The Shock of the Old: The Professor Jameson Space Adventures by Neil R. Jones

Few things are more exciting than finding an unheralded new author or reading an impressive new book fresh off the press. It is exhilarating to be present at the advent of a significant new work, to witness the beginning of an important writer’s career, or to feel yourself at the cutting edge of a genre. That sense of exploration and discovery is at the very heart of science fiction and fantasy.

Few things are more exciting than finding an unheralded new author or reading an impressive new book fresh off the press. It is exhilarating to be present at the advent of a significant new work, to witness the beginning of an important writer’s career, or to feel yourself at the cutting edge of a genre. That sense of exploration and discovery is at the very heart of science fiction and fantasy.

These genres we love have roots that reach deep into the past, though, some of those roots extending into the cheap pulp magazines of the 20’s and 30’s, venues that at the time — and for long after — were utterly disreputable; anything that had even a whiff of such seamy origins was utterly damned in the eyes of critics.

Today’s top writers have moved far beyond those simple beginnings, and their finest works exhibit a thematic sophistication and literary polish that their progenitors can’t match, even as the best of those pioneers have finally achieved a hard-won respectability (penny-a-word pulpsters like Leigh Brackett and H.P. Lovecraft escaping the lurid confines of Planet Stories and Weird Tales to appear between the staid covers of the Library of America?! It’s about time.)

Writers like Neil Gaiman, China Meiville, and Susanna Clarke are expanding the boundaries of what can be accomplished with what is decreasingly called genre fiction, and for that we should all be grateful. Sometimes though, I must confess that I am compelled to put aside the careful work of the current generation for a while, because I just need a jolt of unadulterated pulp, and nothing else will do. (I don’t know about you, but I wasn’t around for the pulps, much as I wish I had been, so I have to rely on paperbacks, most of which are themselves now as old as I am, or older.)

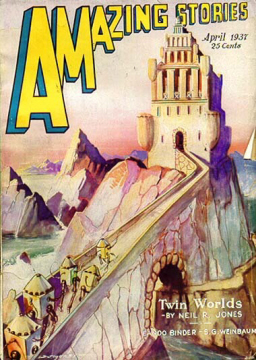

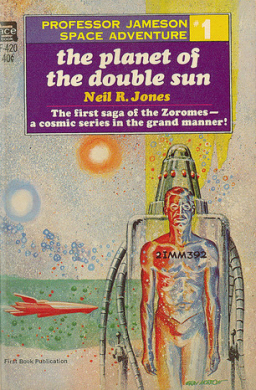

To that end, I recently rocketed my way through a vintage paperback I picked up several months ago, The Planet of the Double Sun by Neil R. Jones. Published by Ace in 1967, the book collects three linked stories that first appeared in Amazing Stories in 1931. These stories formed the beginning of the series for which Jones was most well known, the Professor Jameson sequence, about which a breathless blurb writer at Ace proclaimed:

To that end, I recently rocketed my way through a vintage paperback I picked up several months ago, The Planet of the Double Sun by Neil R. Jones. Published by Ace in 1967, the book collects three linked stories that first appeared in Amazing Stories in 1931. These stories formed the beginning of the series for which Jones was most well known, the Professor Jameson sequence, about which a breathless blurb writer at Ace proclaimed:

Truly, it can be stated that the Jameson series of Neil R. Jones has been the longest running continuous adventure series in the history of science-fiction, never failing to hold the attention and enthusiasm of readers.

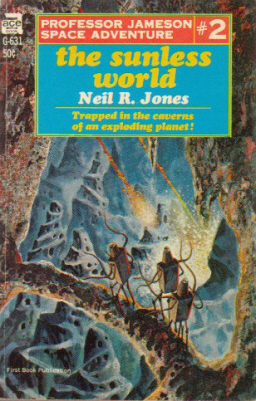

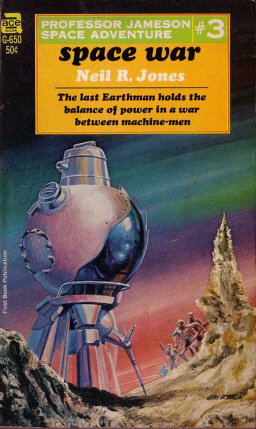

As the last Jameson tale appeared in Astro-Adventures in 1987 (the year before Jones’ death), we have here that rarest of phenomena — a true statement on the back of a paperback (except maybe for that “never failing” part). Ace subsequently published four more collections of Jameson stories that had appeared during the 30’s, mostly in Amazing; several more stories from the 40’s and 50’s still remain uncollected.

The first story in the series, “The Jameson Satellite,” kicks things into high gear (or cleaves the aether, as they said in those days) with little time wasted. The great scientist Professor Jameson, for reasons never adequately explained (because really, what in the world would explain it, except for insane egomania), directs that upon his death, his body shall be placed in a rocket and shot into earth orbit, there to circle the planet forever.

His directions are followed (by his nephew, naturally, probably after cleaning out uncle’s silverware drawer and bank account) and 40,000,000 years later, long after the extinction of the human race, the rocket is retrieved by the machine men of the planet Zor — living brains encased in imperishable robotic bodies, creatures utterly without irony, who look like ambulatory packing crates and all have names like 4C-971 and 25X-987; they were just passing by, more or less.

With their super-science (all machine-men from distant planets possess super-science, but I’m sure you knew that), they revive the professor and put his brain into an extra body they happened to have lying around… and give him a new name, 21MM392, because, you know, calling a six-tentacled, gleaming metal machine-man “Professor Jameson” would just be silly. (Later an alien race with fellows named Snrpd and Brlx and Frlst turns up. This book must have been a typesetter’s nightmare.)

With their super-science (all machine-men from distant planets possess super-science, but I’m sure you knew that), they revive the professor and put his brain into an extra body they happened to have lying around… and give him a new name, 21MM392, because, you know, calling a six-tentacled, gleaming metal machine-man “Professor Jameson” would just be silly. (Later an alien race with fellows named Snrpd and Brlx and Frlst turns up. This book must have been a typesetter’s nightmare.)

Jameson is now a full-fledged Zorome, and ready to cruise the universe with his new-found friends, in search of adventure – which he proceeds to do. (Why didn’t Jameson’s body rot away to literally nothing after all those millions of years? I don’t know and neither does Jones — he employs psuedo-scientific gobbeldygook to double talk past the point with an adroitness that would make Stan Lee blush with envy. And anyway, what does it matter? The whole point is to get that brain into the box!)

In the other two yarns in this first Jameson collection, the professor and his rust-resistant comrades visit the titular “Planet of the Double Sun” and are ambushed by the denizens of a hostile parallel dimension. The Zoromes, in their unrelenting quest for knowledge, ignore Jameson’s warnings and are wiped out by the creatures of the other dimension, who hypnotically induce the machine-men to destroy themselves in an orgy of murder-suicide.

(How do you kill a practically immortal machine-man? Like most such problems, it can all be traced back to a flaw in the original design. You take the most vital part — the brain — and instead of giving it maximum protection by placing it in the middle of the metal body, you cavalierly stick it in a vulnerable dome mounted on top, where it can easily be gotten to by anyone who takes it into their head to smash it, and who can lay their tentacles on a hefty iron bar, an implement with which the Zorome ship is very well stocked. That’s how. Super-scientific immortal machine-men my foot.)

One by one Jameson’s compatriots perish (the tragic last moments of 149Z-24 really raised a lump in my throat, let me tell you); the professor only manages to survive because his human brain is naturally a bit different from those of his friends, and is immune to the malign influences of their enemies… and also because he’s willing to swing an iron bar and shove Zoromes out of the doors of speeding spacecraft with the best of them. (It was him or them, after all. You don’t get to be 40,000,000 years old without knowing how to take care of yourself.) At the end of this middle story, Professor Jameson is stranded on the Zoromes’ disabled spaceship, locked into orbit around the dual star system.

One by one Jameson’s compatriots perish (the tragic last moments of 149Z-24 really raised a lump in my throat, let me tell you); the professor only manages to survive because his human brain is naturally a bit different from those of his friends, and is immune to the malign influences of their enemies… and also because he’s willing to swing an iron bar and shove Zoromes out of the doors of speeding spacecraft with the best of them. (It was him or them, after all. You don’t get to be 40,000,000 years old without knowing how to take care of yourself.) At the end of this middle story, Professor Jameson is stranded on the Zoromes’ disabled spaceship, locked into orbit around the dual star system.

The third story, “The Return of the Tripeds,” picks up where the second one left off. After four hundred years, alone without even a deck of cards, the professor is rescued from his orbiting prison by a tripedal race from another planet of the system. (These are the chaps named Snrpd and Brlx and Frlst. The delightful names make this whole section sort of like a Russian novel – In Spaaaaace!)

Jameson accompanies the tripeds down to the ill-omened planet where the Zoromes were destroyed, and where, generations before, spacefaring triped colonists were massacred by the other-dimensional beasties. The professor helps the tripeds muscle their way into the other dimension to give the baddies a taste of their own medicine; such is their success, the tripeds happily plan to depopulate the other dimension as a prelude to colonizing the whole planet.

In addition to lending his aid to three-legged imperialism, Jameson also fortuitously discovers a bunch of Zoromes who survived the first expedition; they’ve been hiding at the bottom of the ocean for four centuries and are just in need of a little refurbishment. The story ends with our hero and a couple of dozen Zoromes ready to resume their exploration of the universe on their now-repaired ship.

Leaving their tripedal friends to commence their interdimensional genocide, the upgraded earthman and the Zoromes speed “rapidly toward the far-off stars and new adventures.” Not bad for a professor who doesn’t have a department chair or even a parking space anymore.

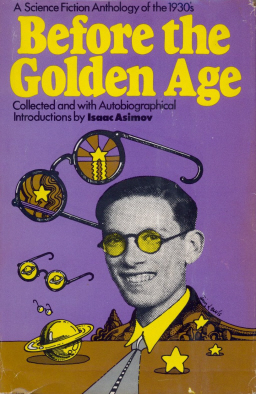

These stories from the dawn of modern science fiction (or from Before the Golden Age, as Isaac Asimov titled his great anthology of these 1930’s tales, and where one of the Jameson stories is reprinted) are a special taste — the plots are clunky and repetitive, the characterization is wooden, where the science isn’t simply outdated, it’s absurd, the prose reads like it was composed by a ten-thumbed alien… and I love every page.

These stories from the dawn of modern science fiction (or from Before the Golden Age, as Isaac Asimov titled his great anthology of these 1930’s tales, and where one of the Jameson stories is reprinted) are a special taste — the plots are clunky and repetitive, the characterization is wooden, where the science isn’t simply outdated, it’s absurd, the prose reads like it was composed by a ten-thumbed alien… and I love every page.

Why? Why read these musty, dusty, clumsily written narratives filled with obsolete science and outdated social notions and unbelievable characters and risable dialogue, when work is being produced today that makes these stories look as crude as cave paintings?

Aside from purely historical interest (Asimov said that the Zoromes gave his eleven year old self the germ of the idea that would eventually become his positronic robots), what have they got that can’t be found in the infinitely more skillful and nuanced fiction of today?

Perhaps it has something to do with their very age. Almost anything is more impressive when it is done for the first time and, goofy as these stories are, they have some of the vigor and freshness about them that comes from something being done for the very first time. You admittedly have to make some allowances and put yourself in the right frame of mind, but if you do, you can still read the Jameson stories and other science fiction of those early days and see them reflecting the light of the genre’s first sunrise, so to speak.

Neil R. Jones and the other SF writers of his era were true pioneers of the imagination, and what they lacked in finesse they made up for in vision. They weren’t following a trail already blazed and adding their own improvements; they were imagining situations that were literally new, and they were thinking through problems that no one had ever solved because no one had considered them before.

The solutions (both scientific and literary) that these early writers offer are often — maybe even usually — ridiculous, but they have the virtues of audacity and originality; they filled a vacuum that no one even realized was there until something was tossed into it. In this context, the reference I made earlier to cave paintings is apt.

I came across a quote once, somewhere, to the effect that the first cavedweller who realized that lines on a wall could represent humans and beasts, surpassed in sheer, blinding genius all the other artists who have ever come after. I think of the writers who built science fiction, slaving away at their manual typewriters for wretched word rates, like that — acting on possibilities that only they could see, and then making others see them too.

Sheer, blinding genius is not a term that will ever be applied to Neil R. Jones, or E.E. “Doc” Smith, or Edmond Hamilton, or Ray Cummings, or Jack Williamson. But they were bold and brave, and they jumped into the void where no one had been before. If we’re willing to follow their sometimes clumsy explorations and jump with them, then even at this late date we can still catch some of the excitement and optimism and wonder that they carried with them.

Through these creaky old stories, you can journey to places no one had ever visited, and might even return appreciating what we have now a little bit more.

See all of our recent pulp articles here, and read “Zoromes Make the Happiest Cyborgs,” Douglas Draa’s review of The Professor Jameson Space Adventures, here.

I don’t have a lot of the old science fiction paperbacks from my youth but I do own the five Ace books of Professor Jameson. I totally agree with the magic of those long ago tales much like Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers being so awesome because they were new and visionary and breathed life and joy. Over the years as a casual collector of pulps (comics tend to be the priority for me) I have bene able to get four Amazing Stories (ul 31–the ast appearance, Feb 32, apr 36, Apr 37) and one Super Science Stories (Sep 50–second to last published appearance before that 1987 Astro-Adeventures that I have never seen. My dealer thought it was silly buying them when I already HAD the paperbacks but he also didn’t charge an arm and a leg either. With Doc Smith reprinted very 20 years or so I have been a bit disappointed the Jamesons have never been finished up or given another shot. Just imagining the cover art alone whets the appetite.

For pure whimsy I logged into You Tube and typed Professor Jameson and was startled to find a video where two characters -one clearly a Zorome are dancing away under MMD] Professor Jameson and Robo-Miku on asteroid [Cyber Thunder Cider] –Enjoy. I posted a comment under my real name-forgetting I don’t use an alias there but no harm no foul.

[…] Read “The Shock of the Old,” Thomas Parker’s review of The Professor Jameson Space Adventures, here. […]

On my way to Youtube! Thanks!

Not 10 minutes ago, I went into my basement to search through some of my Ace pbs, looking for something fairly short to get me through the rest of the evening, and I brought up the first two Professor Jameson books, neither of which I’ve ever read. I also have not visited the Black Gate site for over three weeks (too busy getting ready to begin another semester of teaching college English) — and was thrilled to backtrack a little and find this article on Neil Jones. Coincidence? I think not…

[…] Gernsback Awards, Volume One The Professor Jameson Space Adventures by Neil R. Jones See a 1942 Pulp Magazine Rack in All Its Glory The Original Bug-Eyed Monster: Astounding Stories, […]

[…] but it’s ruined mainly by the dreadful prose. Neil R. Jones was once somewhat famous for his Professor Jameson stories – I haven’t read any of those, were they this […]