finally, the serious matter. Trains and tracks and Knights and a King engaged in uniting a country, running a country, “to a schedule”… and behind all this the readers knows that it will all fail, the dream will die, the country fall to war within itself, everyone betrayed. Still … “the train may stop,/But the line goes on.”

Previous articles in this series on SF stories include:

An Evocation of the Science Fiction Dream of Exploration: “The Star Pit” by Samuel R. Delany

Alien Eggs, a Diligent Salesman, and a Robot Psychiatrist: Three Stories by Idris Seabright

Rich Horton’s last article for us was Alien Eggs, a Diligent Salesman, and a Robot Psychiatrist, a review of three stories by Idris Seabright. His website is Strange at Ecbatan. Rich has written over a hundred articles for Black Gate, see them all here.

I do love that cover.

Makes me think of Charles Williams’ Arthurian poetry in Taliessin Through Logres and The Region of the Summer Stars, especially that bit about “lines of exchange.”

I just read The Dragon Waiting and loved it so I’ll be looking out for more Ford if its all as good as that and this poem.

I was thrilled to see the focus on this spectacular poem–truly one of the best in the genres. While this is not a metrical poem per se, there’s great interplay between prose lines and lines of iambic pentameter and hexameter. The section on Galahad almost resolves into beautiful blank verse as well. Thank you, Rich!