Fiction Excerpt: “Seijin’s Enlightenment”

By William John Watkins

Illustrated by Matt Hughes

from Black Gate 9, copyright © 2005 by New Epoch Press. All rights Reserved.

Senjin had a good deal of blood on his hands when he walked the road between Edo and Gojin. The blood did not bother him, because it was Samurai blood, honestly gotten at the risk of his own, and he was on his way to spill more blood in Gojin. The Champion of the Lord of Gojin was waiting for him there. It was said by many that the Champion of the Lord of Gojin was Death himself. But Senjin did not believe it. When he was finished in Gojin, Senjin planned to go on to Kyoto, where his lord had another quarrel.

Senjin had a good deal of blood on his hands when he walked the road between Edo and Gojin. The blood did not bother him, because it was Samurai blood, honestly gotten at the risk of his own, and he was on his way to spill more blood in Gojin. The Champion of the Lord of Gojin was waiting for him there. It was said by many that the Champion of the Lord of Gojin was Death himself. But Senjin did not believe it. When he was finished in Gojin, Senjin planned to go on to Kyoto, where his lord had another quarrel.

He sat quietly at the fringe of the light, a tall, gaunt, serious-faced man, while the other travelers sat closer to the fire. Four were Samurai and three of those were young; the fourth was as old as the two merchants who sat together nearest the fire. The older Samurai sat further back from the flames, leaving himself room to maneuver both in front and behind. He sat opposite the young Samurai, who did not leave enough maneuvering room between themselves and the flames. And although the old Samurai looked relaxed, Senjin was pleased to see that he used the eyes of the young men for mirrors to see behind himself.

After they ate, the three older men told stories of the great fighters they had heard of. One spoke of the Champion of the Lord of Gojin, who was thought to be Death himself, but the other two spoke of Senjin. And though he did not smile, it pleased Senjin inwardly that his skills were spoken of with respect. But he was proud for practical reasons. If the stories of his battles spread widely enough, he would have no trouble founding a school when he was too old for fighting, though he doubted that such a day would come. Still, as his skill had grown, his zeal for combat for its own sake had diminished, and of late he had felt an uneasiness for which he could find no practical cause.

It always disturbed him when he could not find a practical cause. Unlike other Samurai, he did not believe in any mystical dimension to what he did. He did not think of himself as a dead man, as did many Samurai, so that he could commit himself to strike without fear of the consequences. He struck without fear, but only because clarity of thought made the opportunity to strike clearer and created fewer mental errors that might lead to death or injury.

He did not believe, as other Samurai, that only the fearless man could strike the fatal blow. He himself felt fear whenever the sword was drawn, but he did not succumb to his fear. He put it aside, and concentrated on the practical aspects of the fight, finding his opponent’s weaknesses, creating an opportunity to exploit a weakness, striking quickly and precisely. For him, careful observation and meticulous planning were more important than fierce courage or philosophical enlightenment. Good technique, he was sure, was worth more than the best philosophy.

It amused him that the men who spoke of him spoke of his dedication to the sword, as if its use were a way to spiritual knowledge. It was a popular myth, but he did not subscribe to it. He was a pragmatist, not a holy man. For him, the sword was a tool, like the carpenter’s hammer his father had taught him to use. Its use was a craft, not a religion. Sensibly applied, it could provide a livelihood. Nothing more, nothing less.

He kept silent when he heard the stories, but not because he was humble. He was a practical man, and even though he was at the height of his form, it was unwise to declare himself. To do so was to invite attack. One of the young Samurai, seeking instant fame, was bound to challenge him, and die.

As likely as not, the young man would have friends around the same fire, or relatives nearby, or even relatives far away who would sit opposite Senjin around some other fire, knowing him, while he did not know them. And then they would inevitably seek revenge and have to be killed, which would only create more men with a reason to kill Senjin. Or the young Samurai might have a mother or a sweetheart somewhere along the road, who would cook a meal for Senjin in which the poison could not be told from the seasoning.

The prudent thing to do was to avoid killing, except in professional matters. And even there, the prudent thing to do was kill as little as possible. It was not that Senjin had any great respect for human life, other than his own. He had no qualms about killing. It was his livelihood, his profession, and he was very good at it.

But because he was the champion of a great lord, his fights were public. Other Samurai saw him fight, and he knew that great as his skill was, his technique had its weaknesses. If watched carefully often enough, those weaknesses would be apparent, and another Samurai like himself might find a way to exploit them. The prudent thing to do was to fight sparingly, in widely separated places, and to get every fight over with quickly.

Even when the stories were finished, and one of the young Samurai stood up and said he would put Senjin in his place if only he were here, Senjin said nothing. Unlike other Samurai, who bristled at the least provocation, he did not feel it was possible to be insulted by a fool. Anyone who insisted on killing fools was going to get arm-weary long before he reached the last one. So Senjin sat quietly on the outskirts of the firelight and said nothing.

The older Samurai cautioned the younger one, but the younger one insisted that he feared no man and Senjin least of all. The older Samurai only shook his head, and shrugged in Senjin’s direction, and Senjin knew he had been recognized. He knew also that he would not be able to avoid a fight.

He knew that the old Samurai had recognized him from the beginning, and had been moving him in the direction of killing the young Samurai ever since. They were both pawns in the old Samurai’s game. The story was meant to goad the young Samurai into some foolish boast. The boast was meant to force Senjin into killing him.

Senjin admired the practicality of it. The young man was hotheaded, but apparently skilled, and the old Samurai knew he would have to fight him sooner or later and probably thought he was not certain to win. Senjin suspected the young man had powerful relatives the old Samurai did not want to have to contend with. A fatal encounter with Senjin offered the perfect solution.

Goaded by the old Samurai, the young one made boast after boast, and when the old man praised Senjin’s skills, the young one derided them. Inevitably, he passed on to insulting not only Senjin’s reputation but his ancestry. When he said that he would humiliate Senjin before he killed him, the old Samurai said, “Well, there is your chance,” and pointed to Senjin.

Senjin was standing by then, still half in the shadows, but he knew there was no escape. If the young Samurai backed down, the older one would only goad him into a quarrel. If Senjin did not declare himself, the old Samurai would only laugh at the young one for being frightened of a nameless stranger. There was no walking away from it now, even for Senjin. If he walked away from such insults, even young Samurai, who avoided any hint of confrontation with him, would be made bold to challenge him. For Senjin, the choice was fight once then, or fight dozens of times later on. The only reasonable thing to do was fight.

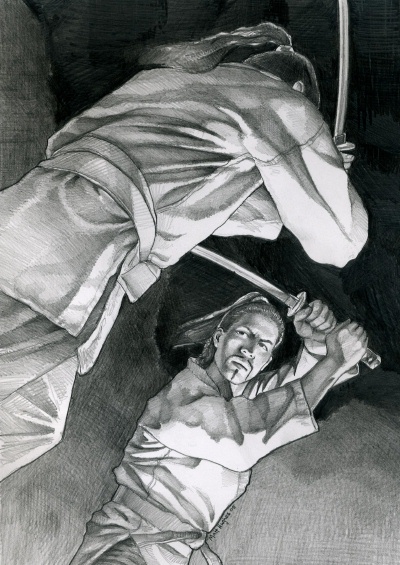

When the young Samurai demanded to know if his name was Senjin, he had no choice but to say that it was, and the young Samurai had no choice but to fight. Without preliminary, he drew his sword and attacked. It was a foolish maneuver, and Senjin sidestepped him easily and opened him across the body from hip to armpit. When the young man tried to twist his body, he simply came apart.

The other young Samurai sat with their mouths open. Senjin took three little steps closer to the old Samurai. “Did your lord put you in charge of these men to get them killed?” he said. The old Samurai’s eyes squinted and his hand moved toward his sword, but before his fingers could touch it, Senjin’s sword sliced through his topknot just above his scalp. The hair fell at his feet, still tied together. Senjin crouched and picked it up. Before the old Samurai could react, he was back in fighting position. “When I do another man’s work,” Senjin said, “I expect to get paid.” He tucked the hair into his belt and walked away into the darkness.