Fiction Excerpt: “The Hand That Binds”

By Michael Livingston

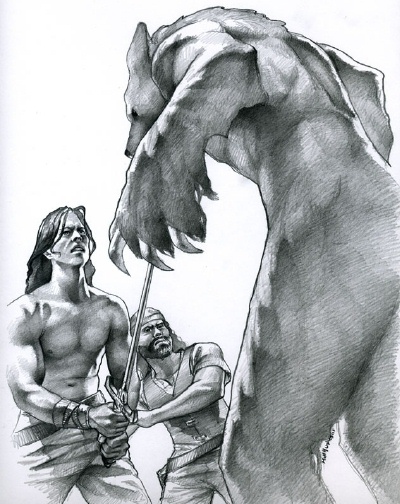

Illustrated by Matt Hughes

from Black Gate 9, copyright © 2005 by New Epoch Press. All rights Reserved.

Heorot was a buzzing hive of noise and activity when Widsith arrived. Hrothgar had ordered a feast set for his guests, and the community had gathered together under the leaking timbers to join in the celebration. The king’s entire household was assembled along the benches lining the back of the hall, and Hrothgar himself sat on his time-beaten throne at the center of his family, holding court as if he owned the hall once more. A surface appearance, but Widsith knew that such things counted for much among these people. They were taught never to back down, never to admit defeat. Hrothgar’s people would not openly acknowledge his waning strength any more than they would openly discuss the hideous creature that prevented their king from spending a night in his own hall. But their refusal to acknowledge the truth did not change it. The simple fact was that the king of the Danes was old before his time, beaten into submission by more than the passing of years: the loose and wrinkled skin, the tattered, threadbare robes, and the sparse locks of thin, hoary hair did not speak of the once great warrior-king of the Danes – a king that had not existed since the shadow-fiend had come to Heorot. But they did not admit his failing. True, there were whispers among the people. It was said that Hrothgar could no longer lift his sword; it was said that he could no longer even summon the strength to mount a steed. But they would never admit such doubts, even if all could see that he was a broken warrior, unable to combat the single, terrifying beast that slowly and inexorably destroyed his kingdom. It took only the briefest of glances for Widsith to see that even now Hrothgar was fighting hard to remain straight-backed upon his throne, fighting to conserve what little dignity and pride remained in the house of the Danes. A dying people.

Heorot was a buzzing hive of noise and activity when Widsith arrived. Hrothgar had ordered a feast set for his guests, and the community had gathered together under the leaking timbers to join in the celebration. The king’s entire household was assembled along the benches lining the back of the hall, and Hrothgar himself sat on his time-beaten throne at the center of his family, holding court as if he owned the hall once more. A surface appearance, but Widsith knew that such things counted for much among these people. They were taught never to back down, never to admit defeat. Hrothgar’s people would not openly acknowledge his waning strength any more than they would openly discuss the hideous creature that prevented their king from spending a night in his own hall. But their refusal to acknowledge the truth did not change it. The simple fact was that the king of the Danes was old before his time, beaten into submission by more than the passing of years: the loose and wrinkled skin, the tattered, threadbare robes, and the sparse locks of thin, hoary hair did not speak of the once great warrior-king of the Danes – a king that had not existed since the shadow-fiend had come to Heorot. But they did not admit his failing. True, there were whispers among the people. It was said that Hrothgar could no longer lift his sword; it was said that he could no longer even summon the strength to mount a steed. But they would never admit such doubts, even if all could see that he was a broken warrior, unable to combat the single, terrifying beast that slowly and inexorably destroyed his kingdom. It took only the briefest of glances for Widsith to see that even now Hrothgar was fighting hard to remain straight-backed upon his throne, fighting to conserve what little dignity and pride remained in the house of the Danes. A dying people.

Widsith counted fifteen of the Geatish men: all young, all banded together at a mead-bench in the middle of the hall. They smelled of the sea. At the head of their table, facing Hrothgar’s throne, sat a giant of a man whose braided flaxen hair hung in loose and dirty tangles about his shoulders. Widsith watched him for long seconds, noting the confidence in his manner and the sheer physical power that seemed to exude from him. A powerful warrior. Young, but powerful.

The tall Geat reminded him for a moment of the iron fist of Eormanric, but he forced such thoughts and memories away. He had no time for memories of her to come flooding back. Not now. Instead, he looked about the room and spied Wulfgar, an elder warrior whom he had grown to trust during his time among the Danes. Like the bard, Wulfgar was an outsider who had been welcomed into Hrothgar’s dwindling household. The Danes turned few away these days. They could not afford to.

Still keeping an eye on the visitors, he made his way through the crowd toward his fellow outsider, greeting many of the Danes along the way. When he finally reached Wulfgar’s side, the warrior met him with an amused and knowing grin. “Good morning, Wealth-watcher. You slept well, I trust?”

Widsith smiled at the epithet. He had come to the Danes penniless and hungry, a beggar with songs and an instrument. “You mustn’t allow me so much mead,” he said. “You should know better by now.”

“We know your weakness for the honey-jug all too well, Widsith. But your stories are better when you are drunk.”

Widsith nodded, forcing a blush to allow the older man to have fun at his expense. “What do these Geats want?”

Wulfgar’s smile faded. “They want to eat for now,” he said. “Then they want to kill the night-walker.”

Widsith blinked. “Kill him? They’ve come from the north only to fight the beast?”

“Yes. And they are mere boys, most of them. Anxious to win glory for their lords, and acclaim from ones such as you.”

“Ah, do not blame the bard for the headstrong nature of youth, my friend. The tale always proceeds the teller.” And don’t blame me for the folly of pagans and their demons.

Wulfgar grunted, then nodded in the direction of the Geat sitting at the head of the table. “Though that one is no boy,” he said.

The big Geat was, indeed, far from physical childhood. Even sitting he appeared to be a head taller than his companions, and his body looked to be thick with slabs of strength. But there was something else, a coldness perhaps, that made Widsith uneasy in his bones. “What is his name?”

“He is the leader of the company, and most eager for fame,” Wulfgar said. “He is Beowulf, son of Ecgtheow of the Wylfings who was brother-in-law to Hygelac, lord of the Geats. They come in the Geatish lord’s name on behalf of all Geats, though Beowulf’s father was known to Hrothgar in the old days. The Danes paid the wergild of the Wylfing Heatholaf for the exiled Ecgtheow, allowing him to live.” Wulfgar frowned. “I think Beowulf means to repay the family-debt by killing the Grendel.”

With practiced ease, Widsith took in the information, catalogued it, put it away in the back of his mind. “More victims for the corpse-stalker,” he said. And a waste of a strong warrior. This one has the look of a second Offa, who won his kingdom with a single stroke of his great sword.

“There is hope, bard. There is always hope. The soul-ravens might not come tonight, and these Geats may survive to see the dawn.” Wulfgar spoke strong words, but Widsith had been among the Danes long enough to know the emptiness of such things. They were a broken people, without hope. All they had left were numbered days. All is death here. A dying folk. A dying way of life.

Widsith moved away through the crowd like a watch-spirit, listening to the whispers of the Danes as they admired the visitors. They were impressed with the Geats, of course — impressed as they would be with any visitors to their monster-stricken hall — but they clearly marveled at Beowulf. Some of them remembered tales of a swimming match — a duel of some sort — between Beowulf and a rival. There were vague rumors of how Beowulf had swum the whale-road to prove his manhood, how he had fought and killed many beasts of the deep upon the waters. The bard was not surprised to hear others talk of hope now that the Geats had come, talk of how they might defeat the mere-walker that had destroyed the spirit of the Danes. But even faced with the imposing Beowulf, it was tired talk. The Danes had seen their best come and go. And they had raised many pyres to would-be heroes who had meant to cleanse Heorot of its curse. But those were Danes, some said. This man is a Geat.

There was also quieter talk of the Danish princes who so paled in comparison with the visiting warrior. Though they would not speak openly of it, the Danes knew that Hrothgar was an old man, powerless to stop the beast. And they knew that the princes were too weak to stand alone before rival claimants to the throne — much less against the monster in their midst. But in Beowulf they saw power, and this, too, did not surprise Widsith. The bard, a man of history, knew how tenuous the mortal grip on authority could be.

As he was slipping among the Danes, Widsith saw Aethel on the other side of the Great Hall. Like the others, she was staring at Beowulf and his Geats. The bard watched her for a few moments, wondering what she was thinking. He had forgotten that she could smile like that. Why does she stare at him? Why has she not come to me? Has she not seen me in the hall?

Widsith started to cross the hall in her direction, impatiently working his way between mead-benches. Hrothgar saw him.

“Wealth-watcher, Widsith-thane!” The king’s words quieted much of the noise in the hall and a hundred eyes turned to the bard.

Only halfway across the hall, Widsith stopped and bowed to Hrothgar with a graceful flourish. “My honored lord, it seems we have guests from the north.” Forgive me, my true Lord, it’s only an act.

“Indeed we do. They have come to help us in our time of strife.” His voice quavered on the edge of giddiness. To Widsith, he almost sounded senile. Time of strife? Yours is a way of strife, and this fell curse has been a predator upon your doors for too many years.

“I can only wish them great glory from such an honor, lord Hrothgar.” Good. Humble and gracious. Why is she still staring at him?

“You are not a Dane,” Beowulf’s voice was deeper than Widsith had expected. Deeper and more resonant. He would make a good bard.

“I am not, son of Ecgtheow. I am from the south, of Myrging birth.”

The Geat tipped his head slightly to acknowledge Widsith’s acknowledgement. “You speak our tongue very well for a Myrging. But you are a long way from your home among the Angles.”

Home. Only practice and patience kept the bard from wincing. “My home is where my word rests, not my birth. But yes, I am far from the land of the Angles. We both have crossed wide whale-roads to get here.” He paused for a moment, sifting through gathered information, formulating. “Though I did not swim the silvery waves as you have, brave Beowulf.”

Beowulf’s smile broadened, but it was someone behind the bard who spoke next: “I, too, have heard of this swim. They say that you tried to outmatch the noble Breca. They say that he beat you, that he came ashore first.”

Widsith turned and saw Unferth, one of the young Danes newly-adorned with rings of manhood. The thane had been drinking heavily already. Shut up, boy. This one is stronger than that dead brother of yours. You speak with wine. Even in the suddenly tension-filled hall, Widsith felt his thoughts flowing into natural verse.

He þa scylde ne wat

fæþe gefremede, feoþ his betran

eorl fore æfstum…

“But you have heard wrong, Ecglaf’s son,” Beowulf was saying. “It was I who bested Breca in our contest. Together we made the match, together we swam out to sea to fight the beasts of the deep and to test our strength against each other. We wore our armor, and each carried a sword to fend off the sea-beasts. He who stayed out longest was the victor, and Breca had not the strength to combat both wave and serpent. He was driven ashore while I battled the beasts and sent their leavings to the depths. Only when I was certain that Breca had lost did I allow myself to come ashore.”

Unferth whispered something to one of his companions, jogging his elbows. The other man began to feign swimming motions with his arms and the young Danes erupted in laughter.

Beowulf raised his voice to be heard above the din, his eyes narrowing into a cold stare. “And you, Unferth, what have you done for your honor? Where is the older brother to speak of your deeds?”

Even drunk, Unferth recoiled as if he had been slapped. “My brother,” he hissed, “is among the gods.”

“By whose hand?”

Widsith blinked, surprised that the Geats would know the mysterious circumstances of the brother’s death. Word carries fast and far in the north. One must never underestimate that fact.

Unferth stood quickly, his cup spilling and running red wine onto the floorboards. His hand lapped at the hilt of his sword like a thirsty wolf on an iced stream. He bared his teeth. “Do not cause me to take the place of the beast tonight, Geat.”

Beowulf let out a small laugh, far from the response Unferth had expected. “If you are so brave, why are we Geats here?”

The table of visitors broke into laughter of their own, not a few of them making snickering comments about Danish manhood.

Unferth flushed hot red with the fire of anger. Widsith could see that alcohol had separated him from reason, boosting both his misplaced valor and his guilty paranoia. “You are an unhonored, unwelcome gold-delver, Geat. You seek the treasure of Heorot, and your boasting will win you nothing but death tonight by one means or another.” As if the point needed to be driven home, Unferth’s fingers flipped the leather hold from his blade.

“Perhaps, son of Ecglaf. All men die. The ravens come for us all.” Widsith could not read Beowulf’s expression. Confidence? Sadness?

“Odin’s ravens will come for you tonight,” Unferth’s fingers were slipping around the grip of his weapon.

Standing between the two men, Widsith felt a cold sweat forming along his arms. A dangerous game. Help me, Lord. He swallowed hard. “The ravens of the one-eyed do come for us all, Beowulf,” he said.

The entrance of a third party confused Unferth for a moment, and he made no move to bare his sword. Beowulf simply raised an eyebrow at the bard.

Widsith felt the sweat forming at his hairline now. He looked to Unferth, trying to appear noncommittal in the argument. “And I think that greed is not confined to any one people, thane. We even have a proverb in my country: draca sceal on hlæwe, frod, frætwum wlanc. It says that the wyrm will remain in his barrow, ancient and proud among his treasures.”

Unferth’s confusion had subsided, and now he glared at the bard as his anger shifted target. He had always resented the honor bestowed on an outsider. “You are not in your country, Myrging,” he spat. “And no one asked your opinion.”

“Enough!” Hrothgar’s fist struck wood. He was old, but he could still impress with perceived power. “You are drunk, Unferth, and I will not have you insult our honored bard. Widsith is a man of honor among us, an outsider whom I have welcomed into my household with ring and kiss and marriage.”

Unferth bowed his head, smiling in feigned dismay that he and his actions were misunderstood. He had meant nothing by them, of course. They were only words in jest, and he himself would welcome a tale from the Myrging bard.

Hrothgar relaxed slightly and raised his hand to Widsith. “Very well. The son of Ecglaf wishes a song, teller-thane. A tale for our guests.”

“A song to the glory of the Danes,” Unferth said pointedly, staring at the Geat.

Widsith bowed, once more aware of his position between the two men. But he tried to push away such thoughts and to feel the voices of past minstrels begin to flow into his mind. He found it hard to ignore the tension in the air and the way that Aethel continued to stare at the Geat, but he had to try. “As you wish, my lords. A tale of Shield son of Sheaf, scourge of many tribes…”

“In your tongue, Myrging,” Beowulf interrupted. He spoke to Widsith, but he was looking very clearly at Unferth.

Widsith could see that Unferth was scowling, trying to keep his temper in check. Beowulf smiled back, his thick arms crossed across his chest. The bard looked to Hrothgar, hoping for guidance out of the impasse.

The king was smiling, too, looking down with a measure of pride at the young Geat. “Perhaps a short tale of Shield and his son, then, a tale in your own tongue, Widsith-thane. Regale us with the music of your language!” He raised his cup once more, this time to his Myrging cousins across the waters. The hall let out a collective sigh and cups clanked over the mead-benches.

Widsith bowed once more, his mind racing through ill-used vocabulary and verse, weaving and translating the words of those who had gone before. Awkward seconds passed while he let the rhythms move into a cadence within his mind. Finally, he spoke, and the words of his tongue flowed like honey in summer-heat.

Widsith did not return to the realm of dreams that night, though he pretended to sleep when Aethel rose in the night and left his side.

Widsith thought for a moment about traveling to the home of the brave Geats. He could cross the sea to the court of Hygelac when this was finished, comfort them with tales of their sons’ bravery in fighting the night-stalker of Heorot. They will need the comfort of tales when this is done. There will be nothing else to go home. The beast leaves only blood.

The bard grew angry as he thought of the Geats, as he thought of Beowulf. His anger troubled him, but although he did not understand it, he could not deny the emotion that rose like heat in his chest. The Geats would die in the night, perhaps bravely, perhaps not, but Widsith would bring no comfort to those they left behind. No, he decided, he would not travel to the land of the Geats. He would not sing of Beowulf.

He would go away, then, go to the court of the Franks, to the Huns, to the Burgundians, to the distant Langobards. In time, he might see the glories of Rome, though he would, of course, keep his faith a secret. He had heard tales of how Rome treated those it viewed as incorrect in their beliefs. He had heard much during his travels, and the chance to hear more excited him. Perhaps he would learn a tale of Ravenna, or of far-away Persia. Perhaps I’ll write tales, too.

He was at last drifting toward sleep, his mind relaxing into thoughts of other times and other places, his throat softly humming songs not yet sung, when the screaming began.

2 thoughts on “Fiction Excerpt: “The Hand That Binds””