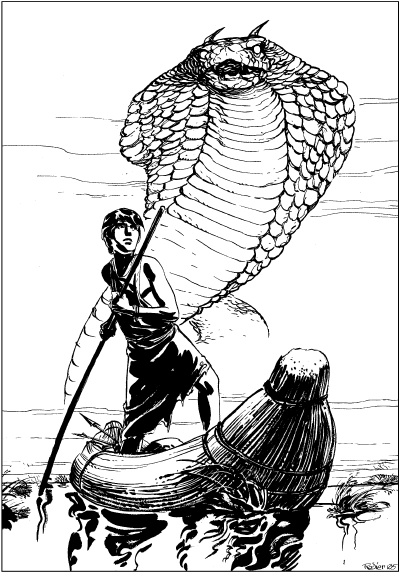

Fiction Excerpt: “The Longday Hunt”

By Sean Oberle

Illustrated by Denis Rodier

from Black Gate 9, copyright © 2005 by New Epoch Press. All rights Reserved.

Silently chewing on a piece of dried fish from the pouch at his hip, Jace guided his potanakra through the swamp, steering as much with his hips as with the paddle. The small craft was the main transport of his people — a length of simply woven reeds about the thickness of a man’s forearm, molded with a slight depression at the rear just wide enough to kneel in. The front usually rode out of the water unless the driver put a heavy load there. Although a potanakra had always reminded Jace of a cupped hand with the fingertips scrunched together so they came to a point, Kevra said the name meant “water spider” in the ancient high tongue. That made sense to Jace: riding high in the water, a potanakra skimmed across surface like a water spider. Right now Jace’s skimmed very well because he carried only his spear, laid in front of him to grab and cast in one quick motion.

Silently chewing on a piece of dried fish from the pouch at his hip, Jace guided his potanakra through the swamp, steering as much with his hips as with the paddle. The small craft was the main transport of his people — a length of simply woven reeds about the thickness of a man’s forearm, molded with a slight depression at the rear just wide enough to kneel in. The front usually rode out of the water unless the driver put a heavy load there. Although a potanakra had always reminded Jace of a cupped hand with the fingertips scrunched together so they came to a point, Kevra said the name meant “water spider” in the ancient high tongue. That made sense to Jace: riding high in the water, a potanakra skimmed across surface like a water spider. Right now Jace’s skimmed very well because he carried only his spear, laid in front of him to grab and cast in one quick motion.

Kevra’s daughter Lally was why Jace was here, or at least part of the reason. Really, it had to do with the Longday Festival. Jace was hunting serpent, just like all the village boys old enough to have their first whiskers but younger than their seventeenth Longday — 23 boys in all this year. Next week’s Longday would be Jace’s last as a boy.

Kevra was the village’s Keeper. Fifteen years before Jace was born the previous Keeper, Kevra’s Aunt Feena, had chosen him to leave the swamp and travel to Spadra for the learning. Kevra knew when Longday and Shortday and the Sunturns occurred. He kept the count for the Shadowings, when the moon ate the sun. He knew all the ancient tales and traditions. Kevra said that this Longday would be special — indeed, many villagers had lived and died and not seen one so special. A Shadowing and Longday would happen on the same day. It was a very strong omen, said Kevra, avoiding answering when the Council asked, “strongly good or strongly bad?”

Whether good or bad, thought Jace, whichever of us can bring home a serpent under this omen will surely be great … maybe even head the Council, the first man to do so in generations. Jace pushed away the thought that regardless of the omen, this was his last chance to harvest a serpent, and he’d had more chances than most. Because his birthday came in the spring, his wiskering came before his twelfth Longday — many boys did not get to hunt until their thirteenth or even fourteenth Longdays. This would be Jace’s fifth chance. Not every year brought a serpent. Indeed, it had been seven years since Rafe had brought back a serpent.

The Longday Hunt determined who among the boys would sit on Council when they became men and thus determined whom they could marry. Council members only married other Council members. That last part was what worried Jace the most. Lally, even at a year younger than Jace, already had secured herself a future spot on the Council, though Jace did not know how — the women kept their methods a secret from all men except Kevra, and he wasn’t telling. It was unfair, Jace always thought. The girls knew how and why the boys rose to the Council, but the boys didn’t know the same about the girls. If Jace did not get a place on the Council this year, he could never marry Lally. Perhaps he’d even have to take a wife in another village elsewhere in the swamp or even beyond. That thought as much as the fact that every firstborn in his family had been Council members for generations motivated him.

The water rippled to the right of his potanakra, near a tuft of reeds, and Jace spun the boat to a quiet stop, the spear in his hand and the paddle laying in front of him before the spin stopped. To Jace, using the potanakra was as natural as walking, and the boat came to a rest pointing almost directly at the ripple, a little off center, but close enough that only someone from one of the villages would have noticed. He peered at where the ripple almost had disappeared.

Whatever it was, it was long — too long for most fish, and any fish long enough would have been too big to maneuver in these shallows. If it had been that long, but wider, Jace would have considered a school of smaller fish, but it was narrow. Fish did not swim in single file like goslings following their mother through the village. No, this was a serpent. Jace knew the signs. Every boy tracked serpents year round whenever they got the chance. Harvesting a serpent out of Festival might be forbidden, but tracking was not. All fathers taught their sons to track serpent, even fathers who were not on Council — maybe especially those fathers.

Where the ripple had been, another began, and Jace’s eyes widened as the tail of a serpent broke the surface for just an instant. The scaly tip was as big as his hand. Serpents that large did not travel together, and the time between the first ripple and the second meant that it had to be at least fifty to sixty hands long. Omens indeed, thought Jace as he spun the boat to pursue.

Peering in the direction the serpent had gone, scanning in widening arcs the farther his vision got from the last ripple, as his father had taught him, Jace soon saw a ripple to the left of center. The serpent was turning into the Dank.

Jace had been into the edge of the Dank a few times, but never beyond sight of an entrance and never off a main stream. Kevra told stories about the Dank and how people got lost in there and faced who knew what death. Jace even had known one person who might have died in there — the last time anyone saw old, unmarried Smid eight planting seasons earlier, he was paddling in the direction of the Dank, hunting duck eggs. The whole village knew he got the best duck eggs, and many people had whispered that Smid knew of a place inside the Dank where the ducks nested free of bothersome people.

The Dank, instead of being a maze of reed tufts like the rest of the swamp, was a clog of short trees only about twice a man’s height, stunted and ugly unlike the few shade trees and the Festival Tree on the village’s island. The upper branches hung down and wove themselves among the branches of nearby trees, making a canopy that in some places was barely above the head of someone in a potanakra. The bases of the trees were all in shallow water, maybe waist deep, and roots poked up everywhere. The villagers called them “the old mens’ knees.” Kevra frowned on anyone who even dared to enter, but he said that venturing off a main stream or even out of sight of an entrance could be deadly. After a few twists and turns, he warned, the trees all look alike, and when trying to come back out, it was easy to turn at the wrong tree and become hopelessly lost.

The serpent’s back rippled the water again, and Jace was certain it was going into the Dank. That made sense, he supposed. The biggest serpents would be in the Dank.

He would chance it. Maybe he could catch it before it went too far in or left the main stream. Surely, he thought, such a huge serpent with a Shadowing on Longday would win him a great honor along with a seat on the Council… and Lally.

He paddled harder and soon he was crossing under the first trees. Instantly, it became darker, but not cooler like it should have been in the shade. If anything, it was hotter, and already he could smell the rotting that sometimes blew out of the Dank into the village. It was sweeter than the dun pile behind the village, but it was a rotting smell all the same.

Again the tail broke the surface. It still was too far away for Jace to risk throwing his spear, but the serpent looked to be heading straight up the stream. The water flowing out sluggishly was about the width of three or four potanakras, and the branches were higher and less woven than elsewhere. A few sunrays even came through, their shafts ending in small circles of light shining on the top of the water.

Soon Jace was farther in than he’d ever been, and a quick glance behind showed him that a slight curving of the stream already had hidden the entrance. But he still could see the difference between the stream and the rest of the Dank — the leaves in the stream moved towards the entrance, and the stream’s water was not covered with a thin film of yellow-green scum, as it was elsewhere.

The noises were changing. The bugs and frogs were chirping like it were night, and off to either side, it might as well have been dusk it was so dark. And the bugs were not just noisy. They buzzed around his head, and Jace resisted the urge to swat at them lest he make a splash and alert the serpent. Kevra never said anything about the bugs being worse in the Dank, but Jace decided he could stand a few itchy lumps to get the serpent.

The next time the serpent broke the water, the ripple was closer — the tail couldn’t be more than a few lengths of the potanakra ahead. But the serpent was still heading straight up the center and at the same pace. If it knew Jace was following, it wasn’t concerned.

Jace was concentrating so much on looking just ahead for the ripples in the dim light he did not notice at first that there was sunlight ahead. When he did, he wondered, Have I gone all the way through? He’d circled the Dank many times, and he knew there was no way that he’d navigated clear through the center, but the Dank sent out arms in places, and maybe the stream had bent into one of them and he’d come out. If so, he was not where he imagined himself to be.

But when he reached the opening, he saw it was a clearing, maybe big enough to hold twenty huts, about half the size of the village. Slightly off center was a small islet that looked to be made of piled rocks. Another ripple told him that the serpent was heading toward it. As he approached, he saw its surface area was about five or six times that of his potanakra.

The serpent’s head emerged from the water near the islet, and it climbed the rocks to disappear near the center; it looked to be going into a hole. Jace laughed silently as the serpent’s body kept emerging from the water. Indeed, it was a long one. Sixty hands might have been a small guess. It still looked like it was unaware of being tracked.

Jace slowed his craft as he approached the islet and bumped silently against it. As he tied the potanakra, he noticed that the piled rocks were tooled to rough rectangles and some still were held together with mortar. Below the waterline, they still made a wall — or rather four walls. The rocks were not piled, he decided, they had fallen there. A structure once had risen above the water, and Jace wondered how many other stones lay beneath the water around the islet. That would give him a sense of how high it had been, but he could not see more than a few hands into the muddy water.

Climbing softly onto the rocks, spear pointed before him defensively, Jace slowly raised up to look where the serpent had disappeared. It was a hole, roughly square, and there were steps. “You’re a fool,” he whispered to himself as he placed his foot on the first step. Shortly, he was far enough down that there was a ceiling above him. It too was made of cut rocks mortared together.

Jace paused for a moment to let his eyes adjust to the light, and he noticed that he already was feeling cooler, just like the coldhouse dug in the center of the village. After another few steps, he began to hear the plip-plink-plip of water dripping into water. That made sense, Jace thought. Kevra said it was the pool in the floor of the coldhouse that helped to keep it cool enough to slow food from spoiling.

Soon Jace reached the last step, and he found himself facing a large stone statue of a serpent. It was mostly curled up, but its front end was raised as if to strike, and Jace estimated it at more than 100 hands long. Between him and the statue was a square pool of water, the brim raised with a single row of stones just above the floor. Water dripped from the ceiling into the pool. Small rocks littered the floor. He quickly scanned the room, but did not see the real serpent.

He also did not see any other exits, even holes in the wall. “There’s nothing so dangerous as a cornered serpent,” he almost could hear his father warn.

“A fool, indeed,” he sighed and took a single step into the room.