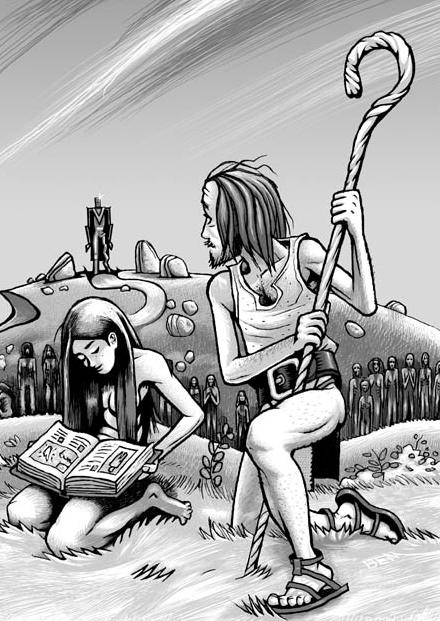

Fiction Excerpt: “Leather Doll”

By Mark Sumner

Illustrated by Bernie Mireault

from Black Gate 7, copyright © 2004 by New Epoch Press. All rights Reserved.

Lisle was a Hereford, bred for leather. She was born out of season, and while the rest of the herd was being starved to loosen up their skins, Lisle was still getting a daily dose of oats and dried berries in hopes of a last minute growth spurt. It made for quite a contrast: the hollow-eyed, haggard, herd, and bright little Lisle with her round limbs and shining hair. Still, if it hadn’t been for the whistling, she would have gone straight to the slaughterhouse with the rest of the twelve year-olds.

Lisle was a Hereford, bred for leather. She was born out of season, and while the rest of the herd was being starved to loosen up their skins, Lisle was still getting a daily dose of oats and dried berries in hopes of a last minute growth spurt. It made for quite a contrast: the hollow-eyed, haggard, herd, and bright little Lisle with her round limbs and shining hair. Still, if it hadn’t been for the whistling, she would have gone straight to the slaughterhouse with the rest of the twelve year-olds.

Meyer was drowsing on his cot in the miserable sod-block line house when he first heard the whistling. His dreams that fall morning were of a town girl, and of what she had done for Meyer the last time he brought in a token, and of grand new pleasures she would surely introduce when she saw the bounty his summer’s work had earned. It was the best dream Meyer had conjured in a month, and he was reluctant to let it go, but the whistling lopped off the sweaty dream like the cold blade of a sickle parted the winter wheat.

Still thick with sleep, Meyer fell from his damp, lumpy bed, stumbled to his feet, and staggered about the soddy in a panic, scattering his few possessions, and bumping his head against the low-hanging roof. By the time he located the precious set of metal tongs among the chaos, Meyer had worked himself into such a lather that he hardly knew what to think. With trembling hands, he gripped the cold handles of the tools and stumbled from the shack to meet his doom.

A small portion of his mind argued for calm. After all, the whistling didn’t sound like any of the redgrass creatures Meyer had tangled with in the past. But that little calm voice was swallowed up by a roar of panic. There were surely many more things in the redgrass than the few pitiful creatures Meyer had crossed paths with — a whole world of things, if the proctors were to be believed. There were the long-bodied crawlers with a multitude of needles for legs, and the little round flyers with jaws the size of their whole bodies, and the armored borers that could appear from under the earth even with no red grass in sight. So far as Meyer knew, not one of them was friendly.

The cattle looked at Meyer with scant curiosity as he hurried up the muddy slopes of the low pasture. A few of them gave agitated grunts and moved away from the ranch hand, most didn’t budge. There had been several false alarms lately, and the herd was used to their inexperienced keeper running wildly about the fields. Besides, with their feed cut back to a quarter normal, they didn’t have the spare energy to go starting at nothing. It would have taken a considerable ruckus to get them interested for more than a moment.

Meyer dashed past the empty food troughs, swerved around the stern clay figure of Proctor Jory, and jumped over a dark-haired cow that lay sleeping in the grass. In the spindly shadow of the windmill he stopped to catch his breath and to listen. For a hopeful moment, he heard nothing but the soft rattle of the bones and cords that made up the windmill’s arms. He could almost believe that the whistling was nothing but a part of his dream — a particularly unpleasant part. Then the sound came again — a light, rippling, warbling series of notes that went up and down in pairs and triplets.

Meyer swallowed hard. Old Applegarten, the owner of the ranch, had said there were flyers bigger than a man’s hand and crawlers half again larger. If such monsters really did exist, then even Meyer’s pair of hard metal tongs would not be enough to hold them. And even if Applegarten had exaggerated, the small creatures were bad enough — the Westhaus Ranch had lost an entire herd to a thing no bigger than an eyelash. Only the proctors knew what sorts of things might lie outside the tame lands. Once the redgrass began, only the proctors could walk through the stalks and still live.

With a final deep breath to build his resolve, Meyer started toward the line of scarlet that edged the pasture, but before he had covered half the distance to the redgrass, it became clear that the whistling was not coming from the edge of the fields. The sound was nearer — much nearer. Whatever was making the noise had moved away from the redgrass and wandered far into the pasture. Meyer shivered. Already half the herd might be lying dead in the high grass.

With his heart beating in his throat and sweat running into his thin beard, Meyer advanced into a patch of mixed barley and wheat. The hungry cattle had already nibbled most of the grass heads from the crops, but the tan stalks alone were still thick enough to hide the source of the strange, frightening sound. Every careful step through the waist-high grass brought the whistling closer, and with every step Meyer expected to see the horrible form of some deadly creature – all poison spines and gnashing teeth — or the bloated, purpled bodies of poisoned cattle. His grip on the tongs grew so tight that his hands cramped and tremors ran up his arms to the shoulders.

Then, when he was near to screaming from the tension, Meyer at last came upon something in the grass. But instead of the articulated horror he had expected, he saw a bare grass-stained foot, then a tan leg, then the freckled curve of a rounded buttock.

Lisle was lying face down in the brown stalks with her chin propped on her hands and her feet kicking in the air. A few loose grains of barley had fallen across her arched back, and stalks of wheat were tangled in her wild brown curls. Her eyes were shut, an expression of concentration locked on her small features. Her lips were pursed and her cheeks were sucked in at the sides. She was whistling.

At that moment, Meyer’s immediate duty was to beat the young Hereford. The rules were very simple — cattle were to be silent. A few moans or cries were to be expected when an animal was in pain, or hungry, or mating, but any cow or steer that went beyond the most basic of sounds was to be severely punished. This was the first rule that Meyer had been taught in school and he had used his club to enforce this rule many times. For those few cattle who persisted in being noisy, he had not hesitated to bring out the redgrass prod. One of the steers bore so many scars that his hide would be nearly worthless at market. Lisle’s whistling certainly deserved the harshest punishment Meyer could deliver.

But instead of striking the little heifer, Meyer only stood over her, listening to the wavering notes and watching her stained feet kick through the air. It was certainly not the first time he had noticed Lisle. She had been a pretty little animal right from the start, with big brown eyes and thick chestnut hair that the blue-white sun had bleached pale at the ends. Very unusual for the breed.

Meyer had thought it a shame that Lisle had been judged too narrow-hipped for breeding. Since arriving at the farm, he had admired Lisle in the fields many times. Watching her was one of the few pleasures in this desolate, isolated patch at the edge of third circle. If fact, though he would never have admitted it, Meyer had even wondered what Lisle would look like if she were cleaned up and put into a dress like a human girl.

It wasn’t exactly an original thought. Back in school, he and his mates had giggled over the idea of putting a cow in woman’s clothing. They even talked of cleaning up a sleek young heifer and bringing her to the Founder’s Dance — strolling her past the elders and past the proctors themselves and leaving before anyone caught on. It would have been a fine prank. But none of them had actually gone through with the jest. Not when everyone understood that such behavior merited hard flogging in the central square of Crash. Or worse.

Meyer’s gaze traced the curve of Lisle’s hips and up the arc of her back to her bare, freckled shoulders. The human girls he knew had very pale skin. Of course, all the human girls he had known were town girls. The job of the town girls kept them inside much of the time. Meyer wondered if it was different for other women, if they had tanned, freckled skin like this little cow.

Lisle abruptly stopped her whistling. Her eyes fluttered, then widened in fear. With a sharp hiss of indrawn breath, she flipped herself onto her back and stared up at Meyer.

A flush of heat washed over Meyer’s face. He felt momentary guilt for the thoughts he was having about Lisle. Then he felt a fresh wash of embarrassment just at the idea that he had allowed himself to become embarrassed in front of a heifer. She was, after all, only an animal. She couldn’t possibly know what he was thinking.

Meyer took a step back, stumbled in the thick grass, and nearly fell. The precious metal tongs dropped from his fingers and landed among the brown stalks. Meyer reached for the tool, slipped again, and went to one knee. Gripped by a near panic that he could not begin to explain, he searched among the barley. Finally, he managed to grasp the handle of the tongs and dragged them back from the grass.

Throughout this display of clumsiness, Lisle lay face up in the field with her mouth frozen in a circle of surprise and her gaze locked on Meyer’s face. If Meyer hadn’t known better, he would have thought Lisle was about to laugh.

The panic drained from Meyer and he smiled back at her. Lisle’s eyes were brown, not green or blue like most real girls’, but there was a brightness in them, an intensity that Meyer had never noticed in any other member of the herd. For the second time in as many minutes, Meyer broke the rules. “It’s all right,” he said. “I didn’t mean to scare you.”

At the sound of his voice, Lisle cocked her head to the side. Her sun-streaked hair spilled over one bare shoulder and her eyebrows rose on her freckled forehead.

Meyer wondered if she had ever heard a voice before. Likely enough, she had not. Not speaking in the presence of cattle was the second rule taught to farm hands. Breaking this rule was punishable by both torture and fine. It was a stricture so drilled into school children that even the youngest would cease any conversation whenever the herds were near.

A mixture of feelings swirled through Meyer. He knew what he had just done was wrong, and he did feel an awful, stomach-tightening wash of guilt, but at the same time he felt an exhilarating sense of recklessness. There were no other human beings around to hear him — no humans within a two-hour walk. For once in his life — for the first time in his life — he was free of the presence of parents, teachers, elders or proctors.

There was a new heat rising along his skin, a heat that had nothing to do with embarrassment or fear. Dressing up the cattle to look like women wasn’t the only thing they had joked about back in school. Watching Lisle in the fields had given Meyer plenty of other thoughts. The prostitute back in Crash might be a real girl, and Lisle only an animal with the same shape, but Crash was four day’s walk down the Axis Road. Lisle was right in front of him.

“Here,” said Meyer. He reached out his hand to the young heifer.

Lisle only looked at his outstretched fingers for a moment, then slowly she brought her hand up to meet Meyer’s. Unlike many ranch owners, Mr. Applegarten didn’t believe in cutting the fingers from his cattle. Meyer was glad for that. Not just because it made caring for the cattle easier, but because in that moment the touch of her fingers made it easier to pretend that Lisle was more than a beast.

Meyer gripped Lisle’s hand firmly and pulled the little cow to her feet. “Come along,” he said. “We’re going to have fun.”

4 thoughts on “Fiction Excerpt: “Leather Doll””